Ahmed Elhag

Albany County, New York, United States

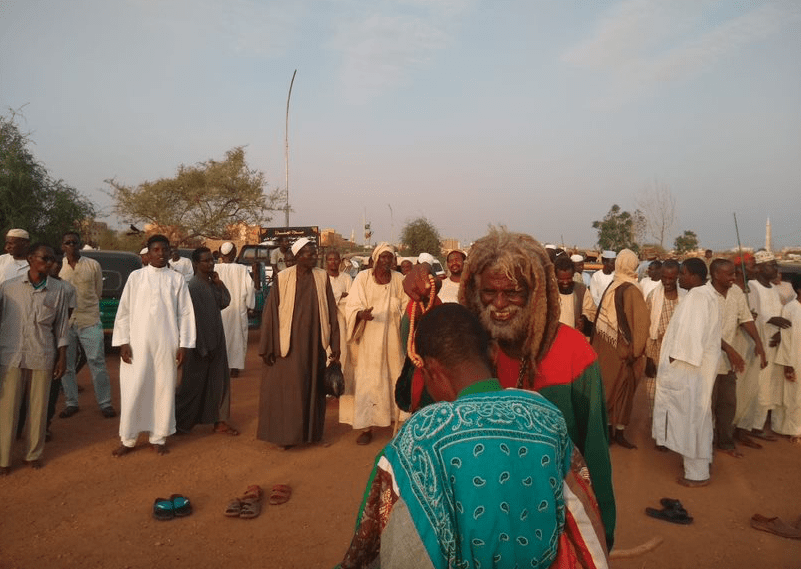

Traditional medicine has been the dominant form of healthcare for much of human history. To many today, traditional medicine has been reduced to an occasional alternative to be used either in addition to or at times in place of conventional care. However, in several rural and secluded areas of my native Sudan, traditional medicine is not an alternative but the only means of treating physical and mental ailments. In 2017, the World Bank reported that estimated number of physicians in Sudan (per 1,000 people) was 0.2618.1 Many of these physicians, however, along with much of the country’s healthcare infrastructure, are concentrated in urban areas, leaving the rural population to depend on non-conventional care. Much of this care comes from holy Sufi saints and their loyal dervishes.2 These holy men often refuse payment and consider the well-being of their communities more than enough compensation. Growing up in Sudan, the most common Sufi healing methods I witnessed were either herbal or spiritual As a Sufi myself, I loved these men for their efforts, but as a healthcare worker, I dream that one day these traditional methods can be complemented by modern medicine.

Sufi herbal treatments

Herbal treatments are often used to treat anything from malaria and cholera to more general symptoms such as inflammation, diarrhea, and bleeding. Common ingredients include sesame oil, ginger, and hibiscus leaves, all mixed into ancient recipes passed on through generations. Although most of these treatments remain clinically untested, many of the ingredients frequently used are known to have some antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties.

Sufi spiritual treatments

The second major form of treatment is spiritual. The simplest form of this would be visiting the tombs of great Sufi saints such as that of Sheikh Hamid Al-Nil in Omdurman. As Sufi Muslims, we believe that visiting these tombs hold great baraka (blessings) and can even bring miracles if one comes with a pure heart. The basis of the baraka is rooted in the Sufi concept of love, and I quote our beloved poet Jalaluddin Rumi:

“The purpose of the dunya (worldly life) is not to find love or search for love, but to break the walls we built around it.”

Many in Sudan hold that the Sufi saints have attained a love for God and his creations so pure that even the impossible may become possible. An example of such a miracle is the story of the sixteenth-century saint Shiekh Dafalla Almosbin and his trusty dervish Jolok. The story states that one-day Jolok went to the Nile River to fill a pot with water for his morning tea, but while doing so was attacked and eaten by a crocodile. When Shiekh Dafalla heard of this tragedy, he ran to the river and called for the crocodile. The crocodile then came forth and Shiekh Dafalla whacked it with his prayer beads, causing the crocodile to turn to stone and allow Jolok to exit safely.

Other spiritual treatments are healing amulets, meditation, and prolonged prayers. Some in the past have asked me if I believe in these spiritual treatments, and to that I say, “Of course, with all my heart.” As Sufis, we are committed to our beliefs, but we also love science. My grandmother, a doctor herself, would always remind us that one must first seek the medical sciences and then after consulting with a medical professional move on to the spiritual sciences.

The future of healthcare in Sudan

With a lot of the current uncertainty in Sudan, it may be difficult to outline what the future may hold. But as a healthcare professional, I dream that one day I can work to establish a holistic healthcare system in Sudan that can fulfill both the medical and spiritual needs of its patients. Healthcare infrastructure must be expanded to reach all areas of Sudan both rural and urban.

As Sufis we are raised to love science, both the spiritual and the physical. Many of our dervishes would be more than happy to undergo training with medical professionals to establish guidelines for combining a traditional component to the healthcare system. As a final note, I would like to reiterate that these traditional healers may not always be right in their treatments, but they struggle to do their best in a country where many of its rural inhabitants have no access to basic care.

End notes

- “Physicians (per 1,000 People) – Sudan.” World Health Organization’s Global Health Workforce Statistics. The World Bank, 2017. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.PHYS.ZS?locations=SD

- A Muslim ascetic devotee of a Sufi order.

AHMED ELHAG is a Sudanese graduate student and community health worker currently specializing in biotechnology and clinical laboratory science. After completing his studies, Ahmed aspires to work on rural development projects in Sudan, particularly within the Nuba Mountains.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 2 – Spring 2022

Leave a Reply