Geoff Hoppe

Virginia, United States

A murder mystery might seem like a strange place to find hope, but hope is what Edgar Allan Poe’s mysteries can provide—if you know how to look. While Poe’s stories depict the macabre, they also demonstrate how a neurodiverse mind can find inclusion in a neurotypical society. Two instances in a seminal Poe story, “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” demonstrate characters thinking in a neurodiverse fashion. Poe’s imaginary literature provides a very real model of neurodiverse inclusion.

Neurodiversity is sociologist Judy Singer’s term for cognitive diagnoses like autism, dyslexia, and nonverbal learning disability. Singer’s term reframes these diagnoses as differences in perception and processing, rather than as weaknesses.1 Singer argues that neurodiversity offers valuable, unique perspectives.

Neurodiversity often comes with a price, however: isolation. Though neurodiverse conditions are sources of tremendous potential, living with a neurodiverse diagnosis poses problems. When you perceive and process information differently than most people, everyday things like employment and friendship can seem inaccessible. But when neurodiverse people are empowered to use their unique thinking, they can play irreplaceable roles. Poe’s stories show how neurodiversity can be a strength. As someone with nonverbal learning disorder (NLD), I see in Poe’s stories a reflection of my own thought process and how it might be useful.

NLD is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by poor organization, executive function deficit, and sensory processing difficulties. NLD is “the opposite of dyslexia,” as educator and NLD expert Scott Belsyzko describes it. “All the stuff that involves understanding information—relationships, concepts, ideas, patterns”2 are struggles for those with NLD. Because of this, many struggle to get a holistic, “big picture” view of a situation. To use the old cliche, people with NLD “can’t see the forest for the trees.”

If people with NLD struggle to see the forest, however, their view of each tree is often better than most neurotypicals. They perceive the world in more detail than neurotypicals, but struggle to process and integrate those details into a coherent whole. However, an NLD person will see those details with a clarity and thoroughness that normal people lack. If you misunderstand an issue, you may be missing a detail that someone with NLD would catch.

The value of this hyperfocus is captured in one of Poe’s most famous stories, “The Murders in the Rue Morgue.” In that story, the hero’s meticulous focus on detail is the key to cracking the case. “Rue Morgue” shows how the NLD neurotype might help solve society’s unsolvable problems.

With “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” Poe not only invented the modern detective story, he sketched a blueprint of disabled inclusion in an ableist world. The story follows a nameless narrator and his friend, Auguste Dupin. The pair try to clear a wrongly convicted man and solve a seemingly unsolvable murder. In two instances in the story, Dupin perceives and processes information like someone with NLD. Thinking this way gives him borderline preternatural abilities.

A startling example of this comes early in the story when Dupin effectively reads his friend’s mind. After fifteen minutes of walking together in silence, Dupin correctly guesses that his friend is thinking about a failed actor named Chantilly:

“Neither of us had spoken a syllable for fifteen minutes at least. All at once Dupin broke forth with these words: ‘He [Chantilly] is a very little fellow, that’s true, and would do better for the Theatre des Varieties.’ ‘There can be no doubt of that,’ I replied unwittingly . . . in an instant afterward I recollected myself, and my astonishment was profound . . . ‘How was it possible you should know I was thinking of [Chantilly]?’”

Dupin correctly guesses his friend’s fifteen-minute-long train of thought, predictably astonishing him in the process. As for how Dupin knew his friend was thinking of Chantilly, the answer to that lies in the way Dupin perceives and processes information.

In a virtuoso set piece, Dupin describes how perceiving seemingly unimportant details were keys to unlocking his friend’s train of thought. Dupin explains that his friend’s random behaviors—tripping on a cobblestone, mouthing the word “stereotomy,” glancing at the night sky—were all, to Dupin’s mind, clues to what was going on in his friend’s head. In one example, Dupin describes how reading his friend’s lips revealed his train of thought:

“. . . perceiving your lips move, I could not doubt that you murmured the word ‘stereotomy’ . . . I knew that you could not say to yourself ‘stereotomy’ without being brought to think of atomies, and thus the theories of Epicurus; and since, when we discussed this subject not very long ago, I mentioned to you how . . . the vague guesses of that noble Greek had met with confirmation in the late nebular cosmogony, I felt that you could not avoid casting your eyes upward to the nebula in Orion.”

Dupin can see the hidden, broader picture of his friend’s train of thought because of his hyperfocus on seemingly inconsequential details. Dupin’s thought process here would be familiar to most people with nonverbal learning disability whose minds fixate on small particulars (the “can’t see the forest for the trees” factor). The genius of “Rue Morgue” is that Poe reveals the practical use of this hyperfocus. Dupin divines the bigger picture of his friend’s train of thought, because of his hyperfocus on the details. Because Dupin sees his friend mouth the word “stereotomy”—a detail a neurotypical mind might overlook—he realizes that his friend will next think of “atomies” and Epicurus. Poe had the vision to see how a neurodiverse mode of perception could be a strength, and then build a scene around that perception. Dupin’s parlor trick mindreading is merely a setup, however, for the titular murders.

Dupin solves the murders in the Rue Morgue the same way he read his friend’s mind in the earlier scene. By focusing meticulously on several details the Parisian police have overlooked, Dupin constructs a radically different picture of the overall crime. In terms of the cliche, Dupin sees each tree in such detail that he realizes the forest is of a different type.

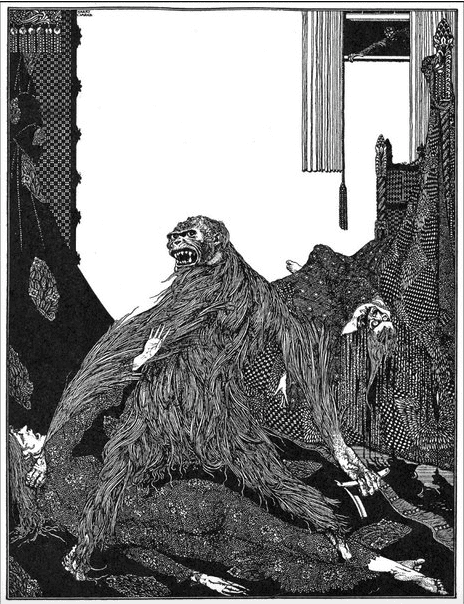

The titular murders in the Rue Morgue are perplexing. The crime scene, an apartment with locked doors and windows, has no apparent way in. The details are grisly and disordered: a corpse with a slashed throat, another shoved halfway up the chimney, a window locked, a large sum of money strewn about, and witness accounts of a strange, “foreign” voice coming from the apartment. The only possible motive belongs to a hapless bank teller. Earlier on the day of the murders, the teller delivered a large withdrawal to the victims. Predictably, the Parisian police arrest him.

Because the police try to fit the gory details to the motive’s overall picture, they arrest an innocent man. Since money is usually the motive behind such crimes, police assume it must be the motive here. Dupin’s detail-focused thinking leads him to a different conclusion.

The first detail that Dupin fixates on is the strange, “foreign” voice heard by witnesses. Dupin notes that each witness claimed to have heard a language they did not speak. Dupin realizes this detail invalidates the witnesses’ testimony: how can a witness be sure they heard, say, Russian, if they do not speak Russian? Two other details raise Dupin’s suspicion. First, the witnesses describe the voice as “quick and unequal.” Second, the witnesses say they could not hear any “sounds distinguishing words.” These three details—the “foreign” voice, its “quick and unequal” quality, and a lack of discernible words—lead Dupin to doubt one important part of the police’s overall picture: that the murderer was human at all.

Dupin similarly deconstructs the other component details of the police’s bigger picture. Dupin’s deconstruction is a longer version of the earlier scene where he read his friend’s mind, with details about the crime scene substituted for details about his friend’s behavior. For instance, by focusing meticulously on the window, Dupin deconstructs the notion that the room was closed from the inside. Dupin realizes that the nail holding the window shut is actually broken. Thus, a murderer could have used the window to enter and escape. One such realization leads to another, and Dupin ultimately realizes the crime was committed by an escaped orangutan.

While the murders in the Rue Morgue are fictitious, Dupin’s thinking is not. Managers and bosses with seemingly unsolvable problems could appeal to those with NLD for help in determining what details they are missing, and how those details might provide the key to the solutions they need. If there are problems with an organization’s processes, there may be problems with details that neurotypical minds overlook. The solutions to our society’s unsolvable problems may lie in approaching those problems with Dupin’s neurodiverse lens. Fortunately, people who think like that are available in the neurodiverse community, if society has the ethical courage to include them.

End notes

- “What is Neurodiversity,” accessed 9/8/2021, www.neurodiversityhub.org/what-is-neurodiversity.

- Caroline Miller, “What is Non-verbal Learning Disorder?”, Child Mind, What is Non-Verbal Learning Disorder | NVLD Symptoms | Child Mind Institute.

GEOFF HOPPE is a writer and freelance scholar who lives in Virginia. He was diagnosed with nonverbal learning disability (NLD) in adulthood, and organizes an online discussion group for people with NLD. He’s interested in the intersection of the humanities and disability, and in neurodiversity more broadly.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 2 – Spring 2022

Leave a Reply