Jacob Appel

New York, New York, United States

Few subjects have attracted as much attention from medical historians, both well-founded and speculative, as the health of United States presidents. Considerable debate exists over the extent of impairment caused by Lincoln’s bouts of melancholia,1 Grant’s alcoholism,2 Wilson’s stroke,3 and Coolidge’s depression4—to name only those chief executives from the remote past. But has a president ever been so psychiatrically ill that he could not carry out the duties of office? The strongest candidate for this dubious honor is Franklin Piece (1804–1869), whose bungling one term from 1853 to 1857 steered the nation on a course toward disunion. While much has been written about Pierce’s despair and inebriation—which would likely meet the DSM-V criteria for either Major Depressive Disorder or Substance Induced Depressive Disorder5—less attention has been devoted to two disturbing and unique aspects of this crisis: namely, how close it brought the nation to a constitutional crisis of succession, and how it indirectly led the federal government to turn its back on thousands of other mentally ill citizens.

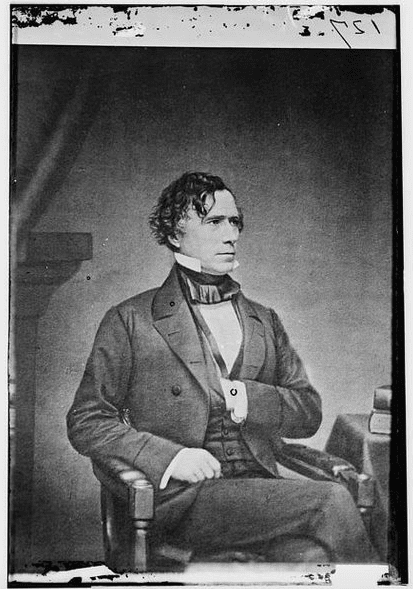

Pierce—who pronounced his own name “Purse”6—was a “dark horse” Democratic nominee for the White House whose landslide victory over Whig candidate Winfield Scott occurred against the backdrop of rising tensions over slavery. The youngest president at the time of his inauguration at age forty-nine, and widely regarded by contemporaries as good-looking and genial,7 “Handsome Frank” Pierce was a patrician New Englander with an “irresistible . . . graciousness of manner”8 and pro-Southern leanings who had served in both houses of Congress and as a general during the War with Mexico. In an 1852 biography, his close friend Nathaniel Hawthorne went out of his way to praise Pierce’s resilience, describing him in his youth as a “young man vigorous enough to overcome the momentary depression.”9

While his opponents derided him as the “hero of a well-fought bottle,” hinting at difficulties with alcohol consumption during his years in the Senate, it is hard to discern the extent of his drinking in an era when liquor flowed much more freely than today, especially in politics,10 and when such accusations proved all too common. Pierce did draw negative attention for his involvement with two other congressmen in an inebriated brawl at a Washington theater in 1836.11

And there are other signs that Pierce’s drinking may have exceeded contemporary norms: Jonathan Davidson and Kathryn Connor have noted that “in the 1840s, Pierce had declined the opportunity to stand as governor of his state and also an invitation to serve as President Polk’s attorney general, because of fear of the social drinking that was part and parcel of political life.”12 However, this reluctance must be viewed in light of the concerns of Pierce’s wife, Jane. Mrs. Pierce, a teetotaler, was not publicly opposed to alcohol consumption (unlike her recent predecessor, the devoutly Methodist Sarah Polk), but did object to her husband’s drinking and often pressured him to swear off alcohol—initially, with intermittent success. Of note, despite Hawthorne’s predictions, Davidson and Connor have also documented that Pierce suffered a serious bout of depression during his twenties.13

The President-elect who boarded the noon Boston & Maine train at Andover, Massachusetts, on January 6, 1853, bound for Concord with his wife and eleven-year-old son, might have been able to hold his diatheses toward sorrow and spirits in check.14 The family was returning home from the funeral of Mrs. Pierce’s uncle. Then a second tragedy struck: a broken axle sent their train car careening down a twenty-foot embankment, killing the child. “The little boy’s brains were dashed out,” wrote the New York Daily Times. “General Piece took him up; he did not think the poor little fellow was dead until he took off his cap.” 15 The death of Pierce’s only surviving son—two had died earlier in childhood—left the President-elect “greatly prostrated by melancholy.”16 It was a heartbreak from which neither he nor the First Lady would recover.

Mrs. Pierce suffered a severe breakdown that saw her largely abandon the duties of her office for twenty-one months while speaking and writing guilt-ridden letters to her deceased son.17 She wore the black of mourning and became known as “the shadow in the White House.”18 When she finally reemerged in 1855, she was “hardly a cheerful sight” and “her woebegone face banished all animation in others.”19 Meanwhile, President Pierce descended into depression and heavy drinking. He began his inaugural address with the lament that, “It is a relief that no heart but my own can know the personal regret and bitter sorrow over which I have been borne to a position so suitable for others rather than desirable for myself.”20 By the time he was denied renomination four years later, he was alleged to have declared, “There’s nothing left to do but get drunk.”21 This quotation, like the story that Pierce ran over a woman with a carriage while inebriated, is likely apocryphal—but that it has been widely accepted offers good insight into the state of the man’s health. His drinking worsened after his presidency and he succumbed to cirrhosis in 1869.

Why does this matter? While much has been written to criticize the Pierce administration’s general ineptitude and pro-Southern leanings—his term saw the passage of the pro-slavery Kansas–Nebraska Act and enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act—two specific implications of Pierce’s mental decline are largely overlooked.

The death of Vice President William King on April 18, 1853 from tuberculosis left Pierce without a vice president for nearly his entire term. This raised two complex issues related to presidential succession. First, no process existed for the removal of an impaired president who refused or proved unable to recognize his own impairment; in fact, at the objection of John Dickinson, the Framers of the Constitution had rejected creating such a procedure. Second, the Presidential Succession Act of 1792 provided for the president pro tempore to serve as acting president if the offices of both president and vice president were vacated, until a new election could be held. Had Pierce been forced from office, a replacement election would have been required and the victors elected to full four-year terms.22 The Constitutional legitimacy of such a process was, and remains, unclear—and its invocation would have provoked a crisis.

Pierce’s term was also notable for his decision to veto the Land-Grant Bill for Indigent Insane Persons in 1854. The legislation, which would have distributed federal lands to the states for the support of the indigent mentally ill, was spearheaded by reformer Dorothea Dix and passed the Senate by a vote of 25 to 12 with considerable support from within Pierce’s own party.23 His veto, on narrow constitutional grounds, came as a surprise to reformers. They blasted the decision as “deliberate callousness” by a president who opposed “sentimental legislation” and described the “veto [as] more of an individual than of a great public official.”24 One cannot help but wonder to what degree the president’s own bouts with mental illness, and his desire to project psychological strength, shaped this unpopular decision. The result proved the last serious effort to address mental health at the federal level until the passage of the National Mental Health Act in 1946.25

References

- Shenk JW. Lincoln’s Great Depression. The Atlantic. Oct 2005.

- Shafer, RG. Trump called Ulysses S. Grant an alcoholic. Here’s what historians say about that. Washington Post. Oct. 16, 2018.

- Menger RP, Storey CM, Guthikonda B, et al. Woodrow Wilson’s hidden stroke of 1919: the impact of patient-physician confidentiality on United States foreign policy. Neurosurg Focus. 2015 Jul;39(1):E6.

- Beatty, J. President Coolidge’s Burden. The Atlantic. Dec 2003.

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

- Kingsburg AB. Changes in Spoken English. The New Science Review. 1895:1-2.

- Forney JW. Anecdotes of Public Men. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1873, P. 418.

- Boulard G. The Expatriation of Franklin Pierce: The Story of a President and the Civil War. iUniverse, 2006.

- Hawthorne N. Life of Franklin Pierce. Boston: Ticknor, Reed and Fields; 1852.

- Chu JM (2000) The Demon and Daniel Webster: Drinking in the antebellum senate. 2000;1:2, 97-104,

- Boulard G. The Expatriation of Franklin Pierce: The Story of a President and the Civil War. iUniverse, 2006.

- Davidson JR, Connor KM. The impairment of Presidents Pierce and Coolidge after traumatic bereavement. Compr Psychiatry. 2008 Jul-Aug;49(4):413-9.

- Davidson JR, Connor KM. The impairment of Presidents Pierce and Coolidge after traumatic bereavement. Compr Psychiatry. 2008 Jul-Aug;49(4):413-9.

- Dreadful Railroad Accident: Loss Of Life Narrow Escape Of Gen. Pierce. New York Daily Tribune. Jan 7 1853, p.5.

- New York Daily Times, Jan 7, 1853 p. 1.

- New York Daily Times, Jan 12, 1853 p. 1.

- Wallace I, Wallechinsky D, Wallace A. The Phantom First Lady. The Hartford Courant. Oct 4 1981, P. K2

- Winn W. Precedent Is What First Ladies Make It: Mamie, Others Indebted to Eliza Monroe. Chicago Daily Tribune. Jan 19 1957. p 11.

- Wallace I, Wallechinsky D, Wallace A. The Phantom First Lady. The Hartford Courant. Oct 4 1981, P. K2

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. March 5, 1853. p. 4

- Blumenthal S. All the Powers of Earth. New York: Simon & Schuster; 2020. P 8.

- Hamlin CS. The Presidential Succession Act of 1886 Harvard Law Review. 1905:18 (3):182–195.

- Manning SW. The Tragedy of the Ten-Million-Acre Bill. Social Service Review. 1962:36(1):44.

- Manning SW. The Tragedy of the Ten-Million-Acre Bill. Social Service Review. 1962:36(1):44.

- Rusk HA. Century-Old Crusade Leads To Mental Health Institute. New York Times. Apr 24, 1949.

JACOB M. APPEL, MD, JD, MPH, is Director of Ethics Education in Psychiatry and Assistant Director for the Academy of Medicine & the Humanities at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. His latest book is a compendium of ethical dilemmas, Who Says You’re Dead? More at: www.jacobmappel.com

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 15, Issue 1 – Winter 2023

Leave a Reply