Lawrence Climo

Lincoln, Massachusetts, United States

I was on my way to an art gallery in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, to view the art of a painter who once lived there, Normal Rockwell. On the way, I stopped first at an exhibit at a local psychiatric hospital where I had once worked. I learned that Rockwell had a history of mental health problems and had sought therapy there. That was long before my time. I had not known that.

Thus, when it came time to visit the Rockwell Art Gallery, I could not help but view his work in this new light. The meaning those works held for me before no longer came to mind, at least, not for the moment. Rockwell’s quest for healing had now become an irresistible distraction and I could not help but try to imagine not only how his mental health issues informed his career but what, deliberately or unconsciously, he might have been trying to express or resolve through the images now on display. What they once meant to me personally was not even on my radar and I knew this would happen when I entered that gallery. My personal reactions to his images would not be playing a part on this tour. I would be too busy walking in his shoes.

That history of Rockwell’s seeking therapy prompted one additional question. Were I the artist, would I really want my personal story linked to my professional work? Would I really want people to know such things about me, even to identify with me and empathize with what I once agonized about? Would they be all the more impressed in the light of my achievements despite that baggage? Would I even care? Would I prefer they simply looked at my art? For me this would be a no-brainer. I would prefer the latter—hearing some variation of, “Your art touches and moves me. Thank you.” Put simply, it is not a reach for me to imagine artists experiencing healing moments knowing their art has been healing for another, that their art touched, enlightened, enriched, or completed someone else’s self-portrait and enabled that other, for an instant, to feel a bit more whole.

But that, of course, had nothing to do with Rockwell’s art. I did not gain something for myself from his private life revelation. Instead, I lost something about myself, an innocent and raw emotional connection to his art.

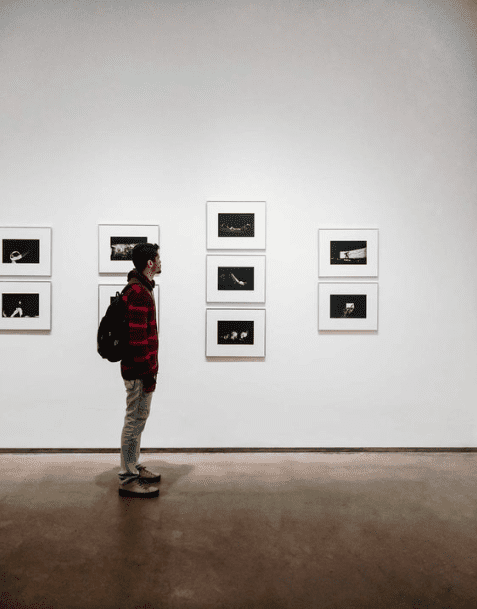

It was my practice on entering an art gallery to read the introduction at the entrance, get a sense of the artist’s personal story, and then listen to headphones, but these weren’t necessarily my lasting memories. What was so often lasting was when I would look about and try to identify the one painting I was most drawn to in that room, the one I favored above the others and for no obvious reason. Then, I would stop and ponder that reason. What was it that drew me to this one and not the others? Often I would have to search hard for the reason that explained the attraction. And, in as much as I had never taken an art appreciation course, this became for me a solitary enlightening experience, this transformation of myself in that gallery into a sort of relief-hitter at bat. I would stand there and look and see and wait for my emotional contact with what was being pitched at me, those paintings. To stay with the baseball metaphor, I was, here, a unique hitter, one that was not focused on understanding what that pitcher was throwing to me, not what the artist was meaning to show, but rather how it was being received by me, the one standing and looking. I, the batter, was the one under scrutiny here, the one who was waiting for the moment a pitch felt right for me. It was not the pitcher, the artist.

Looking back, it was not always easy to find the reasons why a particular picture drew me in and stirred feelings that, on reflection, came to expose facets of myself that had often been forgotten or ignored, sometimes deliberately. That self-centered process involving wordless conversations between parts of myself was a familiar exercise. I should note, this was not because I am a psychiatrist. It was one of the reasons I became a psychiatrist. Learning about others was valuable to my learning about myself. In the art gallery it would awaken in me, if only for a fleeting moment, a more complete or whole me (or “healed” me as some would phrase it). Then, having exposed (or re-exposed) something of myself to myself, and having made room for it in my picture of myself, my personal self-portrait, as it were, I would move on to the next room, the next group of pictures. My takeaway? Visiting art galleries can be enlightening, enriching, and fun without formally studying in classes or from books.

References

- https://learn.canvas.net/courses/24/pages/m1-subjective-and-objective-perspectives

- https://wwweducationalworld.In

LAWRENCE H. CLIMO, M.D., is a Vietnam Vet, board-certified psychiatrist, and writer. He has practiced psychotherapy and psychopharmacology in inpatient and outpatient settings, been a teacher, an administrator, and a forensic consultant. His articles have appeared in professional, academic, and popular journals and magazines and he is the author of three books, The Patient Was Vietcong: An American Doctor in the Vietnamese Health Service, 1966-1967; Psychiatrist on the Road: Encounters in Healing and Healthcare; and Caregiving: Lives Derailed (under the pseudonym Eli Cannon). He is retired and occasionally writes occasional Op-Eds for Psychiatric Times.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 2 – Spring 2022

Leave a Reply