Utkarsh G. Hingmire

Nagpur, India

|

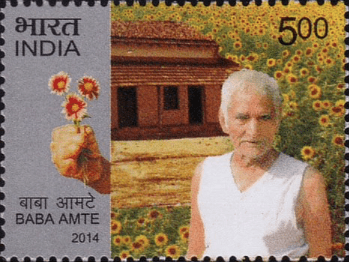

| Baba Amte. This file is a copyrighted work of the Government of India, licensed under the Government Open Data License – India (GODL). Via Wikimedia. |

Murlidhar Devidas Amte, affectionately known as Baba Amte, was a lawyer who left his lucrative legal career to devote his life to the treatment of patients suffering from leprosy.1 If one was to describe his life in a few sentences it would be “I sought my soul, my soul I could not see; I sought my god, my god eluded me; I sought my brother and I found all three.”

Baba Amte was born on December 26, 1914, in India at Hinganghat in Maharashtra. Since his childhood he showed both humane and rebellious traits, and his resolve solidified even more when his father bopped him for dining with the servants.2 He remained concerned for the plight of the disadvantaged in his adulthood and even when he qualified as a lawyer in 1938.3 Once while visiting his family estate, he saw the pitiful condition of his tenants in poverty and was dismayed by the scene. He felt bad because the laborers who toiled in the field for twelve hours earned less than what he would earn by some chattering.3 He used his legal insight to help the deprived by defending the rights of sweepers and weavers. Soon he was nominated as the Vice-Chairman of the Warora Municipality and president of the scavengers union.2

Baba’s life changed when the sweepers of the Warora Municipal Corporation approached him to defend their case. Baba chose to represent them but wanted to have first-hand experience of their issue. The problem was that they were being overworked. One day while cleaning the latrines, he came across a bundle of moving cloths. To his astonishment he found that it was a human being in the last stage of leprosy, “. . . a rotting mass of human flesh with two holes in the place of a nose, without a trace of fingers or toes, and with worms in the sores that had once been nostrils and eye-sockets.”3 Witnessing this scene he panicked and ran away, afraid of catching the infection. After some contemplation, he realized that his actions were wrong, and he returned to the man and made a temporary shelter of bamboo thatch to protect him. This experience led him to devote his life to the ones who were eschewed by society.2

He now embarked on a new journey. He tried to read everything that was available in the literature about leprosy, how society treated those afflicted by the disease, and about the people who had sacrificed their lives in the service of leprosy victims.3 He visited leprosariums to study the methods of rehabilitation and treatment. Even that was not sufficient, so he sought admission to the Calcutta School of Tropical Medicine. At first the doctor in charge of the institution refused to admit him, but after constant persistence he was allowed to take a special course in the treatment of leprosy. Around this time leprosy treatment was revolutionized by a new sulphone drug known as DDS.3 The problem was that most patients needed long-term treatment of around two to three years and they could not afford this much. The only option left was to beg, which destroyed their self-respect. To overcome this problem Baba decided to set up a colony where they could employ themselves and reside permanently or until the treatment was concluded.2

So in 1950 he established Anandwan (forest of joy), the first colony to treat leprosy on the outskirts of Warora. The state government allocated fifty acres of barren land which was converted into a farm. A clinic was also set up, and the government again allocated fifty acres of land. By the 1960s, six hundred patients were staying in Anandwan, and around four hundred of them received treatment weekly. A similar colony called Ashokwan was set up near Nagpur which had almost one-hundred self-reliant inhabitants.

Baba worked on many projects thereafter. He also inspired his sons, and they became doctors and dedicated their life to serve humanity.2

References

- Rode, S. BABA AMTE’S SOCIAL CULTURAL VISION-A FRESH LIGHT ON SOCIAL REFORM MOVEMENT IN CONTEMPORARY MAHARASHTRA (Summary). in Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 1983. JSTOR.

- Shri Murlidhar Devdas Amte Recipient of Jamnalal Bajaj Award for Constructive Work-1979. 2017; Available from: https://www.jamnalalbajajfoundation.org/Media/pdf/JBA_1979_Bio_Murlidhar_Amte.pdf.

- Swamy, R.J.V., The makings of a social entrepreneur: The case of Baba Amte. 1990. 15(4): p. 29-38.

UTKARSH G. HINGMIRE, B.A.L.L.B (Hons.), is a fourth year law student at National Law University, Nagpur, India, where he was appreciated by Justice B.N. Srikrishnan (Supreme Court of India) for presenting a paper on Indian Jurisprudence. Hingmire has contributed to the existing literature on changing dynamics of Intellectual Property in India. He was adjudged as Quarter finalist in the 1st RGNUL Sports and Entertainment law National Mediation Competition, as was acknowledged by Peace Keeping and Conflict Resolution Team (PACT). He is a fellow at Dexterity Global a National organization powering the next generation of leaders through educational opportunities and training. Hingmire being from a minority has represented his community at district level.

Leave a Reply