Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

“Civilization rests upon two things – the discovery that fermentation produces alcohol, and the voluntary ability to inhibit defecation.”

—Robertson Davies, The Rebel Angels

The life of the peasant in the sixteenth century was hard. There were wars of religion, war taxes, and Spanish troops occupied the Lowlands. Peasants also had the usual concerns of farmers throughout history. The need to feed, clothe, and shelter his family was the highest priority. At the very bottom of the list was the need to find a private, discreet place to relieve himself.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525-1569), the master of sixteenth-century Netherlandish painting, most often painted what he observed around him, rather than biblical events.

“He knew the peasants . . . He saw them as they were, with their defects, their ugliness, their misery, their uncouthness and their courage, their revolt and their patience. He watched them drink, dance, and stuff themselves with food; he watched them vomit and relieve themselves. Bruegel observed, accepted, represented. He appeared crude at times, but he was true; he was never vulgar, dull, ribald or obscene.”1

Of the 120 proverbs illustrated in his superb 1559 painting The Flemish Proverbs, at least seven concern bodily functions in the “more direct language customary in that day and age.”2 We have “Hy kak op de wereld,” meaning “He craps on the world,” or despises it. Kaken was the verb used in sixteenth-century Dutch for “to defecate.”3 There is also “He wipes his behind on the door,” meaning, “He makes light of everything.”

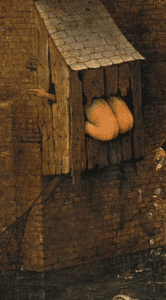

Two inseparable friends are portrayed as two sets of buttocks defecating out of the same window over a canal, thus, “They both crap through one hole.” A clear-cut matter “hangs like a privy over a ditch.” To describe someone as “running as if his backside were on fire,” tells us he is in great distress. A proverb that recurs in Bruegel is “He craps on the gallows,” meaning he is scornful of authority, or is not deterred by any penalty. One of the proverbs concerns urination: “He pisses against the moon,” meaning he attempts the impossible. This proverb is also illustrated in the earlier (1558) Twelve Proverbs: “Ick pisse altyt tegen de maen.”

The figure of “de kakker,” (“the crapper”) appears in several of Bruegel’s works.4 In Superbia, (c.1556), part of his series Seven Capital Sins, one sees a behind, from which excrement issues. The same applies to Luxuria (1557). In The Fair at Hoboken (1559), there are at least two men openly defecating. The depiction of defecation is much more discreet in The Tower of Babel (1563), where de kakker is a tiny figure in the foreground. In The Peasant Dance (c. 1567-1568), we see the back of a man who is facing a wall, maybe discreetly urinating.6

Of the nearly one dozen paintings done in 1568, the year before Bruegel’s death, only one shows de kakker. Before describing that painting (The Magpie on the Gallows), one might ask why the depiction of defecation in his works went from completely obvious, to discreet, to absent. Stewart7 suggests that the upper class, the potential purchasers of Bruegel’s paintings, were part of a shift towards an “increasing sense of decorum in . . . society,” with aspects of human behavior (defecating, for example) becoming more “private” and thought “indecorous” to be shown in artwork. The upper class was already using designated places for relieving themselves.

Bruegel was not hesitant about using his works to express political opinions. The Slaughter of the Innocents, for example, showed the murder of children taking place in Flanders, not in Bethlehem, and the murderers were Spanish troops led by the Duke of Alba, not Herod the Great’s soldiers. The Magpie on the Gallows shows people dancing near a gallows, as well as a man squatting and defecating in a corner of the painting. The expressions “dancing under the gallows,” as well as “to crap at the gallows,” are used to describe someone unafraid of death or authority. The gallows may be taken to represent Spanish “justice,” as applied to the low countries.

The magpie is traditionally associated with gossip, and gossip was dangerous in a country that “hosted” the Papal Inquisitor. It appears, then, that this last painting is a call to resist oppression, even if the gallows awaits.

References

- Bob Claessens and Jeanne Rousseau. Bruegel. New York: Portland House, 1987.

- Rose-Marie Hagen and Rainer Hagen. Bruegel:The Complete Paintings. Köln: Taschen, 2005.

- Denis Ribouillart. “Regurgitating Nature: On a Celebrated Anecdote by Karel van Mander About Pieter Bruegel the Elder,”JHNA,2016.

- Ribouillart, “Anecdote.”

- NA. “Discovered Something Interesting in The Famous Painting ‘The Tower of Babel’ by Bruegel. 2016. Reddit.com.

- Alison Stewart. :Expelling from Top and Bottom: The Changing Role of Scatology in Images of Peasant Festivals from Albrecht Dürer to Pieter Bruegel. 2004.digitalcommons.unl.edu.artfacpub/3.

- Stewart. “Expelling.”

- Hagen. “Complete Paintings.”

HOWARD FISCHER, MD, was a professor of Pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan. He studied medicine at the Catholic University of Louvain, and is fond of Belgium and the Belgians.

Leave a Reply