Giovanni Ceccarelli

Roma, Italy

In the late 1940s Elaine de Kooning, wife of one of the most eminent exponents of American abstract expressionism (Willem de Kooning), commented that the whole art world of her time had become alcoholic. Yet even earlier, perhaps always, drinking and drunkenness had attracted the interest of many artists. In a drinking cup (“skyphos“) from the fifth century BCE, a lady in red on a black background is cheerfully drinking.a Drunkenness scenes are also found in the drawings of the altar in Tlaxcalan, pre-Columbian Mexico;1 and Praxiteles (perhaps) in the middle of the fourth century BCE, sculpted a statue of Hermes with Dionysus (the god of wine) as a baby.b The same child Dionysus is shown by Guido Reni as Bacchus, the Roman god of alcohol, drinking from a bottle (Fig.1).2,c Countless other works in classical and religious art are about alcohol, from Noah planting the first vineyard in Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, to the several depictions of the drunkenness of Lot (Gen 19), to the countless Wedding of Cana by Giotto, Duccio, Bosch, Veronese, and others, and to the paintings of Titiand and Rubens.d,e It is more difficult3 to explain the presence in Diego Velazquez The Drunksf of a bright and pensive young Bacchus among Spanish peasants, one with clear signs of rosacea on his nose. A god descended among his acolytes? A mockery of a mythological theme? Or simply a young man disguised as a joke by Bacchus?

But each era had a different incarnation of Bacchus: he became “the green fairy”—absinthe—at the time of the Impressionists and the avant-garde of the early 1900s. Think of van Gogh,g Manet,h Toulouse Lautrec,i and also of Gustave Moreau, who “painted with absinthe” and even invented a cocktail called “Earthquake” (half cognac and half absinthe, served shaken with ice). Think also of Gauguin and Degas, who puts before the glasses two well-known characters from the Paris of those years: the actress Elène Andrée and Marcelin Desboutin (to whom the only portrait of Degas with glasses is due). The greenish color of absinthe adds to many of these paintings an almost bad character, of deliberate perdition towards a world that in turn rejected that painting.

Between the end of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries in England, Bacchus is shown drinking gin, both because new legislation favored distillation to increase the price of wheat, and because—as the sociologist Francis Place later wrote—the poor had only two distractions, sex and gin. William Hogarth, a painter extremely attentive to the customs of his time, showed the consequences of that situation in two famous engravings of 1751: Beer street and Gin Lane for which the term Well Streets was coined. At least in appearance, the first shows its merry and healthy inhabitants drinking beer, the “drink of the ancestors” associated with flourishing industries, lively trade, and social joy; while the second has a population destroyed by the new drink, with infanticide, poverty, hunger, wickedness, and suicide. However, a closer reading of the two engravings shows the link between them, so it is precisely the apparent well-being of the former that is the cause of the poverty of the latter.

A century earlier, in the 1600s, many artists such as Franz Hals and later Jan Steen (son of a brewer) painted drunks and drinkers, scenes filled with a chaos swarming with carousel, cheerful parties, and fat characters such as Falstaff. Perhaps a prototype of this painting can be found in A Dutch Courtyard by Pieter de Hoochj where the man sitting has a mug of beer in his hand and the lady standing is also drinking from a glass. But the masterpiece of this type of painting is The Glass of Wine by Johannes Vermeer,k centered on that transparent glass from which the woman drinks while the man stands ready to fill another one that will make her abandon (he hopes) the temperance painted on the windows. It is not at all certain that these Flemish painters were addicted to alcohol themselves, such as some biographical legends4 and some of their paintingsl,n seem to suggest. Perhaps they were just attentive observers of the surrounding reality.5,6 Certainly other themes (the Nativity, the Annunciation) attracted the attention of art historians more than the licentious scenes of Jan Steen and others; but perhaps it can be said that this type of painting looks much like the themes appearing today on Instagram.

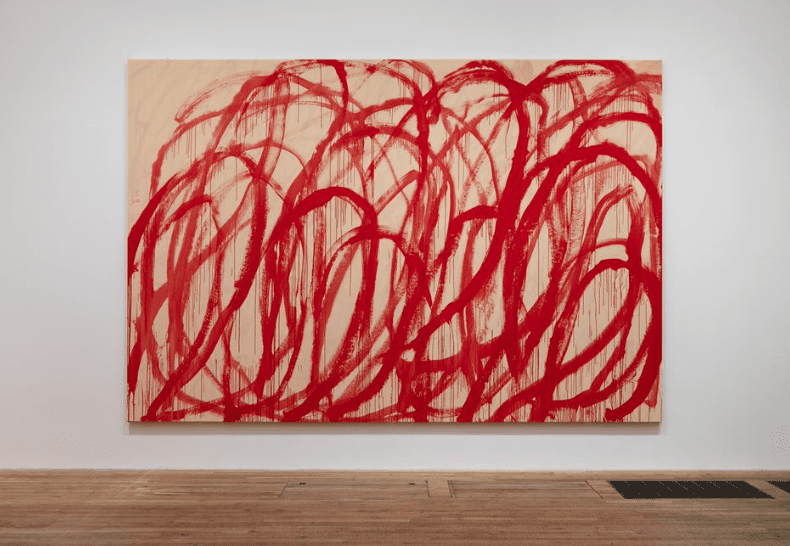

To return to times closer to us, Francis Bacon’s (1909–1992) passion for alcohol is well known, witnessed a few years after his death by his drinking partner, the art historian Michael Peppiatt.7 But the whole “London school” cared about the effects of alcohol, as also seen in the famous portrait of the photographer John Deakin by Lucien Freud (1922–2011), about which it was written that “This image of a man suffering the effects of years of alcohol use would not be out of place in a medical textbook.”8 Often working on the art of the past (famous for his portraits of Pope Innocent X from Velazquez) Bacon builds spaces that are not real but imaginary, inserting into them changing figures caught in tragic hallucinations, spasms that lead to the scream of liberation or defeat, the matter of which nightmares are made; while Freud, in his portraits, gives prominence to a humanity and a reality perhaps less tragic and symbolic, but more real; and both stick to a kind of iconic realism that wanted to speak to a changing world such as the English (and Western) society of the second half of the twentieth century, showing its contradictions and obsessions with escape through alcohol and drugs. But alcohol can also be a stimulating force, as has been said about one of the most recent examples in the series Bacchus (Fig. 2) by an elderly Cy Twomblyn (1928–2011), which one critic described as “a terrible fire springing from the depths of the oceans.”9 In any case, to conclude, art has done nothing but make people see, as Degas said, what cannot be seen because they do not want to see it.

References

- Pohl J.: “Themes of drunkenness, violence and factionalism in Tlaxcalan altar paintings”. RES Anthropology and aesthetics, 1998, 33.

- Kranzler H.R, Hang Zhou H., Kember R.L. et al.: Genome-wide association study of alcohol consumption and use disorder in 274,424 individuals from multiple populations. Nat Commun. 2019, 10(1), 1499-1510.

- Sperling M.: Drinking scenes: the relationship between artists and alcohol. Apollo, International art magazine, 2015, Dec 17.

- Arnold Houbraken: The Great Theatre of Dutch Painters, 1718-1721.

- Seymour Slive: Dutch Painting, 1600-1800 (The Yale University Press Pelican History of Art Series), 1995.

- H. Perry Chapman: Persona and Myth in Houbraken’s life of Jan Steen. The Art Bulletin, 1993, 75 (1), 135-150.

- Peppiatt M.: The Guardian 2015, Sept 2: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/sep/02/francis-bacon-30-years-of-drinking-with-michael-peppiatt-artist.

- Boyce N.: Lucian Freud: in the flesh. Lancet 2012, 379 (9817), 701.

- Bull M., Olivier O.: Cy Twombly, Bacchus. Gagosian gallery ed., 2005.

Specific paintings mentioned in the text

- a. JP Museum, Los Angeles.

- b. Statue of Hermes with Dionysus, Museum of Olympia.

- c. Guido Reni (1575-1642), Bacchus drinking from a bottle, Gemaeldegalerie, Dresden.

- d. Titian (1488-1576), Bacchus and Arianna, 1523, National Gallery London; Baccanali, 1523, now at the Prado.

- e. Rubens (1577-1640), Sileno ebbro 1623, Munich, Alte Pinakothek.

- f. Diego Velazquez (1599-1660), The Drunks (Los burrachos), 1628.

- g. van Gogh, Cafè table avec absinthe, 1887, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

- h. Manet, Le buveur d’absinthe, 1858, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen.

- i. Toulouse Lautrec, Monsieur Boileau au Café, 1893, Cleveland Museum of Art.

- j. Pieter de Hooch, A Dutch Courtyard, 1658, Mauritshuis, The Hague.

- k. Johannes Vermeer, The Glass of Wine, 1659, Gemaelde Galerie, Berlin.

- l. Franz Hals, The Merry Drinker, 1628, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

- m. Jan Steen, The Drinker, 1660, Hermitage.

- n. Cy Twombly, Bacchus, 2005, The Tate, London.

GIOVANNI CECCARELLI, M.D., PhD., (born 1933) is a pediatrician with a degree in Art History (Sapienza, Rome University). He specialized at University of Pavia where he obtained (1968) a “Libera docenza” (free teaching University degree) and now lives in Rome. In 2010 (at 77 years old) he obtained (magna cum laude) a degree in Art History at Sapienza, University of Roma. Over the last few years he has published some books: Fading away, painting the farewell, 2013 (on Ferdinand Hodler and his lover Valentine Godé Darel; preface by G.R. Burgio and V. Nesi) and Malattie di artisti (in English: Diseases of artists), 2017, preface by J. Nigro Covre and F. Pierangeli. He is a widower, has two children, five grandchildren, and a great-granddaughter, Ludovica.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 4 – Fall 2022

Leave a Reply