J.T.H. Connor

St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada

In 1927 the Davis & Geck (DG) company commissioned artist Lejaren à Hiller to promote its surgical sutures. Hiller’s subsequent advertising campaign of modern art photographs was distributed to doctors across the United States and Canada during the 1920s to 1940s in simulated leather portfolios titled Sutures in Ancient Surgery in gilt script. A book of collated photographs also appeared.1 Long-time DG employee Charles Riall mused that “there probably are thousands [of images] still on doctors [sic] walls.”2 The Sutures portfolio still circulates in the antiquarian book market. Another gauge of its cultural value is its acquisition by medical museums. Significantly, the later ubiquitous pharmaceutical company Parke-Davis’ promotional series of Great Moments in Medicine owes its inception to Sutures.3 A donation of a Sutures portfolio on behalf of a deceased doctor, along with his microscope and a 1936 graduation photograph of his tuxedo-clad Nu Sigma chapter brothers of the Phi Chi medical fraternity, prompted this discussion. It is telling that Sutures made it to the North Atlantic island outpost of Newfoundland and was retained as a treasured personal possession.4

Lejaren à Hiller (1880-1969), born in Milwaukee as John Arthur Hiller, apprenticed at the age of fifteen with the American Fine Art Company, then later with the Gugler Lithographic Company. In 1900 he attended the School of the Chicago Art Institute, training in commercial and classical fine arts. Hiller’s extra-curricular activities included theatrical stage design and lighting. He also engaged in photography, shooting portraits, groups, and artists’ models. The Art Institute promoted photography as a novel, modern art form by sponsoring exhibitions of photographers, including Alfred Stieglitz. One visual arts authority concluded that by 1904, Hiller was already “experimenting” with techniques that would become his hallmarks, such as using soft-focus lenses and hand-painting on photographic prints.

Hiller worked as a commercial artist and photographer. In 1907 he settled permanently in New York City. He underwent Frenchification (after previously living in Paris) to become Lejaren à Hiller, based on his nickname of Jaren and his middle initial. He also produced covers for Cosmopolitan and Harper’s Bazaar magazines. Around 1913 photography became his medium when he illustrated a short story that was stylistically original through superimposition of a staged studio photograph of characters portrayed on another photograph of an outdoor street scene. The image was enhanced by a chiaroscuro effect, making it dark and moody.

Magazines eagerly sought Hiller’s innovative skills and he quickly became a successful photographic artist-illustrator.5 Soon acknowledged as “dean of American illustrative photographers,” he became the highest-paid illustrator in the United States. A 1986 Hiller retrospective exhibit described Hiller as “one of the forgotten masters” of twentieth-century photography. Hiller’s works were “so well known in the magazine-reading public of the 1920’s, 30’s, and 40’s, that they will undoubtedly be remembered by middle-aged and elderly visitors” to the exhibit. Central to Hiller’s work were tableaux vivants—staged scenes involving many human models in stylized and dramatic historico-theatrical poses, while using dramatic lighting and innovative camera angles: “By and large . . Hiller’s constructed tableaux are still remarkably convincing even when seen in the large original prints of the exhibition rather than the smaller half-tone reproductions for which they were intended.”6

Hiller’s use of tableaux vivants aimed to sell products, for increasingly he moved from story illustration to creating arresting images for advertisers—yet another emerging, modern arts field that Hiller advanced. One historian coined the term social tableaux, derived from tableaux vivants, which are the photographic components of ads that began to appear in the 1920s depicting a scenario imparting an emotional response in the viewer. Even if the accompanying text or copy was not read, there was a story or feeling imbedded in the photograph that engaged the viewer. Visual clichés evoking family values, comfort, security, or social identity became conventional.

Today the novelty of this emotive advertising may not be fully appreciated. Briefly, before 1920, ads were text-based (perhaps with a simple graphic of the product) grounded in logic and facts. The appeal to the consumer was rational, not emotional.7 Hiller’s experience as a magazine illustrator; his use of innovative photographic techniques; and his understanding of how tableaux vivants were created, staged, and how the models in them need to be directed, all acted to his advantage. As another historian noted, Hiller’s style was fundamentally pictorialist. Adherents of this early twentieth-century popular movement believed the camera and photography were artists’ tools to be used to break away from the “tyranny of fact.” Further, the “preference for classical tableaux . . . pushed the camera image beyond the mechanical recording of social fact to express intimacy, ecstasy, ambiguity, and revelation . . .” One major outcome of this was the blurring of boundaries and motives: “[T]he line between fiction and advertising, between the material and the nonmaterial worlds, were growing profitably indistinct.”8

Hiller’s genius lay in combining modern arts photography and advertising; his DG-sponsored Sutures in Ancient Surgery series epitomized such skills. DG founders Charles Davis and Fred Geck partnered in 1909 in New York City to become the second-largest manufacturer of pre-sterilized, pre-packed sutures. This was clinically time-saving and economical. Before Sutures, company advertisements were conventional fact- and figure-laden, appealing to a logical response from potential buyers. Copy consisted of catalog numbers, product description, cost and ordering information, an account of manufacturing processes, and an explanation of technical aspects; illustrations were product drawings, along with graphs or charts. Typical bland captions included: “A wholesale discount of 25% is accorded hospitals and surgeons on any quantity of sutures down to one gross.”9 The Sutures campaign substituted dry facts about sutures with ads featuring Hiller’s striking photographs and copy explaining the scene alluding to suturing techniques in the era depicted.

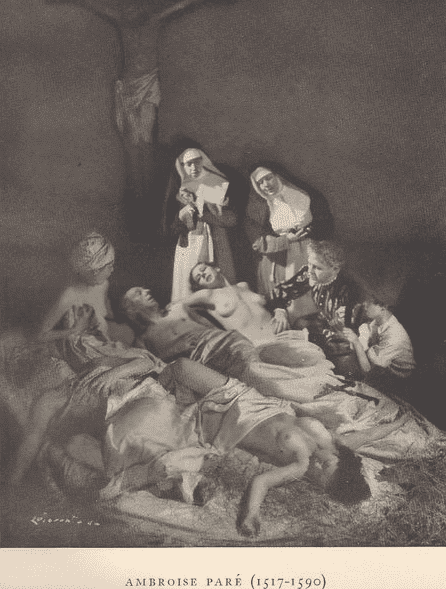

The eighty-three images comprising Sutures demonstrate a range from prehistoric times, classical Greece and Rome, the Middle Ages, and through to the nineteenth century. Portrayed were: Albucasis, Avicenna, Celsus, Fallopius, Fabricius, Galen, Harvey, Hunter, Rhazes, and Vesalius, all explained within anatomy, physiology, pathology, and medical practice. Occasionally, ads might address non-Western cultures such the Aztec empire, Egypt, and India. The bias of Sutures towards great, dead white men, their good deeds, along with the ineluctable progress of surgery may not resonate with today’s social medical history, but it reflected the aims and standards of its era. Occasionally, women featured in Sutures—but from a “politically correct” perspective, perhaps problematically. Dame Trotula appeared in her own medical right as the medieval “matron of Salerno” owing to her contributions to obstetrics and gynecology, yet women (while admittedly only a small percentage of all characters portrayed) in Sutures were typically wholly naked or bare-breasted—and perhaps for their predominantly male medical audience—titillating. Inaugural issues of Playboy magazine featured Hiller’s work;10 recently his representations have been identified as “doctor porn” and “slightly creepy.”11

More important was the messaging to doctors: Medicine circa 1930 epitomized the new, the advanced, and the modern, but also the realization that it had a primitive past. The efflorescence of the field of medical history around 1930 was signaled by an upsurge of books, along with other lasting academic milestones, and contextualized the reason that “ancient surgery” was salient in the series title. The use of light and dark in images invoked mindsets of good/progress and evil/primitive: binary opposites existed in tension. The audience for Sutures—medical doctors—represented the progressive, while what was portrayed, even when the scene was an advancement, was the primitive. Hiller’s use of costume and scenery ensured the vista was disconnected from the modern present. But Hiller was an artist, not a historian, so who formulated the ad ideas? Enter Samuel Harvey (1886-1953), whom Hiller retained as consultant. Harvey, a 1907 Yale MD graduate, trained under neurosurgeon and Osler historian Harvey Cushing. He edited the Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine; his interest in medical history intensified upon joining Yale’s Department of History of Medicine in 1951. American medical history journals eulogized him and Yale’s Samuel Clark Harvey Memorial Lecture commemorates him.12

Sutures, by linking ancient surgery with modern arts, was a modern advertising medium connecting seller and buyer; the images also fused historical content with various visual art forms. A 1939 Life magazine feature of Hiller’s work noted how “medical men repeatedly mistake the photographs for fine reproductions of old masterpieces which never existed.”13 Overall sales numbers are not known, but the long-running striking Sutures campaign demonstrates that DG’s investment was worthwhile.

Notes

- Lejaren à Hiller, Surgery Through the Ages: A Pictorial Chronicle (New York: Hastings House, 1944).

- Letter from Charles T. Riall dated 12 June 1997 contained in Davis & Geck company archival material supplied to the author courtesy of University of Connecticut Library; see https://archivessearch.lib.uconn.edu/repositories/2/archival_objects/40786

- Jacalyn Duffin and Alison Li, “Great Moments: Parke, Davis and Company and the Creation of Medical Art,” Isis 86 (1995): 1-29; and, Jonathan Metzl and Joel Howell, “Making History: Lessons from the Great Moments Series of Pharmaceutical Advertisements,” Academic Medicine 79 (2004): 1027-32.

- The original owner was Dr Harry D. Roberts; see http://www.cmaj.ca/content/cmaj/171/11/1419.full.pdf I am grateful to the Hon. Edward Roberts for this donation.

- Doug Manchee, Sutures and Spirits: The Photographic Legacy of Lejaren à Hiller (Rochester, NY: RIT Press, 2018), passim; Elspeth H. Brown, “Rationalizing Consumption: Lejaren à Hiller and the Origins of American Advertising Photography, 1913-1924,” Enterprise & Society 1 (December 2000): 715-38, see esp.725-7; also Brown, The Corporate Eye: Photography and the Rationalization of American Corporate Culture, 1884-1929 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005); Robert E. Skinner, “Photography, Advertising, and the History of Medicine: Notes on the Medico-historical Art of Lejaren Á Hiller,” Watermark 6 (Oct 1982-Jan 1983): 11-12; Lejaren à Hiller: A Half Century of Photographic Illustration (Visual Studies Workshop: Rochester, NY [1986]); on the VSW, see http://www.vsw.org/about/

- Gene Thornton, “When Tableaux Vivants Flowered in the Magazines,” New York Times, 2 March, 1986, H29.

- Roland Marchand, Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity, 1920-1940 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), ch. 6.

- Brown, “Rationalizing Consumption,” 728-9.

- Davis & Geck advertisement for “Surgical Sutures Claustro-Thermal Catgut” in Modern Hospital (May 1922).

- David John Lambkin, “Playboy’s First Year: a Rhetorical Construction of Masculine Sexuality” (1999). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses, 111 https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6997

- Bert Hansen, “Medical History’s Moment in Art Photography (1920-1950): How Lejaren à Hiller and Valentino Sarra Created a Fashion for Scenes of Early Surgery,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 72 (2017): 381-421.

- See Skinner, “Photography, Advertising, and the History of Medicine,” where Skinner cites a personal communication dated 22 November 1982 by Charles Riall regarding Harvey’s role. For Harvey’s life and activities, see: Elizabeth H. Thomson, “Samuel Clark Harvey—Medical Historian, 1886-1953,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 9 (1954): 1-8; John F. Fulton, “Samuel Clark Harvey (1886-1953),” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 28 (1954): 275; Max Taffel, “Samuel Clark Harvey, 1886-1953,” Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 26 (1953): 1-7; and Alfred Blalock, “Samuel Clark Harvey: A Tribute from a Fellow Surgeon,” Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 23 (1951): 522; and http://surgery.yale.edu/education/program/Harvey%20Lecture%207.15_271032_153_4291_v1.pdf

- “Speaking of Pictures…These are Milestones in the History of Surgery,” Life, 23 January 1939, 6.

J.T.H. CONNOR has published extensively on the history of science, technology, and medicine in nineteenth- and twentieth-century North America; topics embraced include surgical, military, rural, and hospital medical history, along with the history of medical museums, eugenics, and alternative medicine. He teaches both medical learners and history students, for which he has received several awards. He was editor of the Canadian Bulletin Medical History, and now co-edits the McGill-Queen’s University Press series in medical history, which has published approximately 60 volumes to date.

Leave a Reply