Enrique Chaves-Carballo

Overland Park, Kansas, United States

|

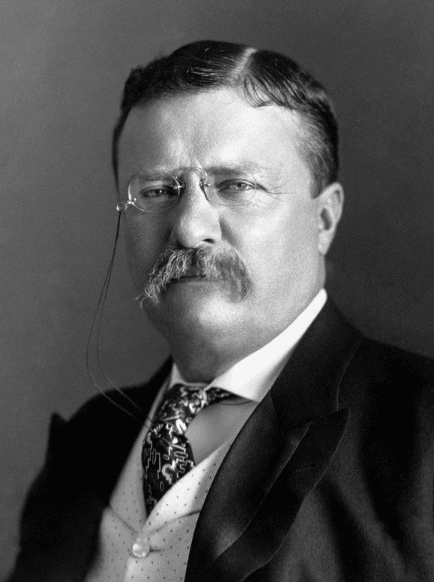

| Theodore Roosevelt. Portrait, c. 1904. Via Wikimedia. Public domain. |

Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. (1858–1919)

President Theodore Roosevelt envisioned an interoceanic canal as indispensable for American “dominance at the seas.”1 An isthmian canal would facilitate rapid deployment of U.S. Navy ships from Atlantic to Pacific Oceans, bypassing the arduous 2,000-mile trip around the tip of South America. However, construction of the Panama Canal—the most ambitious American engineering enterprise at the time—required a labor force capable of removing millions of cubic yards of dirt and rocks. Ability to survive the demands of an inhospitable climate and purported innate resistance to tropical diseases made workers from the neighboring West Indies (mainly from Jamaica and Barbados) an ideal target for recruitment by canal authorities.2 Requirements for employment included good health, ability to read and write, and willingness to work ten hours a day under incessant rain and oppressive heat. In return, applicants were enticed with free passage to Panama, repatriation after twenty months of service, free health care, and limited housing.2

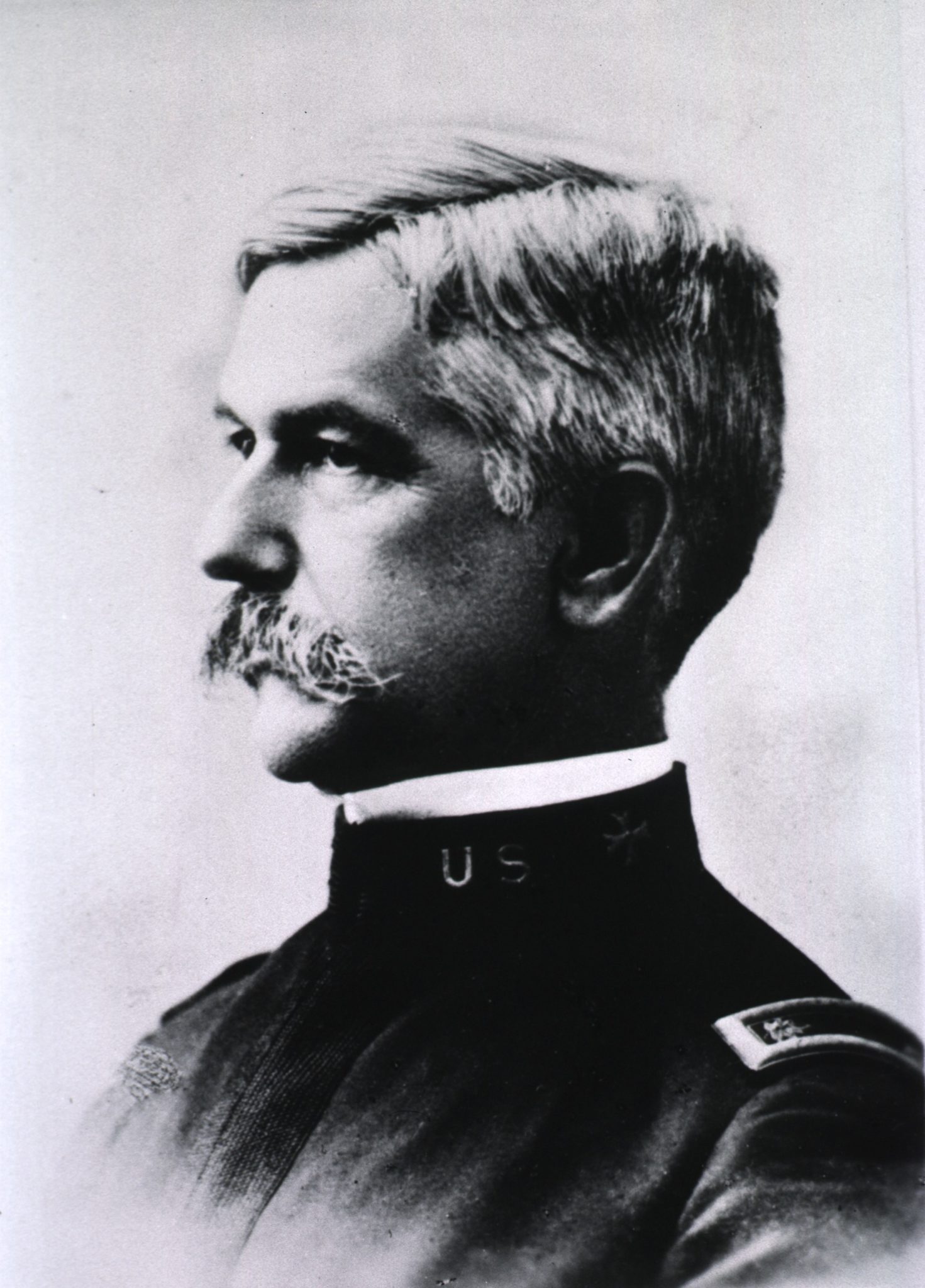

William C. Gorgas (1854–1920)

President Roosevelt also recognized the importance of sanitation as a requisite for the successful completion of the canal enterprise and appointed in 1904 Major William Gorgas as Chief Sanitary Officer of the Isthmian Canal Commission (the agency mandated by Congress to oversee all operations related to the construction of an interoceanic canal).3 Gorgas was highly qualified to lead the crusade against tropical diseases in Panama, since he had seen at least a thousand cases of yellow fever and successfully eradicated yellow fever in Havana after implementing rigorous mosquito-control measures at the turn of the century.4

At the peak of canal activity, more than 50,000 workers from the West Indies, Europe, and Asia were employed. Skilled white laborers were paid in U.S. dollars (“gold roll”), while non-white unskilled workers were paid in Colombian pesos (“silver roll”), which were equivalent to only half of the gold roll wages. Wages were ten cents an hour for ten hours a day, six days a week.2 Such discrimination pervaded life in the Canal Zone, a 500-square-mile strip of land conceded by Panama to the U.S. and governed strictly under U.S. rules and laws. Non-white workers were not allowed to benefit from individual housing and lived in crowded and poorly ventilated barracks. Amenities such as movies, pool parlors, swimming pools, and access to commissaries for cheaper clothing and food were not permitted for silver-roll personnel. Segregation was rampant and most facilities had separate entrances for white and non-white employees.2

Working for the canal enterprise entailed exposure to heavy machinery including locomotives, ninety-five-ton Bucyrus steam shovels, and transport of sixty-one million pounds of dynamite with frequent deadly premature detonations.5 On a single day, twenty-three men died and forty were injured when a blast of twenty-two tons of dynamite detonated unexpectedly.5 In addition, daily slides of tons of dirt and rock resulted in inevitable deaths. Death rates were in stark contrast: for the first semester of 1906, death rates were fifty-nine per thousand for non-whites compared to only seventeen per thousand for white employees.6

Medical cases

Authorities kept detailed statistics on deaths, hospital admissions, and diseases among canal workers. An analysis of 500 fatal medical cases included 450 non-white laborers, forty-six white European workers (Spanish, Italian, and Greek), two white Americans, one Asian, and one Hindu.7 A review of 4,806 autopsies performed between 1904 and 1918 among canal employees found respiratory ailments as leading causes of death (33%) with pneumonia in 844 cases and tuberculosis in 743 cases.8 These were followed by 341 cases of malaria (hemoglobinuric fever) (7%); 339 cases of external trauma or accidents (7%); 284 cases of chronic nephritis (5%); 210 cases of dysentery (4%); and 168 cases of typhoid (3%).8 A detailed analysis for possible tuberculosis risk factors revealed crowded living barracks, poverty, and lack of education to be contributing factors.9 However, no serious efforts were made by authorities to improve the existing poor living conditions among non-white workers.

Surgical cases

A review of all the surgical cases done at Ancon Hospital during the years 1910–1912 determined that of 22,000 cases treated, about half or 11,651 were of traumatic origin.10 The leading causes of trauma were listed as: mining accidents (4,639), fractures (1,205), cutting instruments (1,025), railroad mishaps (804), falls (591), sprains (546), and amputations (468). Working on the isthmian canal as an unskilled laborer was a most dangerous occupation.

|

| Major William C. Gorgas (1854–1920). Photoprint. National Library of Medicine. Public domain. |

Malaria

Among the many tropical diseases encountered on the isthmus, none caused more disability than malaria. In 1906, malaria affected 82.1% of the workforce!11 Although rarely fatal, malaria disabled victims for at least two weeks and caused excessive debility and absenteeism. From January 1905 to September 1910, 83,000 patients were admitted to Ancon Hospital.11 Of these, 41,000 (49%) had a diagnosis of malaria. A review of the total cases of malaria recorded during the fifteen-year period from 1904 to 1918 disclosed 104,296 cases, an average admission rate of 206.5, and a death rate of 24.19 per thousand employees.11 The number of deaths from malaria was nearly a thousand during this period, among more than half a million employees (948 deaths among 558,794 employees).11 Following the introduction of mosquito-control measures, the incidence of malaria decreased by nearly 90%.12 Antimalarial treatment consisted of ten grains (650 mg) of quinine sulfate taken orally three times daily. Forty thousand doses were prescribed daily among canal employees.13

Yellow fever

Yellow fever was the most feared tropical scourge because of its high mortality. Its presence caused mass exodus of employees. Detailed statistics kept at Ancon Hospital, where all yellow fever patients were admitted, showed 246 yellow fever admissions between July 1904 and December 1906 and a mortality of 34%.14 Treatment consisted of complete bed rest, nothing by mouth except sips of iced champagne, and meticulous monitoring of urinary output. The onset of black vomit heralded a fatal outcome. Yellow fever was eliminated from Panama using mosquito control measures implemented by Gorgas. The last case of yellow fever in Panama was recorded on December 7, 1906.14

Typhoid fever

Typhoid fever was responsible for 168 cases or 3.5% of deaths among canal workers.15 A study of 195 cases seen at Ancon Hospital between July 1909 and July 1913 found splenomegaly in 75% of cases, a useful clinical sign.15 There were only seventeen deaths, for a mortality of 8.7%. Conservative treatment consisted of a limited diet, tap-water sponge baths when fever was more than 102.5 degrees Fahrenheit, and phenyl salicylate in ten-grain (650 mg) doses three times a day during convalescence.

Intestinal parasites

Despite public health regulations applied by health authorities such as sewage disposal, potable water, and wearing of shoes, intestinal parasites were common among hospitalized patients. A study of 300 West Indian patients interned at Ancon Hospital in 1911 disclosed the following percentages of positive stools: hookworm, 37.9; trichuris (whipworm), 46.7; ascariasis (roundworm), 4.0; strongyloides, 20; and oxyuris (pinworms), 1.8.16 Comparison with results of a previous study done in 1906 showed a lower incidence of parasitic infestations, attesting to the efficacy of public health measures in reducing the burden of intestinal parasites among canal employees.16

Syphilis

Syphilis was common among canal workers. In a series of 8,226 non-white patients admitted to Ancon Hospital from December 1911 to October 1913, 6% were found to be syphilitic.17 The recently introduced Wasserman test was positive in 82.6% of clinically suspected cases.

Salvarsan (arsphenamine) had been used in the treatment of syphilis at Ancon Hospital since 1911. Adverse reactions usually followed two to four hours after the administration of Salvarsan. These were characterized by chills, fever, vomiting, headache, backache, and generalized pain. Despite these reactions, Salvarsan became the treatment of choice as it effectively reduced the number of hospitalization days from forty to fourteen in cases of secondary syphilis.17

Construction of the Panama Canal was both an engineering feat and a triumph of American preventive medicine. The failed French attempt to build an isthmian canal (1881–1889) cost 22,000 lives, while the American effort (1904-1914) resulted in 5,609 deaths—a reduction of almost 80%. At the peak of canal activities, 102 American physicians and 130 trained nurses provided excellent care to all the sick.18 Nevertheless, sick wards were segregated according to skin color.

Although health authorities recognized poor nutrition, crowded living conditions, and hazardous working environment as important risk factors for diseases and deaths among canal workers, administrators failed to remedy these adverse determinants and little was done to improve existing living and working conditions among non-white canal employees. The superior medical skills and facilities were insufficient to erase the indelible stains of contempt and racial discrimination that pervaded the American canal enterprise against an indispensable and dedicated West Indian labor force.19 West Indian workers sacrificed not only life and limb but also their dignity to make Roosevelt’s dream a reality. Many years later, their descendants recalled vividly the deep scars their ancestors carried for the rest of their lives.20,21,22

Notes

- Theodore Roosevelt, Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Navy (1888–1889), realized American naval forces were not fully prepared to engage in any conflict against Japan, Spain, or Germany. He concentrated his efforts to correct these deficiencies and convert the U.S. into a world-class maritime power.

- Previous attempt by the French to build a sea-level canal in Panama (1881–1889) failed because of poor administration, widespread corruption, and uncontrolled tropical diseases (mainly yellow fever and malaria).

- The total excavation of the Panama Canal amounted to 310,737,963 cubic yards (78,146,906 by the French and 232,353,000 by the Americans) at a total cost of $645 million ($270 million by the French and $375 million by the Americans) and 27,609 lives (22,000 by the French and 5,609 by the Americans).

- Workers from the West Indies (mainly Jamaica and Barbados) preferred to be designated as African-Caribbean or Afro-Antillean (Antilles refers to the Caribbean islands). They were brought from Africa by English and French colonists to work as slaves in Caribbean sugar and coffee plantations.

- The Isthmian Canal Commission (ICC) was created by U.S. Congress in 1889 to oversee all matters and expenditures related to the construction of the Panama Canal. Unfortunately, all members except one had never visited Panama and did not agree with Gorgas’ sanitation plan, considering his requests for materials and expenditures as outlandish and asked twice for his removal and replacement with “men of more practical ideas.”

- Gorgas was Chief Sanitary Officer in Havana from 1898 to 1902, a city of 300,000 inhabitants, where yellow fever had been endemic for 150 years. Gorgas was able to eradicate yellow fever in Havana by applying the findings of the Reed Yellow Fever Board incriminating the mosquito as vector and eliminating its breeding places.

- West Indian canal workers preferred cooking their own native meals based on high-carbohydrate, low-protein foods (maize or corn, yucca or cassava, yams, plantain, and sancocho—a stew of vegetables and what little meat was available). Government messes were available to non-white workers at twenty-seven cents per day deducted from their salaries. The bill of fare consisted of bread (a third of a loaf), jam, and cocoa for breakfast; bread, vermicelli and vegetable soup, stewed beef and Spanish sauce, and coffee for dinner; and for supper, bread, soup made of dry split peas and rice, yams or sweet potatoes, boiled beef with dumplings, tea, and an orange or apple. However, only one-sixth of the workers availed themselves of this nutritious fare and the rest lived as before, cooking their own meals and becoming “grievously underfed.”

- Pneumonia was probably caused by pneumococcus bacillus. West-Indian natives appeared to lack innate immunity to this microbe and succumbed readily to pneumococcal infections.

- Malaria is caused by several intraerythrocytic parasites (most commonly Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium falciparum, and Plasmodium malariae). P. vivax malaria is also known as tertian fever and P. falciparum as quartan, estivo-autumnal, or malignant fever. The latter had the highest mortality due to hemoglobinuria causing renal failure.

- Quinine, an antimalarial alkaloid derived from the Peruvian or cinchona bark, was at the time the most effective agent against P. falciparum malaria. Common side effects were nausea, tinnitus, dysphoria, and deafness (cinchonism). Canal workers were reluctant to take quinine because of its bitter taste but took it readily as tonic water containing five grains or 325 mg quinine each ounce.

- Malaria and yellow fever were caused by two different species of mosquitoes: Anopheles for the former and Aedes for the latter. Each species of mosquito had different habitats and breeding sites, requiring more laborious and expensive species-specific control measures.

- Mosquito-control measures introduced by Gorgas consisted of insect fumigation with sulfur or pyrethrum, spraying oil over ponds and swamps to kill mosquito larvae, drainage of breeding sites (standing water, cisterns, and water barrels), installing concrete or tile drain ditches, screening windows, and hand-catching mosquitoes (at one cent per mosquito). Gorgas estimated that drainage of about one hundred square miles of territory required construction of eight-and-a-half million feet of tile, concrete, and open-soil ditches.

- Joseph Bucklin Bishop, secretary of the Isthmian Canal Commission, began publishing the Canal Record in 1907, a weekly factual account of the activities surrounding the excavation of the canal. Bishop also published a comprehensive 459-page book The Panama Gateway (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1913) detailing the history and events leading to the successful completion of the isthmian canal.

References

- McCullough D. The Path Between the Seas. The Creation of the Panama Canal (1870-1914). New York: Simon and Shuster, 250-255.

- McCullough, Path Between the Seas, 471-474.

- Gorgas WC. Sanitation in Panama. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1916, 146-147.

- Gorgas, Sanitation, 72-73.

- McCullough, Path Between the Seas, 545-546.

- McCullough, Path Between the Seas, 501.

- Deeks WE, Baetz WG. An analysis of 500 fatal medical cases in the tropics. Proceedings, 1913; 6 (Part 1):14-43.

- Clark HC. A chart presenting the incidence of the more common causes of death on the Panama Canal Zone, as found at autopsy during the years 1904 to 1916, inclusive. Proceedings, 1917; 10 (Part 2):20-23.

- Clark HC. Tuberculosis of the negro race as seen in Panama Canal Zone. Proceedings, 1915;8 (Parts 1 and 2):19-43.

- Herrick AB. A brief outline of the surgical work done at Ancon Hospital during the years 1910, 1911 and 1912. Proceedings, 1913; 6 (Part 1):8-13.

- Hanson H. A review of the malaria incidence on the Canal Zone (Period of 1904 to 1918, inclusive.) Proceedings 1919;12 (Parts 1 and 2):27-29.

- Simmons JS. Malaria in Panama. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1939, 122-123.

- Gorgas, Sanitation, 221.

- Clendening History of Medicine Library Exhibit. The Panama Canal: A Triumph of American Medicine, www.kumc.edu/Panama-Canal (accessed September 9, 2021).

- Baetz WG, Bates LB. Typhoid fever in the Canal Zone. Proceedings, 1913; 6 (Part 1):68-83.

- Darling ST. The intestinal worms of three hundred insane patients detected by special methods. Proceedings, 1911; 4 (Part 1):41-48.

- Baetz WG. Syphilis in colored canal laborers—a resumé of 500 consecutive cases. Proceedings, 1914; 7 (Part 1):17-33.

- Gorgas, Sanitation, 208.

- Conniff ML. Black Labor on a White Canal. Panama, 1904-1981. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1985, 22-44.

- Westerman GW. Los inmigrantes antillanos en Panama (The antillean immigrants in Panama). Panama: La Impresora de La Nación, 1980.

- Lewis LS. The West Indian in Panama: Black Labor in Panama, 1850-1914. Washington, D.C.: University Press of America, Inc., 1980.

- Newton V. The Silver Men. West Indian Labour Migration to Panama 1850-1914. Kingston, Jamaica: Ian Randle Publishers, 1984.

ENRIQUE CHAVES-CARBALLO, MD, is a pediatric neurologist and clinical professor emeritus, Department of History and Philosophy of Medicine, Kansas University Medical Center. He received his medical degree from the University of Oklahoma and trained in pediatrics and neurology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. His main research interest is the medical history of the Panama Canal and he has published several articles and books on tropical diseases, yellow fever, malaria, and Darling.

Summer 2021 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply