Anthony Chesebro

Stony Brook, New York, United States

“There is only one season, the season of sorrow.”1

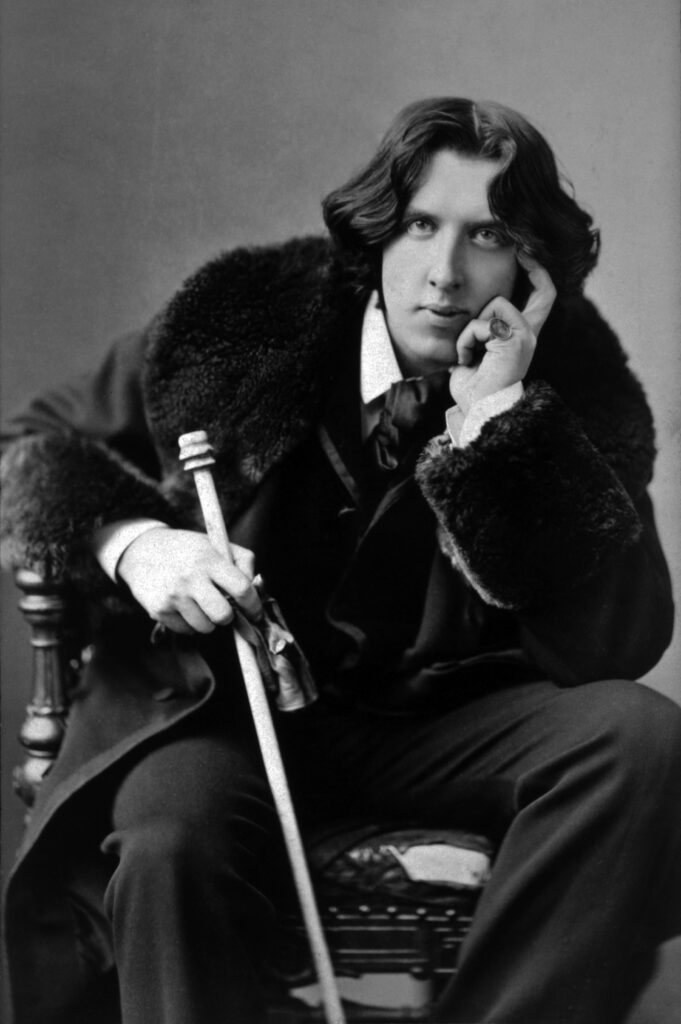

Imprisoned for a relationship that was criminalized by the government of his time, in 1897 Oscar Wilde had spent two years in jail. Finally granted permission to write, over a period of three months he produced De Profundis, an eclectic document that ranges from a narrative of his imprisonment to philosophical discourse. Perhaps most striking is how the letter serves as a prose rhapsody on the nature of mental anguish – an individual reflection on the intersection of physical and psychological suffering. As “a man who stood in symbolic relations to the art and culture of [his] age,”2 Wilde could not allow his mental trials to pass without seeking a new self from the ashes of his grief.

Though much of De Profundis is a reflection on his life before prison, Wilde weaves in commentary on his mental suffering in being separated from all he held dear. His narration parallels, in many ways, the story of one experiencing an illness: forces beyond his control have isolated him and preyed upon his body and mind. The narration of illness, or indeed any embodied experience, is more than a journal. It is an externalization of ideas, an interpretation of the narrator’s lived experiences.3 Wilde himself viewed his work through this lens, writing of his suffering as “a fresh mode of self-realisation.”4 His account offers a unique point of view from which to probe the depths of mental suffering.

The problem of life

“And if life be, as it surely is, a problem to me, I am no less a problem to life.”5

Wilde grappled6 with the question of his own frailty and suffering with a mind capable of conceptualizing eternity while experiencing an interminably slow temporality. In this tension between now and forever, he found isolation and contemplation, turning these into the tools by which he understood his suffering. Here he found silence – a quietude that brought with it abundant reflection. As Woods put it,7 in the suffering narrative, it is frequently within silence that one can be open to randomness, while also finding intensity and ecstasy. In this crystallization of the sorrowful experience, the mind becomes capable of synthesizing a new realization of its own suffering, a fresh understanding of its feelings. Wilde felt that “there is about sorrow an intense, an extraordinary reality”8 that can ground the mind in its own experience and help it grow in self-reflection.

Prolonged and profound mental distress, however, can be a draining and damaging experience. Wilde phrased it not as heartbreak, but as a heart that turns to stone in an attempt to inure it to more suffering.9 The listlessness, apathy, withdrawal, and incessant pain of mental suffering can lead to stagnation of mind and body. When physicians seek to understand their patients’ suffering, narrative can be a powerful approach. As Rita Charon has written, narratives such as Wilde’s contribute immensely to the medical field by giving “the means to probe, honor, represent, and live in the face of temporality, singularity, intersubjectivity, causality/contingency, and ethicality.”10

By narrating the journey through mental pain in vivid detail, Wilde has allowed us to journey with him through these sorrows, through the pain and misery that shaped his lived experience. Through his writing, he has given us a new lens through which to understand our own pain and to empathize more deeply with others. As Charon describes it, this is to stand on the precipice of an illness,11 to catch a glimpse of the experience of suffering for ourselves, so we can best mirror that suffering in others. There may be “pain and terror and horror involved”12 in facing suffering for ourselves, but we can use this to reach a new understanding of the human condition. Aesthetic works,13 like those Wilde aspired to create,14 do not purge feelings from the writer but crystallize experiences into tangible, discernable forms that can be more easily analyzed, interpreted, and understood.

The transit of the self

“I must get far more out of myself than ever I got, and ask far less of the world.”15

The exposure to mental suffering creates an environment of strain intolerable to the temperament,16 as Wilde would put it, that recasts the mind in a mold inured to new assaults. Charon describes17 the mental experience of illness as encompassing two uncompromising aspects: the necessity of the self to travel away from its former self, and an impossibility of returning to the state it once inhabited. Suffering is a journey, often unexpected, always painful – yet one that can lead to a novel growth of self not found in other conditions.18 This transformation, while integral to understanding mental suffering, can pose a challenge in narrating its course. As Kokanović and Flore point out, it is these “fraught, partial, unfinished and unfolding materialities of human bodies”19 that make an understanding and narrative of the transition from self to self so difficult.

It is in seeking to understand the lived experience of suffering that the utility of studying narratives shines. The narrative experience connects the mindfulness of one person with the suffering of another.20 To listen to the story of another person’s journey is to begin to understand their waking, breathing reality. In the formation of a narrative, there is a simultaneity21 of truth and construction: as suffering alters the former truth to create a new one, this shift in morphology can be expressed best in narrative form. This shifting is internal to the sufferer and leads, as Wilde discovered, to a secret within the self.22

Gazing upon the face of sorrow

“Or else he sat with those who watched

His anguish night and day;

Who watched him when he rose to weep,

And when he crouched to pray.”23

In the end, our observation of suffering, if it is to be a meaningful interaction, cannot be a passive, sanitized, empty arrangement. It must be an active comprehension, an energetic standing together with the person who suffers. This requires the admission of our own frailty and suffering, an acceptance that such a state is not divorced from our own reality, but one that has been and will be ours again. Through this empathic ability, we work towards becoming the ideal caregiver described by Wilde: at once “a suggestion of what one might become as well as a real help towards becoming it.”24

In the course of giving and receiving accounts of illness, and exploring the depths of mental suffering, we aspire to the aesthetic ideal of seeing that “beauty and sorrow walk hand in hand, and have the same message.”25 Though there is pain, dismay, hurt, longing, and denial, the journey need not be fruitless nor devoid of beauty. As we seek to more fully empathize with others, we also better understand ourselves.

End notes

- Oscar Wilde, “De Profundis,” in Collins Complete Works of Oscar Wilde Centenary Edition, ed. Owen Dudley Edwards, Terence Brown, Declan Kiberd, and Merlin Holland (Glasgow: HarperCollins, 1999), 1010.

- ibid, 1017.

- Renata Kokanović and Jacinthe Flore, “Subjectivity and Illness Narratives.” Subjectivity 10, no. 4 (2017):329–339, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41286-017-0038-6.

- Wilde, “De Profundis,” 1018.

- ibid, 1022.

- “We think in Eternity, but we move slowly in Time.” Wilde, “De Profundis,” 1025.

- Angela Woods, “Beyond the Wounded Storyteller: Rethinking Narrativity, Illness and Embodied Self-Experience,” in Health, Illness and Disease: Philosophical Essays, ed. Havi Carel and Rachel Cooper, 113–128. (London: Routledge, 2014), 126.

- Wilde, “De Profundis,” 1024.

- ibid, 1025.

- Rita Charon, “The Ethicality of Narrative Medicine,” in Narrative Research in Health and Illness, ed. Brian Hurwitz, Trisha Greenhalgh, and Vieda Skultans. (Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2004), 29.

- Rita Charon, “The Ecstatic Witness,” in Clinical Ethics and the Necessity of Stories, ed. Osborne P. Wiggins and Annette C. Allen. (Berlin: Springer, 2011).

- ibid, 178.

- See ibid, 177.

- Wilde himself in another essay makes even stronger claims about the importance of these approaches, laying out a fascinating argument that art, and in particular a critical approach to aesthetics, is essential to philosophical inquiry. See Oscar Wilde, “The Critic as Artist,” in Collins, 1108-1155.

- Wilde, “De Profundis,” 1041.

- ibid, 1052.

- Charon, “Ecstatic Witness,” 165.

- Wilde took this argument even further, opining that sorrow is “the supreme emotion of which man is capable.” He also gave a glimpse into his mind, stating: “there are times when sorrow seems to me to be the only truth.” (see “De Profundis,” 1024 for both quotes).

- Kokanović and Flore, “Subjectivity.”

- Lewis, Bradley, “Mindfulness, Mysticism, and Narrative Medicine.” Journal of Medical Humanities 37, no. 4 (2016): 401–417, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-016-9387-3.

- Lewis describes them as “co-constitutive” in narrative medicine (ibid).

- Wilde, “De Profundis,” 1020.

- Wilde, “The Ballad of Reading Gaol,” in Collins, 887. This poem, while not part of De Profundis, was written as a reflection on Wilde’s time in prison, and thus the works are intimately tied together, as they share this common origin.

- Wilde, “De Profundis,” 1025.

- ibid, 1025.

- ibid, 1059.

References

- Charon, Rita, “The Ecstatic Witness,” in Clinical Ethics and the Necessity of Stories, edited by Osborne P. Wiggins and Annette C. Allen. 165-183. Berlin: Springer, 2011.

- “The Ethicality of Narrative Medicine,” in Narrative Research in Health and Illness, edited by Brian Hurwitz, Trisha Greenhalgh, and Vieda Skultans. 21-36. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2004.

- Kokanović, Renata, and Jacinthe Flore, “Subjectivity and Illness Narratives.” Subjectivity 10, no. 4 (2017):329–339, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41286-017-0038-6.

- Lewis, Bradley, “Mindfulness, Mysticism, and Narrative Medicine.” Journal of Medical Humanities 37, no. 4 (2016): 401–417, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-016-9387-3.

- Wilde, Oscar, “De Profundis,” in Collins Complete Works of Oscar Wilde Centenary Edition, edited by Owen Dudley Edwards, Terence Brown, Declan Kiberd, and Merlin Holland, 980-1059. Glasgow: HarperCollins, 1999.

- “The Ballad of Reading Gaol,” in ibid, 883-899.

- Woods, Angela, “Beyond the Wounded Storyteller: Rethinking Narrativity, Illness and Embodied Self-Experience,” in Health, Illness and Disease: Philosophical Essays, edited by Havi Carel and Rachel Cooper, 113–128. London: Routledge, 2014.

ANTHONY CHESEBRO is a second year MD/PhD Student at the Stony Brook University Renaissance School of Medicine. His research interests lie in theoretical and computational neuroscience, with a focus on neuroimaging and diagnostics. Outside of research, he is interested in the intersection between humanities and medicine, particularly through the lenses of narrative and performativity.

Leave a Reply