Nicholas Kang

Auckland, New Zealand

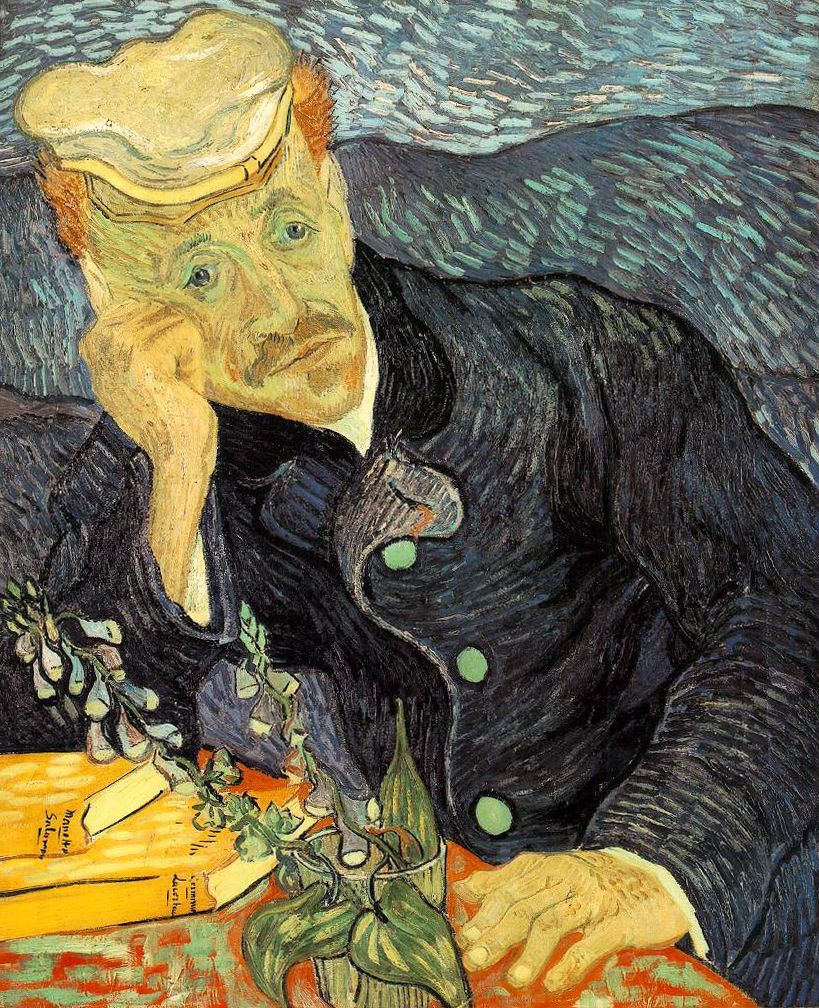

On a spring evening in New York, a portrait is unveiled before a crowded auction room. It pictures an older man wearing a dark blue coat with luminous green buttons. His elbow rests on a red table beside two yellow books. In front of him is a glass with faded purple flowers whose stems lean like the man himself. In the background, a shimmering turquoise sky illuminates hills of cobalt blue and seems to flow strangely over the man’s jacket. His sallow face and weary posture bear the “heartbroken expression of our time” in the words of the painter.1

The van Gogh fetches a staggering price, eclipsing all records to become the most expensive work of art ever sold. Its subject is the mysterious physician who befriended the troubled artist in his final months, tended his wounds, and watched over his deathbed. A hundred years after their fateful meeting, the sale of van Gogh’s masterpiece makes history. But history is still deciding whether the portrait’s melancholy figure was ardent hero or artful villain.

Auvers-sur-Oise, 1890

After a year of confinement in a mental asylum, Vincent van Gogh arrived at the picturesque village of Auvers seeking respite from his suffering. There he was introduced to Paul-Ferdinand Gachet: physician, amateur painter, and art collector.

The sixty-one-year-old doctor was already a familiar figure in the nineteenth-century art world. Cézanne and Guillaumin had enjoyed his patronage, while Renoir, Manet, and Pissarro were among his former patients. Paintings from his collection had featured at the very first Impressionist exhibition organized by Monet and Degas, and his portrait had been exhibited years earlier at the Paris Salon. Gachet readily accepted artwork in exchange for his services, and he had also painted several passable works of his own that imitated the artists he admired.2

The doctor who knew “all the Impressionists”3 seemed well suited to oversee van Gogh’s recovery. He had an interest in diseases of the mind and had run a practice in Paris advertising “special treatment of nervous ailments.”4 He formed the view that van Gogh’s strange condition had “nothing to do with madness” and was almost certainly curable.5 This was either vain hope or fatal misjudgment, given that Gachet’s remedies were mostly herbal concoctions and homeopathic preparations. Van Gogh’s impressions of the aging physician left him feeling decidedly less optimistic: “I think we must not count on Dr. Gachet at all. First of all, he is sicker than I am.”6

Before long, van Gogh began a portrait of the doctor. Their vague physical resemblance unnerved the painter, who began to project his own fragile mental state onto his sitter.7 In what was effectively a self-portrait mirroring his own existence rather than a true likeness of his model, van Gogh transfigured doctor into patient—the forlorn gaze a distorted perception of a shared affliction.8 “I painted a portrait of Dr. Gachet with an expression of melancholy,” he wrote. “Sad and yet gentle, but clear and intelligent—this is how one ought to paint many portraits.”9

Gachet advised van Gogh not to dwell on his recent problems and encouraged him to work. Van Gogh did exactly that. In his seventy days in Auvers, he finished a painting a day. The doctor quickly recognized van Gogh’s prodigious talent and “did not see any reason for a return of the malady,” believing him to be “entirely recovered.”10 Van Gogh took comfort in Gachet’s attentions and came to regard him as a “true friend.”11 But inevitably, the artist’s volatile temperament began to test Gachet’s forbearance, echoing the familiar pattern of faltering relationships to which van Gogh was prone.

When the tragedy struck, Gachet was summoned, tended to the gunshot wound, sent urgent word to van Gogh’s relatives, and kept vigil over the deathbed. The next day he spoke at van Gogh’s funeral but barely managed a few words before being overwhelmed with grief. In the aftermath of the suicide, Gachet’s letters to van Gogh’s family brought great consolation, describing the painter as “exceptional” and remembering him as “a giant.”12 Van Gogh’s sister-in-law Johanna wrote, “Doctor Gachet . . . continued to honor Vincent’s memory with rare piety, which became a form of worship, touching in its simplicity and sincerity.”13

Conspiracy theories

Over the course of the twentieth century, the Portrait of Doctor Gachet came to be regarded as a unique and revolutionary painting. The pensive gaze of its subject spoke to a whole new generation of Expressionist painters and was universally admired for its haunting, timeless quality.14

Paradoxically, Gachet’s own legacy came to be challenged. Some accused him of profiteering from his unique coterie of patients, calling him “a foresighted collector . . . vigilantly guarding his sudden fortune.”15 Others questioned the way in which he had appropriated the canvases left behind after van Gogh’s funeral.16

History began to blame Gachet for failing to prevent van Gogh’s death. His medical oversight was condemned as negligent at best and recklessly indifferent at worst. He was branded a charlatan for his use of home-grown potions and elixirs, and was suspected of overdosing van Gogh with digitalis from the foxglove plant in his portrait.17

One critic claimed that Gachet secretly detested van Gogh and was consumed with envy. In their view, the doctor was not van Gogh’s “last friend on earth” as popularly believed, but a “grotesque Cerberus in a blue jacket” who was the “direct, effective, and sufficient cause of his death”:

“And yet more than ever I believe it was because of Doctor Gachet of Auvers- sur-Oise, because of him I say, that van Gogh on that day, the day he committed suicide in Auvers-sur-Oise, departed this life.”18

Twenty-first century scholars now suggest that van Gogh may not have committed suicide after all, but was actually the victim of an accidental shooting.19 This hypothesis has spawned a raft of new theories—some more plausible than others—to explain the fatal gunshot wound.

In one such version of events, Gachet is alleged to have murdered van Gogh in order to end the painter’s lecherous advances toward the doctor’s daughter.20

Forgery scandal

Doubts about Gachet ought to have been assuaged when paintings from his estate were donated to the Musée du Louvre after World War II. The impact of this posthumous act of largesse, however, was the precise opposite. Gachet soon faced sensational new allegations regarding the authenticity of works in his prized collection.21,22

Foremost among the alleged counterfeits was a second version of Gachet’s portrait. The doctor had maintained that van Gogh painted the copy for him as a “token of fellowship and gratitude,”23 yet no mention of a second portrait could be found in the artist’s letters. Moreover, the second version appeared simplified—lacking the books, glass, and coat buttons of the original, as well as its more elaborate background. Above all, the doctor’s countenance in the second picture was considered “a very weak replica . . . missing the piercing look of [the original].”24

The supposition that Gachet tried to pass off his work as van Gogh’s swiftly added to his notoriety. When Portrait of Doctor Gachet sold at auction in 1990 for $82.5 million—a record unsurpassed for the next fourteen years—debate over the doctor’s collection reached its apogee. By now there was simply too much at stake for auction houses, museums, collectors, and insurers to ignore suspicion about the infamous doctor who “painted in his spare moments.”25

The Musée d’Orsay attempted to settle the matter once and for all. The most controversial works in Gachet’s collection were subjected to forensic analysis, with the findings announced in a touring exhibition across Europe and the United States. The verdict was prosaic if not predictable; the paintings were genuine but included some “weak pieces whose mediocrity offends our admiration for those masters.”26 Not everyone was persuaded.27

Final thoughts

Physician, painter, collector, and devotee, Paul-Ferdinand Gachet was among the first supporters of the avant-garde artistic movement of the late nineteenth century. He treated the mental and physical afflictions of its chief protagonists and became friend and muse to some of the greatest figures in Western art. Esteemed during life and maligned after death, debate continues over the controversial doctor immortalized in van Gogh’s celebrated portrait.

Notes

- Vincent van Gogh, “Letter to Paul Gauguin, Auvers-sur-Oise, circa June 17, 1890” in The Complete Letters of Vincent van Gogh, Greenwich, Connecticut: New York Graphic Society, 1958.

- Anne Distel and Susan Alyson Stein, Cezanne to Van Gogh: The Collection of Doctor Gachet, (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999).

- Theo van Gogh, “Letter to Vincent van Gogh, Paris, October 4, 1889” in Complete Letters.

- Paul Gachet fils, “Dr. P. F. Gachet, Curriculum Vitae compose d’apres souvenirs et documents par Paul Gachet, Auvers 1928,” in Cezanne to Van Gogh: The Collection of Doctor Gachet, ed. Anne Distel and Susan Alyson Stein, (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999), 273-78.

- Theo van Gogh, “Letter to Vincent van Gogh, Paris, March 29, 1890” in Complete Letters.

- Vincent van Gogh, “Letter to Theo van Gogh, Auvers-sur-Oise, May 23, 1890” in Complete Letters.

- Steven Naifeh, Gregory White Smith. Van Gogh: The Life. (New York. Penguin Random House, 2011), 839, note 277 in http://vangoghbiography.com/notes.php

- Cynthia Saltzman, Portrait of Dr. Gachet: the Story of a van Gogh Masterpiece (New York: Viking Penguin, 1998), 40.

- Vincent van Gogh, “Letter to Willemien van Gogh, Auvers-sur-Oise, June 12, 1890” in Complete Letters.

- Theo van Gogh, “Letter to Vincent van Gogh, Paris, June 5, 1890” in Complete Letters.

- Vincent van Gogh, “Letter to Willemien van Gogh, Auvers-sur-Oise, June 5 1890” in Complete Letters.

- Dr. Gachet, Letter to Theo van Gogh, circa August 15, 1890, Van Gogh Museum Archives, b3266 V/1966.

- Johanna van Gogh- Bonger, in Complete Letters, vol. 1, p. L1.

- Cynthia Saltzman, Portrait of Dr. Gachet: the Story of a van Gogh Masterpiece (New York: Viking Penguin, 1998).

- A. van Bever, “Les Ainés: Un peintre maudit, Vincent van Gogh,” in La Plume, June 15, 1905, 596.

- Adeline Carrié, “Recollections on Vincent van Gogh’s Stay in Auvers-sur-Oise,” in Van Gogh: A Retrospective, ed. Stein (New York: Hugh Lauter Levin Associates and Macmillan, 1986), 216-217.

- Thomas C. Lee, “Van Gogh’s Vision: Digitalis Intoxication?”, Journal of the American Medical Association 245, no. 7 (Feb 1981): 727.

- Antonin Artaud. “Van Gogh: Le suicidé de la société,” K éditeur, Paris 1947.

- Naifeh and Smith, Van Gogh, 869-879.

- Nick van der Leek, The Murder of Vincent van Gogh, (Irvine: Shakedown, 2018).

- “Ces toiles sont-elles de Van Gogh?” (“Are these paintings by van Gogh?”), Le Figaro littéraire, Dec 4, 1954.

- Louis Anfray, “La vérité torturée: Vincent van Gogh à Auvers-sur-Oise,” Art-Documents, no.43, April, 1954.

- Paul Gachet, Le Docteur Gachet et Murer: Deux amis des impressionnistes, (Paris: Éditions de Musées Nationaux, 1956), 135-38.

- Faille, J.B. de la. The Works of Vincent van Gogh: His Paintings and Drawings, (Amsterdam: Meulenhoff International, 1970).

- Theo van Gogh, “Letter to Vincent van Gogh, Paris, October 4, 1889” in Complete Letters.

- Anne Distel and Susan Alyson Stein, Cezanne to Van Gogh: The Collection of Doctor Gachet, (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999), 17.

- Martin Bailey, “Authenticity debate continues to tarnish Dr Gachet’s Cézanne and van Gogh donations at Grand Palais exhibition,” The Art Newspaper, March 1, 1999.

NICHOLAS KANG, FRACS, studied medicine at the University of Sydney. He has written two other essays published in Hektoen International.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Special Issue – Fall 2021

Leave a Reply