Tilman Sauerbruch

Bonn, Germany

|

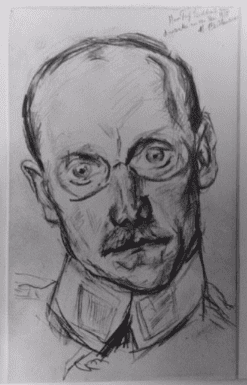

| Fig 1. Portrait-drawing of the of the surgeon Ferdinand Sauerbruch by Max Beckmann 1915 at the frontline during World War I (private collection). |

A photograph of a drawing by Max Beckmann (1884-1950) of the surgeon Ferdinand Sauerbruch (1875-1951) has been hanging in my room since my student days (Fig. 1). At the top right there is a note: “To Prof. Sauerbruch in memory of the May 1915 M. Beckmann.” Beckmann was thirty-one years old at that time, Sauerbruch forty.

I have often asked myself about the creation of this portrait with a uniform collar. Recently in the estate of Ferdinand Sauerbruch I found the document of his leave of absence from his position of surgical director of the Cantonal Hospital Zurich. On June 8, 1914, he was dismissed “for an indefinite period,” with the order to return immediately, “if Switzerland should be drawn into a war.” Sauerbruch then went to the front and became a consulting surgeon with the XV Army Corps in Flanders near Ypres. Also mentioned in the records of the Corps is a “Herr Cassirer,” a member of the Imperial Volunteer Automobile Corps. He was the important art dealer and editor Paul Cassirer (1871-1926), who later had a nervous breakdown and left the front as a pacifist. At that time, he was married to the actress Tilla Durieux (1880-1971). In her memoirs1 she writes:

“A letter came from Paul from Wervik, 15 kilometers from Ypres. He was employed there by the staff and had to bring messages to the front lines. In September he received the Iron Cross, which at that time still really meant a decoration.” And some passages later she wrote: “P.C. told us a lot about Professor Sauerbruch, the later internationally renowned surgeon, with whom he had become great friends. He kept silent about everything else.”

I also found a short note about Beckmann in Sauerbruch’s handwritten diary under the date May 18, 1915.2 It reads:

” . . . Perhaps it is also worth mentioning that the painter Beckmann, the well-known Secessionist, drew me after 2 very short sessions. The picture is very differently judged; I am curious what my wife will say about it. . . .”

Max Beckmann writes around this time, almost a year after the beginning of the war:3

“Wounded were brought in all the time. Some of the poisoned rolled in wild convulsions and gasped heavily. One of them had to be his mouth opened with a mouth lock. I saw fabulous things. In the half-dark dugout semi-dressed men covered with blood, to whom the white bandages were put on. Large and painful in expression. New conceptions of Christ’s flagellation. Then they brought in a first lieutenant, who had just received a severe chest shot. A beautiful face, already half-white with a grayish-pink complexion. He was very calm and very dull.”

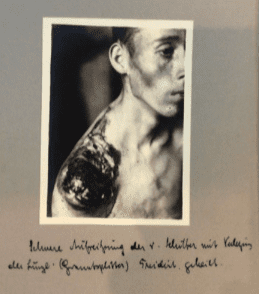

A photograph by Sauerbruch in a military hospital during these months (Fig. 2) evokes this association. Below the picture is his handwritten note: “Severe laceration of the right shoulder with injury to the lung (shrapnel). Revised. Healed.”

During these months, Sauerbruch received a letter from the Directorate of the Education Department of the Canton of Zurich in which he was urged to resume his work as director of the Zurich University Surgical Hospital. Sauerbruch decided to return and took leave of the commanding general Berthold von Deimling (1853-1944) on May 25, 1915.

In his diary of that day he noted “with joy and pride”2 that he had been awarded the Iron Cross, 1st class. This episode reads in the memoirs of Tilla Durieux as follows when she alludes to the melancholy of Paul Cassirer, who was treated by the famous psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler (1857-1939) in Zurich, mediated by Sauerbruch.1

“. . . we met Professor Sauerbruch on the street, who had been with him in Wervik with Deimling’s staff. They had been given the name ‘the crazy guys’. Sauerbruch, one of the most ingenious doctors, behaved in a way that was unacceptable in military terms. He did think highly of elegant impeccable clothing, but it happened to him that he appeared in breeches in his absentmindedness without gaiters, so that his socks and undergarments were visible between boots and trousers. He gave his lad an arbitrary leave of absence and finally, one day, just as arbitrarily, awarded him the Iron Cros. After the brilliant successful healing of Deimling’s wound—at the seat—he was awarded a medal and sent home.”

After taking leave of the general, Sauerbruch writes in his notes:1

“After my return, I then invited the gentlemen once again to a small celebration and it gives credit to the organizational talent of the sergeant with the help of the cook here to arrange a dinner for 30 people for the evening . . . The 99ers played music . . . These are sensations that cannot be forgotten . . . “

And Max Beckmann? He writes on May 24, 1915:3

“Night is once again. Over in the military hospital, they are singing at the farewell party for the chief surgeon with beer. Germany, Germany above all . . . Now and then a cannon thunders from far away. I sit alone as so often. Huh, this infinite space, whose foreground one must fill again and again with something junk, so that one does not see its eerie depth. What would we poor people do, if we would not create for ourselves again and again an idea of fatherland, love, art, and religion, with which we could always cover up the dark hole a little bit. This boundless abandonment in eternity. This being alone. Germany, Germany over a-all . . .We poor children.”

Two feelings about the same evening, even if dated one day apart!

And the life paths of these men?

Paul Cassirer did not recover from his war experiences. His marriage to Tilla Durieux broke up. At the age of 55, he took his own life.

|

| Fig 2. Photograph of a wounded soldier in the military hospital by Ferdinand Sauerbruch with handwritten note: “Severe laceration of the right shoulder with injury of the lung (shrapnel). Revised. Healed.”2 |

Max Beckmann could no longer bear the war. After a mental and physical breakdown, he left the front and was discharged from military service in 1917. The “dark hole” of this time did not leave him anymore. Though awarded the Reichsehrenpreis Deutscher Kunst in 1928, he became an outcast under the Nazi regime. His drawings were declared degenerate art in 1937, he then left Germany and emigrated to the Netherlands. After 1945 he went to the USA, where he died in 1950.4

After his return to Zurich, Sauerbruch experienced conflicts between his German-national outlook on life and his free-minded Swiss medical assistants.5 His response to the sufferings of the front was a first report in the Zurich Medical Clinic in 1915, in which he describes plastic operations to restore the strength of the remaining muscles of the stump of the arm of an amputee for the voluntary movements of a prosthetic hand.6 He publicly declared his support for National Socialism in 1933.7 At the same time he supported persecuted Jewish citizens, such as in the case of the painter Max Liebermann8 and colleagues,9,10,11 and was not aloof from the resistance against the Nazi regime.11,12 Despite his growing inner doubts, however, he tolerated the inhuman dictatorship.7,13

What distinguished him from the sensitivity of the artists Max Beckmann or Paul Cassirer was that destruction of the human body by disease, injury, or war was part of his profession, which he encountered with his surgical skills. After World War II, which he experienced in Berlin, he had six years left. They were overshadowed by old age and late dementia. About this much has been written14—for publicity.

The different characters and paths in life of Beckmann and Sauerbruch are already indicated in their reflections on an evening some hundred years ago. On the one hand, the unconditional artist, who—thirty years old—under the impression of the war intensively sensed the everlasting threat to mankind. And on the other hand, the unconditional surgeon and patriot: a man for whom the empathy towards patients is well documented and who simultaneously tried to fulfill his duties to the “Fatherland” in a society that was to fall into a dark history.

Looking at the portrait, one might think that Beckmann has revealed here the sensitive side of a man he could not or would not always admit to himself—who knows?

References

- Durieux, Tilla. 1954. Eine Tür steht offen. Erinnerungen. Berlin-Grunewald: F.A. Herbig Verlagsbuchhandlung.

- Sauerbruch, Ferdinand, Nachlas 262, Handschriftenabteilung Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Preußischer Kulturbesitz.

- Beckmann, Max.1 984. Briefe im Kriege 1914/1915. München: R. Piper GmbH.

- Reimertz, Stephan. 1995. Max Beckmann. Reinbek: Rowohlt Taschenbuchverlag.

- Dubs-Buchser, Rudolf. 1993. Die Memoiren des Dr. med. Heinrich Freysz. Hintergründe zum Sauerbruch-Skandal Zürich 1915. Zollikon: Kranich-Verlag.

- Sauerbruch, Ferdinand. „Chirurgische Vorarbeit für eine willkürlich bewegliche künstliche Hand“. Medizinische Klinik 41 (1915): 1125.

- Dewey, Marc, Udo Schagen, Wolfgang U Eckart, Eva Schönenberger. „Ernst Ferdinand Sauerbruch and his ambiguous role in the period of National Socialism”. Ann Surg. 244 (2006): 315-21.

- Nationalgalerie Berlin. 1979. Max Liebermann in seiner Zeit. München: Prestel.

- Nissen, Rudolf. 1969. Helle Blätter-dunkle Blätter. Erinnerungen eines Chirurgen. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt.

- Rosenstein, Paul. 1954. Narben bleiben zurück. München: Kindler u. Schiemeyer.

- Michl, Susanne, Thomas Beddies, Christian Bonah (Ed). 2019. Zwangsversetzt vom Elsass an die Berliner Charité. Die Aufzeichnungen der Chirurgen Adolphe Jung, 1940-1945. Basel: Schwabe Verlag Berlin.

- Hassel, Ulrich von. 1946. Vom anderen Deutschland. Aus den nachgelassenen Tagebüchern 1938-1944. Zürich; Freiburg i.Br.: Atlantis Verlag.

- Hahn, Judith, Thomas Schnalke (Ed.) Auf Messers Schneide. 2019. Der Chirurg Ferdinand Sauerbruch. Zwischen Medizin und Mythos. Katalog. Berlin: Berliner Medizinhistorisches Museum der Charité.

- Thorwald, Jürgen. Die Entlassung. 1960. Das Ende des Chirurgen Ferdinand Sauerbruch. München/Zürich: Droemersche Verlagsanstalt Th. Knaur Nachf.

TILMAN SAUERBRUCH, MD, was educated (1966-1971) at the Universities Würzburg, Hamburg, Heidelberg. He was assistant and associate Professor of Internal Medicine at the University of Munich (1984-1992) and full Professor of Medicine at the University of Bonn (1992-2012) and the University of Göttingen (2012-2014). Dr. Sauerbruch has been Professor Emeritus at the University of Bonn since 2014.

Leave a Reply