Anand Raja Devaraj Sushama

Kerala, India

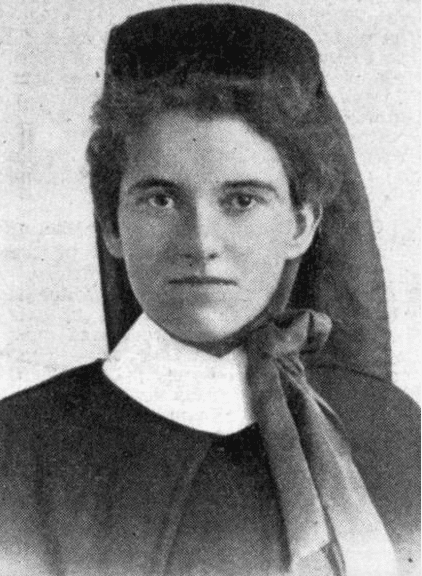

Elizabeth Kenny photographed in 1915. Unknown photographer. Item held by John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

Medical practices flourish and fall out of favor with time. Some become the norm only to turn redundant later; others prevail after a hard battle for acceptance. A campaign is even more arduous when the proponent is outside the establishment. Sister Elizabeth Kenny and her eponymous polio treatment, the “Kenny Regimen,” epitomize this tale of an outsider’s unrelenting duel against the medical establishment.

In the beginning of the twentieth century, the scourge of polio was rampant and had no effective therapy. The orthodox medical treatment at the time was to immobilize affected limbs, which lamentably culminated in crippling. Change, however, was just around the corner.

The torchbearer was an informally trained, uncertified bush nurse from rural Australia. In 1911 during a home visit, Sister Kenny encountered a young girl in constant muscular pain that became worse when touched. The child’s legs were twisted and contracted. Confused by this unfamiliar condition, Kenny wired her mentor Dr. McDonnell for advice. He replied, “Infantile paralysis. No known treatment. Do the best you can with the symptoms presenting themselves.”1 Oblivious to the established practice, she tried applying heated salt in a bag to relax muscle spasms. The child responded and upon awakening from a relaxed sleep, said, “I want them rags that wells my legs!”1 She explored different techniques and subsequently developed a form of physical therapy that aimed to relieve pain and spasms through the use of hot moist packs, early mobilization, and exercise.

News of a child with polio who regained the ability to walk under Kenny’s care spread like wildfire. Amid the Queensland polio epidemic, local people helped her open a rudimentary paralysis treatment facility. Her success in managing the paralyzed gradually led to the establishment of state-funded Kenny Clinics in several Australian cities. However, conservative Australian physicians saw her as an ignorant upstart. As her novel method was not medically sanctioned, physicians did not allow her to nurse acutely ill patients who were under care in “professional hospitals.” Thereby she was left with chronically-afflicted patients—the “medical rejects.”2

Kenny endured years of ridicule from physicians, nurses, and physiotherapists. She later recalled, “I was wholly unprepared for the extraordinary attitude of the medical men in its [sic] readiness to condemn anything that smacked of reform or that ran contrary to approved methods of practice.”1 Dr. McDonnell represented a small minority of physicians who backed her. He claimed, “She has knocked our theories into a cocked hat; but her treatment works, and that’s all that counts.”3

In 1938, the Queensland Royal Commission investigated her treatment method. Contrary to the evidence from case reports, the Commission accused her of wasting public time and money. However, popular support had swelled to a degree that could no longer be ignored by health authorities and the government continued to support her. With the outbreak of World War II, government interest in her method waned. Consequently, she set out to America with a lukewarm recommendation letter from the Government of Queensland. She hoped that American physicians would be more welcoming than their Australian counterparts, drawing on the popular notion of the open-minded American.4,1

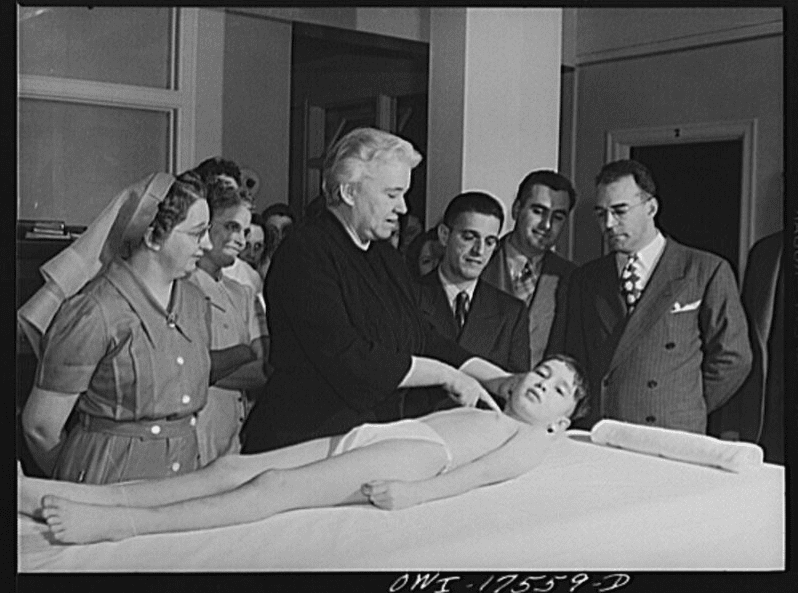

Sister Kenny conducting a class at the Elizabeth Kenny Institute. On her left are Dr. Pedro Gonzales of Havana, Cuba, and Dr. James Vila of San Juan, Puerto Rico. Delano, Jack, 1914-1997, photographer. Farm Security Administration – Office of War Information photograph collection (Library of Congress).

Contrary to her expectations, Kenny had to confront bitter antagonism from medical authorities. In 1940, when Kenny discussed her method with the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (NFIP), some looked bored, some took naps, and one even amused himself by drawing an outline of her features. The man in charge of NFIP, Basil O’Connor, said, “I think she is a crackpot, but I’m not so sure she may not have something.” Kenny had a war of words with Dr. John Coulter’s physiotherapist, who retorted scornfully, “Do you mean to tell me that I have been massaging monkeys for two years for symptoms of a disease that does not exist?”5

Notwithstanding, physicians Miland Knapp and John Pohl who coordinated polio treatment centers in Minneapolis were impressed. Despite the lack of clarity in Kenny’s explanations, her methods assisted paralyzed patients. Rumors about Sister Kenny increased to such a degree that the ward she supervised at Minneapolis City Hospital had a deluge of patients and was forced to explain that no additional rooms were available for treatment.6 This eventually prompted the establishment of the Kenny Institute.

By the mid-1940s, her uneasy alliance with the American Medical Association and NFIP eventually turned into a fierce battle over medical orthodoxy and professional self-interest. The infamous Polio War was invigorated when NFIP denied a research grant to the Kenny Institute. People responded by threatening the NFIP that they would withhold contributions. Kenny had succeeded in stimulating the public to rethink the medical establishment’s claim to a monopoly on scientific truth and medical authority. The stream of medical populism, in which Kenny and her supporters floated, emerged victorious in medical politics.5 Later, Drs. Cole and Knapp published a report in the Journal of American Medical Association endorsing the Kenny Method. Though her explanations were rejected, both the NFIP and the AMA publicly recommended the Kenny Method as superior to the orthodox method of immobilization.2

Extensive media coverage helped Kenny establish an image as a crusader and amass a group of influential allies. Her refusal to accept fees from parents of crippled children was also publicized to her advantage. She implied that her mission was divinely sanctioned by claiming that God was the “doctor” of her mission. With a meteoric rise in popularity, she published her life story with the aid of Martha Ostenso, a novelist. She was the subject of a Hollywood movie titled Sister Kenny, which was later revealed to be brazen propaganda for Kenny’s method. One sociologist later concluded that Kenny’s attributes and activities were similar to those of cult leaders.7

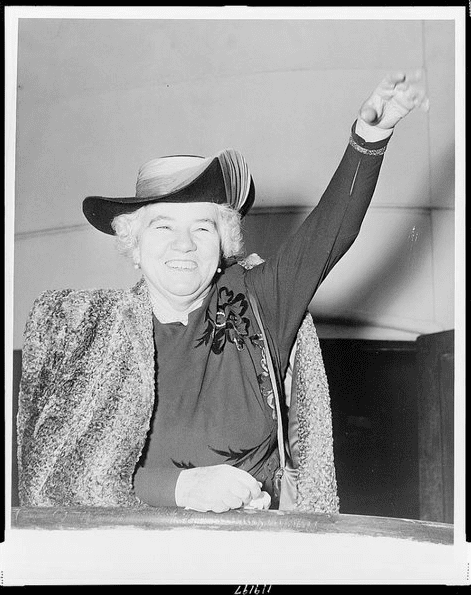

Elizabeth Kenny, half-length portrait, facing front, waving from the Queen Mary. World Telegram & Sun photo by Al Ravenna. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

Controversy over her technique did not die down and physicians made further attempts to discredit her concepts.8,9 A 1944 study by orthopedists reported that her method did not prevent paralysis and claimed that exercises performed prematurely were even harmful. Moreover, they accused her of misrepresenting her statistics by including polio cases that resolved spontaneously. She retorted, “Because I was only a nurse, they wouldn’t listen to me.”1

Kenny was notorious for her lack of tact and diplomacy. She did not exemplify the typical physician-nurse relationship at that time, which was almost like that of master and servant. Meanwhile, doctors resisted taking preemptory orders from a nurse with no formal medical training. Ironically, by presenting herself as an authority figure who was intolerant of dissenting views, she succumbed to the very traits that she had earlier identified as detrimental.

Regardless of opinion on her method, Kenny renewed interest in an area that badly needed attention.4 The field of rehabilitation medicine gained respect. Further, Kenny’s publicity increased the number of contributions to the March of Dimes, which funded vaccination research and assisted communities battered by epidemics.2 In 1951, she topped the Gallup Poll as the most admired woman, displacing even Eleanor Roosevelt. She grew to be an international icon whose stature rivaled that of Florence Nightingale and Marie Curie.

With the advent of vaccines, polio gradually ceased to be a menace and lost its influence in political discourse. So did the image of Kenny, which faded from public memory. Her story testifies to a case of deliberate forgetting, much of which was facilitated by critics who outlived her. Sister Kenny was nonetheless an effective change agent. Polio care was transformed in a relatively short time; immobilization was largely discontinued in the acute stage of the disease. In 1947, one physician saw a farmer in Georgia using discarded splints as stakes for garden beans!2

Sister Kenny was unwilling to be bogged down by the constraints of society. She exposed the gendered culture of the medical establishment to a wider audience. Her social disadvantages may have influenced the strategies and resources she used to convince others that her method was superior. Her life story is a testament to the relevance of open-mindedness and the importance of examining something new on its own merits rather than reliance on established ideas. By drawing attention to this issue with determination and perseverance, by striving to obtain scientific acceptance, by advertising her views and garnering public support, Sister Kenny succeeded in changing polio care.

References

- Kenny, Elizabeth, and Martha Ostenso. 1944. And They Shall Walk: The Life Story of Sister Elizabeth Kenny. New York, Dodd.

- Victor Cohn, Sister Kenny. The woman who challenged the doctors, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1976, 8vo, pp. [x], 302, illus., $16.50. Med Hist. 1978;22(1):97–8.

- Miller, Lois Maddox. 1941. “Sister Kenny vs Infantile Paralysis.” The Reader’s Digest 45: 1–6.

- Cole, Wallace Hasbrouk, John Florian Pohl, Miland Elbert Knapp, and Others. 1942. “The Kenny Method of Treatment for Infantile Paralysis.” Archives of Physical Therapy 23 (7): 399–418.

- Rogers N. Polio wars: Sister Kenny and the golden age of American medicine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2013.

- Potter RD. Sister Kennys Treatment for Infantile Paralysis. ” American Weekly August. 1941;17:4–13.

- Hulett JE join(‘ ’. The Kenny healing cult: Preliminary analysis of leadership and patterns of interaction. Am Sociol Rev. 1945;10(3):364.

- Daly MMI, Greenbaum J, Reilly ET, Weiss AM, Stimson PM. THE EARLY TREATMENT OF POLIOMYELITIS: WITH AN EVALUATION OF THE SISTER KENNY TREATMENT. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1942;118(17):1433–43.

- Gill AB. THE KENNY CONCEPTS AND TREATMENT OF INFANTILE PARALYSIS. JBJS. 1944;26(2):1.

ANAND RAJA DEVARAJ SUSHAMA, MD, works as Senior Resident in Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation in Government Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram. He lives in Kerala, India. He is currently pursuing a Masters in Anthropology. He is interested in rehabilitation medicine, disability studies, evolutionary medicine, and medical ethics.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 2 – Spring 2022

Leave a Reply