JMS Pearce

Hull, England

Roald Dahl (1916-1990) (Fig 1) was born in Llandaff, Wales. He was named after Roald Amundsen, the Norwegian explorer who had reached the South Pole just four years earlier. Dahl is known as a popular author of ingenious, irreverent, witty children’s stories and wickedly funny adult books.a He is known for his brilliantly imaginative characters and their pranks, dazzling wordplay, clever imagination, wit, and children’s ability to overcome the cruelties and unfairness of life. But his links to and fascination with medicine are less well known.

After Repton, the public school, he did not attend university but enrolled in the Royal Air Force at the outbreak of World War II. Flying as a fighter pilot, he made an unsuccessful forced landing and his aircraft burst into flames. He sustained serious head, nasal, and back injuries. Months later he was able to re-join his squadron stationed in Greece, became assistant air attaché in Washington, D.C. the following year, and became a close friend of Eleanor Roosevelt. He worked alongside the novelist C.S. Forester, who encouraged him to write about his RAF adventures, which were published by The Saturday Evening Post. At this time, he also worked as an agent for the British MI6 where he encountered Ian Fleming and later adapted his novel You Only Live Twice for the 1967 Bond film.

The measles pamphlet

After numerous dalliances, he married in 1953 the Oscar-winning actress Patricia Neal. They had four children: Olivia, Chantal (Tessa) Sophia, Ophelia Magdalena, and a son Theo. Aged seven, Olivia was to die of measles encephalitis in 1962. Devastated by her death, Roald dedicated James and the Giant Peach (1961) and The BFG [Big Friendly Giant] (1982) to Olivia; he became an ardent campaigner for measles vaccination and in 1986 published a pamphlet “Measles, a Dangerous Illness.”

The dysphasia of Patricia Neal

Further disaster struck when in 1965 his wife Patricia Neal suffered three episodes of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage that were almost fatal. She underwent major brain surgery, but the left side of her brain was damaged. In a coma for three weeks, she was left with a right-sided paralysis (hemiplegia) and with disabling language difficulties in finding words (dysphasia). After three months in hospital, further recovery was deemed improbable. Fearing she would become an “enormous pink cabbage,” Roald imposed an arduous, punishing regime that forced her to ask for things by their correct name or to go without.

With friends and neighbors in Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire, he then set up an intensive six-hours-a-day regime of talking to her, making her try and try again to express herself. Her doctors warned this was too much, but he ignored them. After nearly two years of this slow and relentless treatment, her dysphasia largely recovered. She eventually resumed her acting career, even getting another Oscar nomination. Some of her dysphasic word errors (neologisms) he used in his writings, notably in The BFG.

The film The Patricia Neal Story told the painful and grueling story of how Dahl had bludgeoned his wife into recovery. This “miraculous recovery” attracted much attention and many inquiries for advice from other stroke patients and their families. With the help of a neighbor, Valerie Eaton Griffith, Dahl wrote a guide that was developed into a book. His methods inspired a new movement, which led to the formation of The Stroke Association.

Dahl’s undoubted personal charm was not always in evidence. Fearlessly eschewing convention, he was famous for his infidelity, for insulting people, stirring up quarrels, and often being abusive and anti-Semitic. Even his wife, Patricia Neal, nicknamed him “Roald the Rotten.” After twenty-eight years of turbulent marriage, they were divorced in 1983 and Patricia died in August 2010.

Dahl married Felicity Crosland (nee D’Abreu) in 1983 at Brixton Town Hall. Another link with medicine, she was the daughter of the eminent professor Alphonsus Ligouri D’Abreu, the first professor of cardiothoracic surgery at Birmingham, a man of exceptional elegance, energy, and surgical dexterity.

The Wade-Dahl-Till valve and hydrocephalus

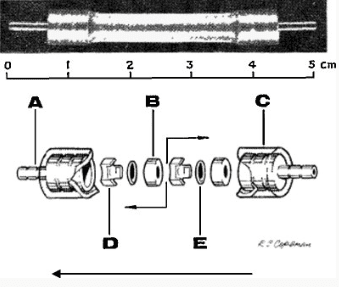

Dahl’s son Theo, when aged four months, developed hydrocephalus after a head injury caused when his pram was struck by a taxi on 5 December 1960. The Holter valve with which he was treated repeatedly became blocked. Dahl therefore set about solving the problem by seeking and coordinating the help of a distinguished neurosurgeon, Kenneth Till of Great Ormond Street Hospital, and Stanley Charles Wade, an expert in precision hydraulic engineering. They developed a mechanism using two metal discs, each in a restrictive housing at the end of a short silicone rubber tube. (Fig 2) Fluid moving under pressure from below pushed the discs against the tube to prevent retrograde flow; pressure from above moved each disc to the “open” position.1

Till reported the invention in The Lancet as characterized by “a low resistance, ease of sterilization, no reflux, robust construction, and negligible risk of blockage.”2 It was highly successful. By the time the device was perfected, Theo had improved and no longer needed the shunt. However, several thousand other children around the world benefited from the WDT valve before medical technology made further advances. The inventors agreed to accept no profits from it. Theo later married and moved to Naples to work with groceries in a local market.

In 1991 Felicity Dahl founded the Roald Dahl Foundation (later renamed Roald Dahl’s Marvellous Children’s Charity) to provide nurses and practical help for seriously ill, disabled children, and for those living in poverty. In 2005 Felicity founded the Roald Dahl Museum and Story Centre in Great Missenden where Roald Dahl spent the last thirty-six years of his life.

Dahl died of acute leukemia complicating myelodysplasia, aged seventy-four, and was buried at St. Peter and St. Paul’s Church in Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire.

“Medical truants” who have left medical practice and found fame in the arts or other endeavors are well known. But typically, Dahl represents perhaps the converse situation: a non-medical man who has made important contributions to medicine: an inverse “medical truant.”

End note

- Some of his best known works are: James and the Giant Peach, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Fantastic Mr Fox, Danny The Champion of the World, Revolting Rhymes, The BFG, Matilda, and Esio Trot.

References

- Buis DR, Mandl ES. Roald Dahl’s contribution to neurosurgery: the Wade-Dahl-Till shunt. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2011;153(2):429-430. doi:10.1007/s00701-010-0834-z

- Till K. A valve for the treatment of hydrocephalus. Lancet. 1964;283:202.

JMS PEARCE, MD, FRCP, is emeritus consultant neurologist in the Department of Neurology at the Hull Royal Infirmary, England.