Kateryna Tsoi

Kharkiv, Ukraine

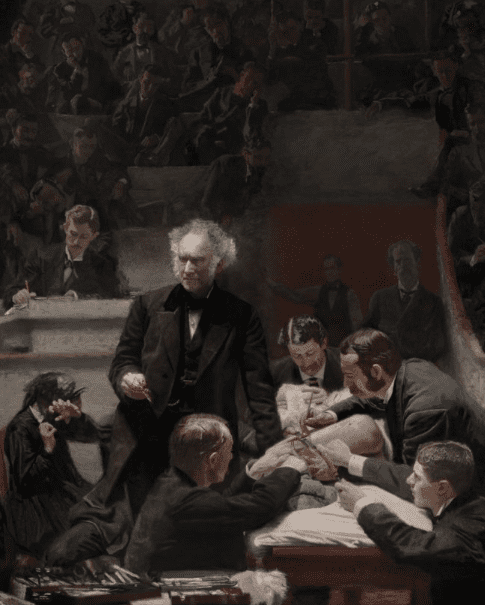

In 1876, the World’s Fair was held outside Europe for the first time, taking place in Philadelphia and coinciding with the centenary of the US Declaration of Independence. Thomas Eakins, not yet a well-known artist, decided to present a large-scale canvas at the exhibition of a subject he knew well. An ardent realist in love with the human form, he had attended anatomy lectures, dissections, and autopsies at Jefferson College of Medicine. His World’s Fair painting was of Samuel Gross performing surgery for students at that College. Gross was one of the best surgeons in the United States and a respected teacher. In The Gross Clinic, Eakins highlights both of these aspects. It is also noteworthy that the author depicted himself sitting near the railing on the right side of the painting with a piece of paper and a pen.

But much to Eakins’ disappointment, The Gross Clinic was not accepted for the main exhibition of the World’s Fair and merely given a place in the medical section. As it turned out, neither critics nor the public were enthusiastic about the painting; instead, they criticized it. They could not look at the realistic portrayal of pain and suffering without concern and horror, finding it offensive. It was considered unacceptable to display a work that was neither entertaining nor uplifting.1

From the perspective of the modern viewer, some of the moments captured on this canvas seem a little implausible. That Gross himself, as well as all his assistants and students, are wearing black street clothes contradicts our image of a physician in a pure white coat.

The concept of a medical uniform has its roots in the fifteenth century. A common myth is that the “costume of the plague doctor” was an invention of the Middle Ages. But in reality, French physician Charles de Lorme developed this outfit during the Early Modern period, which lasted from about the late fifteenth to the early nineteenth century. This black leather suit, consisting of a coat with a hood, was designed to keep the entire body protected. The skin was covered with wax to repel any bodily fluids while visiting the patient. Doctors used these famous “plague suits” and black frock coats from about the fifteenth to the early nineteenth century. They also wore surgical frock coats of dark, predominantly black cloth for operations. They left surgical blood and pus on the frock coat: the dirtier the coat, the more experienced the doctor.2

Another reason for the black costumes of doctors could be that clergymen, the only people who could receive a high-quality education during the Middle Ages, also wore black. Doctors, as a sign of respectability and gentlemanly status, also wore dark, heavy coats. Until about 1900, they wore black to see patients, since medical appointments were considered serious and formal.

In addition, nurses’ uniform were based on the clothing of nuns. To this day, nurses in some countries are called “sister” because of the religious history.3 Long dark tunics were worn with a veil, covering everything except the face.4

The change in attitude about medical uniforms began in the 1870s and 1880s with Koch, Pasteur, and the pioneers of microbiology. They showed that organisms, visible only under the microscope, could introduce infection into the human body. Then Joseph Lister, influenced by Pasteur’s work, developed his antisepsis system to prevent or treat microbial infections. He soaked material in carbolic acid and applied it to an open wound, reducing the rate of infection, gangrene, and other complications. He also argued for the wearing of special suits or gowns during operations and other medical procedures. He believed that if physicians wore white coats, the success rate of surgeries would increase. Such clothing, he argued, had antiseptic properties.5

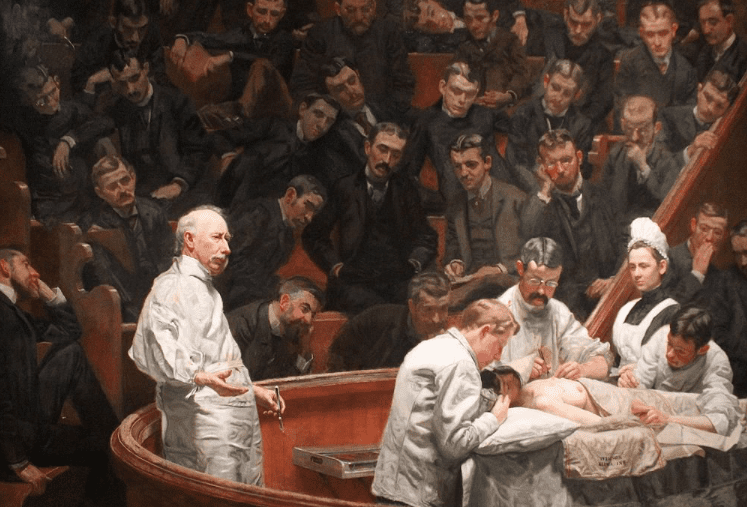

The Agnew Clinic, 1889. By Thomas Eakins. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Via Wikimedia.

His ideas did not immediately gain widespread acceptance. Вut during the 1918 influenza pandemic, the turmoil in hospitals and large number of deaths made it clear that infection control was important. Already in the second half of the nineteenth century, things had begun to look the way we are used to seeing them. Doctors and surgeons had begun to wear white coats instead of frock coats; new doctors were also able to distinguish themselves from barber surgeons and charlatans by raising the standards of the profession.6

Thomas Eakins captured these sweeping changes in his 1889 The Agnew Clinic. This painting depicts David Agnew performing a partial mastectomy in the medical amphitheater at the University of Pennsylvania. But fourteen years after The Gross Clinic, we notice a significant difference in the conduct of surgeries. Agnew is wearing a white coat and the assistants are also dressed in white, which suggests that doctors have new rules of cleanliness.

The decision to portray a half-naked woman in front of a crowd of men, even doctors, in a medical setting, was extraordinary at the time. The painting was once again not accepted for display during exhibitions at the Pennsylvania Academy (1891) and at the New York Society of American Artists (1892).7

While observing and painting these operations, Eakins also documented fundamental changes in the practice of medicine and surgery. Today, thanks to him, we can compare these changes throughout different eras in medicine, as well as admire the realism and truthfulness of his paintings.

References

- Sidelnikova Evgenia “Gross Clinic” https://artchive.ru/thomaseakins/works/287441~Klinika_Grossa.

- Blumhagen DW. The doctor’s white coat: the image of the physician in modern America. Ann Intern Med. 1979;91(1):111-116.

- Shryock RH. The Development of Modern Medicine. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.; 1947:248-272.

- Bates C. A Cultural History of the Nurses`s Uniform. Gatineau: QC: Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation; 2012.

- Khoruzhaya AN Who taught doctors to wash their hands? History of asepsis and antiseptics https://specialviewportal.ru/articles/post454.

- Hardy S, Corones A. Dressed to heal: the changing semiotics of surgical dress. Fash Theory. 2015;20(1):27-49.

- Irina Glick Agnew Clinic: a story about a painting that changed its place of residence https://www.preservarium.com/clinica-agnew/.

KATERYNA TSOI writes articles related to medicine at university and speaks at conferences. One of her favorite subjects was the history of medicine, where she learned many incredible things about how people used to perceive treatment and doctors. She is inspired by how rich and mysterious the inner world of a person is, and wants to know all the secrets of the human body and psyche.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 4 – Fall 2021

Leave a Reply