Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

|

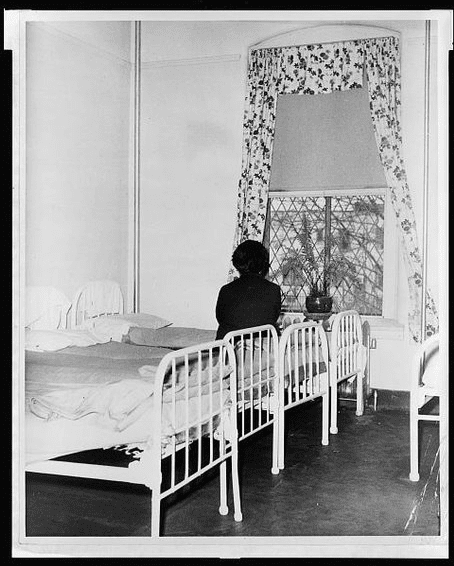

| Crowded bedroom at Brooklyn State Hospital. World Telegram & Sun photo by Dick De Marsico. 1961. Library of Congress. No known copyright restriction. |

Literature and science may complement each other. Sometimes they actually describe the same phenomenon. Gabriel García Márquez (1927–2014) was a Colombian novelist, journalist, and short story writer. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1982. His short story “I Only Came to Use the Phone” (1978), part of the collection Strange Pilgrims (1993),2 describes a nightmarish chain of events.

A twenty-seven-year-old Mexican music hall entertainer, María de la Luz Cervantes, is stranded in the rain after her car breaks down en route to Barcelona. She needs to call her husband to tell him she will be late in joining him for his magic act performances scheduled for the evening. She is picked up by a bus driver with a bus full of sleeping women bound for a psychiatric hospital (a former convent). On arrival María, wrapped in a hospital blanket like the other women, is mistaken for a patient when she goes in to find a phone. She explains her problem but no one believes her. She is assigned a bed and the next day explains her situation to a doctor, but again she is not believed.

Her husband tries to find her but wonders if she has left him as she has done before.

After two months in the hospital, María “starts to join in the life of the cloister.” During a disturbance, María finds herself alone in an office with a phone. She calls her husband, but before she can explain, he calls her “whore” and hangs up. She gets a message sent to him via a matron she has to sleep with. When he comes to get her, the hospital director tells him that María’s condition is “serious.” María describes the horrors and brutality of life in the place and he tells her he will come and see her every week. She responds, “For God’s sake, Baby . . . Don’t tell me you think I’m crazy too!” He comes back the next week but she does not want to see him. She returns the letters he sends. A visitor describes how María is “content with the peace of the cloister.” Later, the hospital is demolished and the fate of María is unknown.

A South American author3 has likened the brutality and authoritarian style of the asylum to Spain under the dictator Francisco Franco, and García Márquez alludes to “Franco” or “the Generalissimo” three times in the story. María just happens to be in “the wrong place [at the] wrong time.” Other critics4 have taken an “existential approach” and call the asylum an allegory of human society, where the demands and policies of society cause one to lose “identity and selfhood.” In this “nightmare of conformity . . . everybody has to be objectified based on social . . . norms.”

The goal of the present article, however, is to show how, in non-symbolic, non-allegorical form, the events in this short story can and do happen. David Rosenhan (1929–2012), a professor of psychology and law at Stanford University, published the results of a revealing experiment in 1973.5 The experiment, which began in 1969, consisted of sending psychiatrically normal volunteer “pseudopatients” to psychiatric hospitals and seeking admission on the basis of a fabricated symptom, often that of hearing voices. Eight undercover pseudopatients gained psychiatric admission. Seven were given a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and one of manic-depressive (now called “bipolar”) disorder. A day after admission, the pseudopatients told the hospital staff that the symptom had disappeared.

Their hospitalizations lasted from seven to fifty-two days, with an average of nineteen days. Hospital staff had no idea that these patients were not authentic, but in one-third of these hospitalizations, other patients suspected they were undercover journalists, researchers, or regulators.

In his 1973 paper, Rosenhan declared that “psychiatry had no reliable way to tell the sane from the insane.” The volunteers, it seemed, were “deemed insane because they were in an insane asylum.” Once again, a case of “wrong place, wrong time,” although this time voluntarily, as part of a research project. The paper, published in Science, had wide-ranging effects, not the least of which was a massive deinstitutionalization of psychiatric patients because of a loss of faith in psychiatry, its practitioners, and its treatment techniques. In 1963 the US had about 500,000 inpatient psychiatric beds, half that number in 1973, half again (about 100,000) in 1983, and 50,000 in 2017.

Cahalan6 suspects that some of Rosenhan’s data were fabricated. She found files (or other evidence) on only three pseudopatients, one of whom was Rosenhan himself. Old records showed that on Rosenhan’s undercover admission, he gave the examiners much more than one symptom. Cahalan does not (and should not) justify “fudging” data, but notes that the 1973 paper showed the shaky foundation of some psychiatric diagnoses and the inflexibility of psychiatric hospital personnel.

The María of García Márquez’s fiction unfortunately had (and may still have) real-life counterparts.

References

- David Rosenhan. “On Being Sane in Insane Places,” Science, 179:250-258,1973.

- Gabriel García Márquez. Strange Pilgrims. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1993.

- Isabel Rodríguez Vergara. “Haunting Demons: Critical Essays on the Works of Gabriel García Márquez. 1998. Portal Digital Library-INTERAMER.

- Shahin Keshavarz and Mohammad-Javad Haj’jari. “I Came Only to Use the Phone” [sic]: Márquez’ Existential Nightmare of Conformity, 2020. researchgate.net/publication/344666834

- Rosenhan, “On Being Sane.”

- Susannah Cahalan. The Great Pretender. Edinburgh: Canongate Books Ltd, 2019.

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D., was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan. He is an admirer of the works of Gabriel García Márquez.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 1 – Winter 2022

Fall 2021 | Sections | Psychiatry & Psychology

Leave a Reply