Pavane Gorrepati

Iowa City, Iowa, United States

The fight against malaria has largely been successful because of modern scientific advances, but during World War II the fight was supplemented by propaganda posters warning soldiers about malaria just as they were warmed against venereal diseases. Everyone was expected to aid the war effort—women to plant victory gardens to make rations go farther and consumers to stop using supplies such as gas and rubber.1 The responsibility to support the Allied forces was personal, and this included the soldiers. They had to fight the enemy but also take care of their health in order to win the war, as expressed in the first Malaria Training Manual:

Experience has shown that organized and properly directed preventative measures against malaria in military forces in the South Pacific Area, will check the disease to a degree which will permit the successful accomplishment of military operations. Failure to take steps, however, will result in an enormous degree of sickness and loss of man days, as might as well be expected in the conduct of war on some of the most malarious islands in the world.2

The manual was published in 1944 and disseminated to troops as posters and calendars. It emphasized the necessity to take atabrine and be aware of their personal health. It used humor, sex, and appealed to national pride through print media.

Such education was particularly important when medical supplies were in short supply. Malaria had not been particularly prevalent in the United States in the 1930s, except in parts of the South,3 and the thousands of nurses and doctors treating soldiers during war considered it to be a tropical disease. Soldiers had to be taught about prevention, symptoms, and treatment, which the military did through educational programs and posters. General Douglas McArthur himself emphasized the importance of controlling malaria: “. . . it would be a very long war indeed if . . . he must count on a second division in [the] hospital with acute malaria, and a third division in a convalescent depot with relapsing malaria.”4

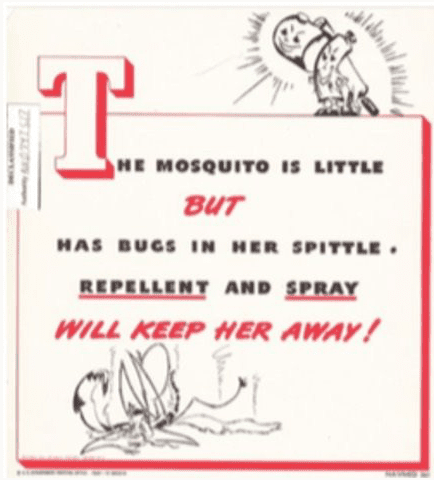

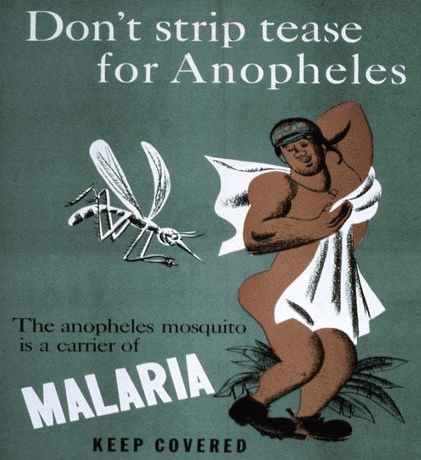

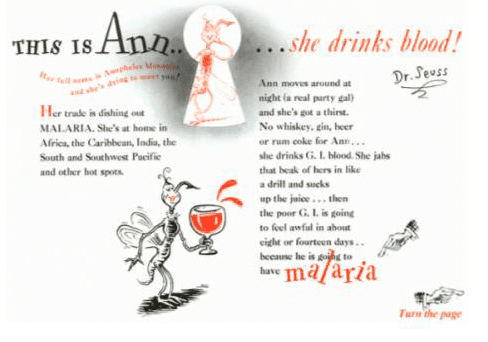

Early posters and educational materials were meant to inform soldiers to be vigilant about their health. Later the tone of the messages began to shift from solely instructive messages to more sexualized slogans. Posters released in 1944 told how repellents and sprays were effective in keeping mosquitos away.5 One poster with the caption “Don’t strip tease for Anopheles” advised soldiers to keep covered as a preventive measure.6 Theodore Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, also educated soldiers by means of a published booklet.7 His story follows Ann, an anopheles mosquito, and tells soldiers how to protect themselves, emphasizing that “the real job is up to you.”8 From sleeping under bed nets, to using repellents, to not swimming or bathing at night, Geisel covered all the major precautionary actions that needed to be taken. The booklet included the characteristic humorous drawings of Dr. Seuss and provided an amusing way to deliver serious information.

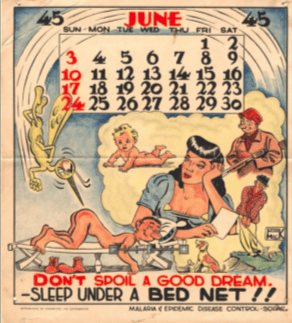

By 1945 the military started printing calendars portraying each month as a different anti-malaria pin-up model. For example, the May 1945 poster featured a woman in a negligee admiring a military man and seductively running her hands through her hair with the slogans: “Spray your quarters – at night and in the morning,” “No swimming – after sunset,” and “If you don’t give a darn about yourself – do it for her!”9 Soldiers were given an enticing reason to stay vigilant about malaria and the military protocols. The June 1945 poster featured a young soldier sleeping and dreaming of all the comforts of home—his dog, his baby, his hobbies, golf and hunting, and most importantly, his girl back home.10 As he sleeps, dreaming away the horrors and stresses of war, an anopheles mosquito flies down to attack him on his rear with the caption, “Don’t spoil a good dream – sleep under a bed net!!”11 These images showed a shift in messaging as the military understood that providing information would only go so far and that ulterior motivations were needed. By using alluring images, soldiers were more likely to look at the posters and take the messages to heart.

Many of the print materials drew on the themes of humor, sex, and nationalistic pride. Far away from their loved ones and the comforts of their country, military men were able to seek refuge and humor in these posters. Through the use of propaganda and informative messages, the military was able to reinforce the message of a soldier’s personal responsibility to keep healthy in order to win the war. Some of the print materials used sexualized images of women to convince the soldiers to follow the malaria protocol if not for their own health then at the very least to “do it for her!” Soldiers could enjoy a laugh, while briefly forgetting the horrors of war, and also strengthen their knowledge of malaria protocols.

Appendix A

References

- Martin Gilbert, The Second World War: A Complete History (London: Phoenix, 2009), 231.

- Malaria Training Manual No. 1, 1944, A11 (22-1) Entomology — Disease Vectors, Pacific Island, Records Relating to Malaria and Epidemiological Disease Control, RG 313, U.S. National Library of Medicine Archive.

- Margaret Humphreys, Malaria: Poverty, Race, and Public Health in the United States (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001), 124.

- Ibid, 25.

- See Appendix A, Figure 1. Color Poster No. C01320, “The Mosquito Is Little,” 1944, Archives of U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- See Appendix A, Figure 2. Color Poster No. C01770, “Don’t Strip Tease for Anopheles,” 1944, Archives of U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- See Appendix A, Figure 3 and Appendix B Color Poster No. A026641, “This is Ann…she drinks blood!,” 1943, Archives of U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Ibid.

- See Appendix A, Figure 4. Color Poster No. C06235, “May: If You Don’t Give a Darn About Yourself,” 1945, Archives of U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- See Appendix A, Figure 5. Color Poster No. C06236, “June: Don’t Spoil A Good Dream,” 1945, Archives of U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Ibid.

PAVANE L. GORREPATI is currently a third-year medical student at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine. She graduated with distinction from Yale University in 2016 with a degree in the History of Science, Medicine, and Public Health.