Hugh Tunstall-Pedoe

Dundee, Scotland, United Kingdom

Initiation

My initiation as a novice doctor at Guy’s Hospital, London (Fig 1) was as junior partner to the legendary King of Surgery and Queen of Nursing. It was 1964. Clinical students in London medical schools with first degrees at Cambridge University went back there for their final exams, predominantly pass or fail. I returned to Guy’s a minor celebrity, with honors in surgery.

Within hours I was accosted by the senior house officer in cardiothoracic surgery, owed three weeks of leave, asking me to act up by doing his locum, which meant forgoing my own holiday. Looking back now on how the hierarchy treated me, I met considerable formality (no gossip, teasing, or joking), but good manners, respect, generosity of spirit, and concealed, but suspected, affection.

The Guy’s Hospital cardiothoracic unit was led by Sir Russell, later Lord, Brock, President of the Royal College of Surgeons of London.1-3 Job, the male cardiothoracic ward, was Guy’s Hospital’s “holy of holies,” domain of the doyenne of Guy’s ward sisters, Angela Falwasser.4,5

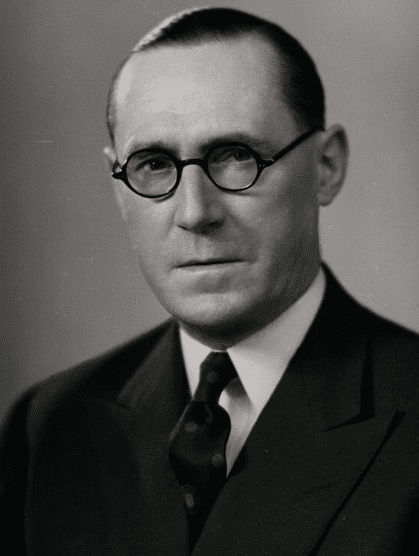

Russell Brock, king of surgery, a living legend

Russell Brock studied the anatomy of the bronchial tree and lung abscess, documenting 477 cases straddling the introduction of antibiotics.6 He moved to the mitral valve and pioneered surgery of mitral stenosis, pulmonary stenosis and Fallot’s tetralogy, among others. As a student, I observed the deference of his colleagues, but knew he did not suffer fools gladly. He became progressively more abrasive. Explanations came late. The card index record of patients on Job ward, contained one for Brock: admitted with atrial fibrillation. His colleagues realized that Brock’s supercharged, hyperactive behavior was thyrotoxic. After thyroidectomy, he calmed down, but still appeared disconcertingly brusque.

My first informal ward round with Brock was uncomplicated, except I used the phrase “operative intervention” which he found pretentious (as did I, as I said it).

While assisting with surgery on a patent ductus arteriosus, the retractor I was gripping moved. “Of course, this has slipped,” said Brock sounding irritated. “I am sorry, I cannot see.” I replied. Brock stopped operating, removed all the impedimenta, and gave me a conducted tour of the depths of the incision, pointing out where everything was, before resuming.

Later, I wrote to my parents about an encounter in my medical house-job days. Brock came for a consultation with a gaggle of students. After intensively interrogating me, he took me aside by the arm and said he hoped his difficult questioning of me had not upset me, adding “I was only trying to teach these students!”

This was the “brusque” President of the Royal College of Surgeons—imminently Lord Brock—to myself, a junior house officer. It was the first overt warmth I had from him, although I previously suspected it. Perhaps, knowing I would be using him for references, he decided to test me out, and then thought he had overdone it.

Obituaries from those who knew him well (particularly at the Royal College of Surgeons of London which he served for many years), confirmed what I divined earlier. An intensely hard-working, difficult-to-know, shy, private, person, he kept his own counsel, brusqueness and abrasiveness perhaps in compensation. A stickler for accurate language, he suffered fools badly. Yet he was a loyal supporter of juniors who earned his respect. Thyrotoxicosis was not mentioned.

“Russell Claude Brock: born 1903, qualified 1927, Surgeon to Guy’s and The Brompton Hospitals 1937-68, Assistant 1935-, then Editor of the Guy’s Hospital Reports 1939-60, Council of the Royal College of Surgeons 1949-66, President 1963-66, Knighted 1954, Life Peerage 1965 (Baron Brock of Wimbledon), retired (from NHS) 1968, died 1980.”1-3 (Figure 3)

Angela Falwasser, queen of nursing, “better to give than to receive”

Angela Falwasser was reputedly a German countess, but had an Edwardian childhood. She was the daughter of a clergyman, and the youngest of numerous siblings in Yorkshire. She decided on nursing at age three and was educated in her early years by her mother, a teacher, and started nursing training in 1925.4,5 Many of her era of ward sisters were unmarried—she would have trained when ward sisters were expected to resign on marriage. Before surgery moved to New Guy’s House in 1961, she had a bedroom and sitting room adjoining Job ward in the old surgical block, was on call at night, and came on duty promptly at 7:20 am, greeting and assessing each patient in turn. She conducted prayers on the ward at 8:30pm before retiring to her sitting room. Nursing training in the 1960s in Britain was predominantly by apprenticeship, later changing to university degrees. Completion of training earned the hospital badge, worn on the uniform (Figure 2). Angela Falwasser was of higher prestige than nursing officers in the matron’s office. She took new probationer nurses on her ward to perform basic procedures such as bed baths, to ensure they got them 100% right. Some young nurses feared the discipline on Job ward, while others loved it.

Medical and surgical teams in the 1960s were like traditional families. There was a dominant male (the consultant), a dominant female (the ward sister), and juniors fitted below. Nurses (largely female) were considered subservient to doctors (largely male), but Sister Falwasser’s Job ward was unquestionably hers, and the doctors were respected but visitors. It had a cathedral calm. Many patients were very ill and died there. Post-operative patients came straight back, going elsewhere only if they needed ventilating. By repute she had the skill of predicting which patients would survive major surgery and which not. Intravenous drips were for doctors, but on Job ward could mysteriously change arms.

I did a daily morning round with Sister Falwasser and a review later on. She vacated the nursing station, coming to meet me as I entered the ward, with a little smile—a petite woman, her hands tucked into her opposing sleeve cuffs. She saw me off later with a little bow, holding the ward door open for me to exit. I followed in the footsteps of many trainee surgeons, some subsequently very eminent. I remember my first ward round with her, rebuked only for referring to Penicillin V by its chemical name as phenoxymethylpenicillin.

I met Sister Falwasser twice after 1964. As house surgeon on take at Guy’s, I had a concussed, known methylated spirits drinker in Casualty. He was dirty and bloody—the protocol demanded admission for observation. The only available bed in New Guy’s House was a side-room in Job ward. Relieved it was the staff nurse who answered the telephone, I went up there later with some trepidation. As of old, Sister Falwasser met me with the little smile, hands tucked into opposite cuffs, and said, “There you are, doctor, you have come to see your patient.” She stood next to the old rogue’s bed, both smiling at me for approval, as if posing for a photograph. He was in clean bedding, in clean pajamas, immaculately clean. He knew which side his bread was buttered on—she had him eating out of her hand. No doubt she had used him to teach her student nurses.

Later, I heard that it was her last day at Guy’s on retiring. I went up to Job ward and joined a small queue of well-wishers at her desk. I told her that I could not hear that she was leaving without coming to say goodbye, but also to thank her on behalf of all the young doctors she had helped and looked after at the beginnings of their careers. To my dismay she began to weep. Pulling herself together she said tearfully, “Yes, it has really all rather been fun!”—her judgement on a lifetime of nursing service. Maybe young doctors featured in other ways in her earlier life, or someone lost in World War II.

This extraordinary woman shines through her obituaries.8 She was a practitioner of the Guy’s founding motto of 1721: “Dare Quam Accipere,” better to give than to receive (Figure 2). Thomas Guy would be proud of her! She was a shy, modest, but superb team leader, teaching by example; no chore in the perfect running of her ward was too menial for her, but it also ran like clockwork in her absence. Promoted sister in 1931 within an unusual three years of qualifying as a nurse, her years of bedside observation made her an outstanding clinician and diagnostician. Her devotion, empathy, and championing of her patients was matched by that for her staff—she ordered away any nurse or junior doctor in whom she detected incipient illness, and subsequently sent them up warm lemon drinks and sandwiches that she had made herself. She was a valued contributor in planning nursing services and the design of Guy’s ward blocks. On retirement, her former staff nurses, an elite group, were an extended family to her. She nursed her sick neighbors, helped with bed baths in the local hospital, and joined a group of volunteers that kept Winchester Cathedral’s interior well dusted! Her lifetime of giving (Dare) in nursing, followed her resolution to do so announced at age three.

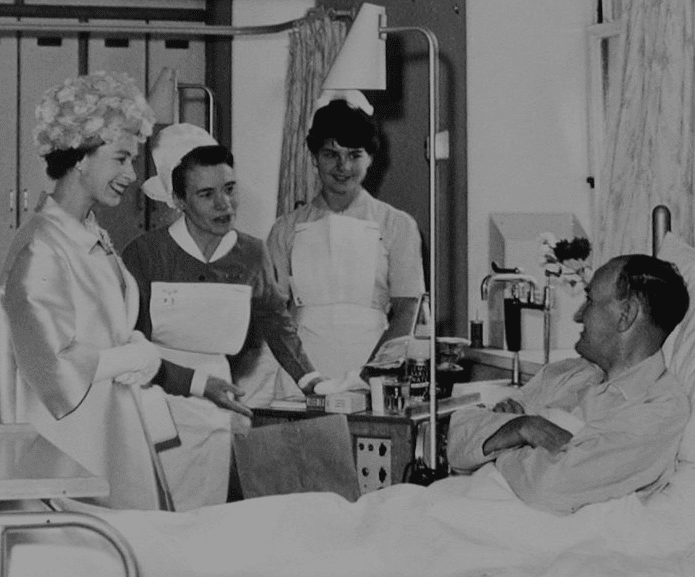

Opening of New Guy’s House (surgical block) 1962, Job ward. From left to right: Queen of England (Elizabeth II), Guy’s Queen of Nursing (Angela Falwasser), Guy’s nurse (Penny Dawes), unnamed surgical inpatient. Photo courtesy of Gordon Museum GKT Medical School KCL, with permission.

When the Guy’s Hospital Nurses’ League had its final meeting in 2010 (superseded by hospital mergers and a university takeover of teaching) her name, still legendary forty-five years after her retirement and eleven years after her death aged ninety-two, was greeted with a loud ovation. The myth that she was a countess survived for decades. Despite her shyness and modesty, she was in reality a queen!

“Angela Falwasser: born 1907, started nursing training 1925, Guy’s nursing home sister September 1931, ward-sister Job ward 1932-65, honored by MBE 1959, retired 1965, died 1999.”3,4,8 (Figure 4. Two queens together.)

Tailpiece

The renowned Guy’s Gordon (pathology) Museum contains, to this day, a resected rib tumor and its description, presented by Brock, dating from my first week with him in 1964. The presumptive diagnosis was primary osteogenic sarcoma. I had suggested it was secondary prostatic carcinoma, was overruled, but eventually proved right. One of the penalties of greatness is in attracting sycophantic falsehoods. In Brock, greatness went with generosity of spirit. A limited sample, but when I used him for job references, they always worked, so I guess he did not hold my ever proving him wrong to my disadvantage. Months later a capricious physician wrote a vindictive, confidential sign-up on my work, necessitating my rescue by others—no generosity of spirit there, and certainly not a great man—but that is another story!

References

- En.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russell_Brock_Baron_Brock.

- Munk’s Roll of the Royal College of Physicians of London http://history.rcplondon.ac.uk/inspiring physicians/lord-russell-claude-brock-baron-brock.

- “Brock, Russell Claude, Lord Brock of Wimbledon-Biographical entry- Plarr’s Lives of the Fellows Online” http://livesonline.rcseng.ac.uk/biogs/E000235b.htm.

- Royal College of Nursing Oral History Collection Ref T44. Interview with Angela Falwasser. Winchester 11th February 1992. Archives.rcn.org.uk/CalmView.Catalog&id=T%2F44.

- AN APPRECIATION: Sister Falwasser. Guy’ Hospital Gazette 1965, April 3; No 2001:161.

- RC Brock. Lung abscess. Blackwell Scientific Publications. Oxford 1952. (in the author’s possession).

- Andie Howard. The story of Guy’s Hospital Nurses’ League 1900-2010. GHNL 2010. ISBN 978-0-9567318-0-7.

- Obituaries of Angela Falwasser MBE. Guy’s Hospital Nurses’ League Journal (Centennial Edition) 2000; XXXV:59-62.

HUGH TUNSTALL-PEDOE, MA, MD, FRCP (London and Edinburgh), FFPH, FESC, semi-retired, is emeritus professor of cardiovascular epidemiology in Dundee University, Scotland, UK. He studied at Cambridge University and Guy’s Hospital and followed a career in medicine and cardiology in London before becoming a researcher in cardiovascular epidemiology. He moved to Scotland in 1981 to head a research group on cardiovascular disease, was Rapporteur of the WHO MONICA Project from 1979-2003, and initiated the Scottish Heart Health Extended Cohort (SHHEC) whose follow-up he continues. Three previous contributions to Hektoen International.

Acknowledgements: I wish to thank Andie Howard, historian of Guy’s Hospital Nurses’ League; Michael O’ Brien, Guy’s graduate 1962, former Guy’s consultant neurologist; and Bill Edwards, Curator of the Gordon Museum since 1999, for assistance with Guy’s memories and memorabilia. Any errors of fact, wrong, or distorted memories are my sole responsibility, as are the opinions expressed.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 2 – Spring 2022

2 responses

What a superb dissertation that brought back so many happy memories of a great training hospital in it’s heyday.

Graduating in 1965 I had the undoubted privilege of being exposed to Sir Russell Brock, his very fine and the best

surgical operator Donald Ross. I too met the renowned sister Falwasser on Job. Referring a patient on one of the

old ‘To and Fro’ forms on behalf of my boss Dr George Scott to Sir Russell then presenting the patient on his ward

round was a daunting exercise. ” The chest radiograph Doctor” No such thing as a chest X-ray for the great man.

Everybody had missed a small osteolytic fib deposit from a bronchogenic carcinoma… the rest is history.

Thank you Guy’s for what you gave me!

what a wonderful record of past. so accurately pictures both special characters. I was so grateful and respectful to both particularly sister F .I encountered both as sir Russells house surgeon. for a double stint which I had requested. ro be repeated. I suppose he felt ‘better the devil you know” and allowed this in 1956 . it influenced my whole career and thinking. how lucky I was. . such good description of reality of those days. I remember one night getting up sister F from her room on ward as I was faced with a poor man getting bigger and bigger I had no idea what to do .

sister appeared dressed in uniform without cuffs or hat reset the tube stopped the surgical emphysema and returned to bed with appropriate instructions.

what is not mentioned is how she saved the dean of guys life ,sir Rowan Boland who was admitted under mr grant Massie senior surgeon having fallen off his tractor and had part of his leg ground away. he was in her care for months as she nursed him back to walking health