Kristin Krumenacker

Huntington, New York, United States

|

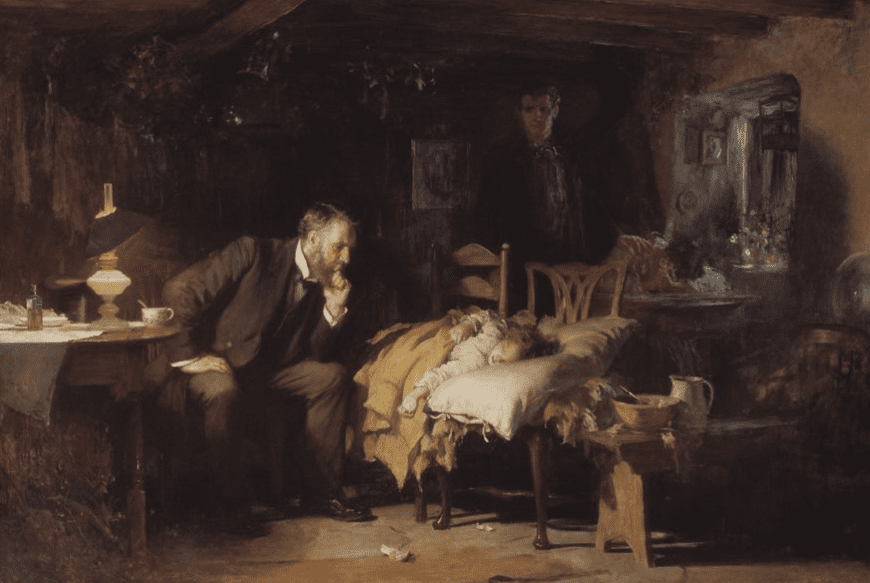

| The Doctor, 1891, Sir Luke Fildes.© The Tate Britain. CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported). Source |

Medical schools have increasingly included the humanities in their curricula, hoping to encourage empathy and compassion in their students. The effects of teaching the humanities is not limited to the student but can benefit the patient as well. In an era where more and more importance is placed on diagnostic testing, observational and physical exam skills take a back seat to laboratory data.1 However, the gulf between sight and observation is wide, and the price of missed observations has serious consequences for patients.2,3 Training in fine arts and visual observation has been shown to enhance observational skills,4,5 and this effect would be especially relevant in radiology, which relies heavily on the close examination and interpretation of visual media.

The I Spy series of books flourished amongst children for the same reason that a radiologist’s job is so difficult: it is often challenging and time-consuming to scour a complex image for discrete details, especially without experience. Visual thinking strategy is one approach to art observation that is based on answering three questions: 1) What is going on in this picture? 2) What do you see that makes you think that? and 3) What more can you find?3 Even with such an approach, however, my own experience in an Art & Observation course in medical school demonstrated how easy it can be to misinterpret an image or miss crucial details. The instructor showed the class a painting of a coastline with a farmer plowing his field in the foreground. He then asked us to describe the narrative of the painting. We spent a minute describing the peaceful and pastoral elements of the image, satisfied that the narrative of the painting was one of humble life on a coastal farm, until someone noticed a person’s legs flailing in the water. The painting was Landscape with the Fall of Icarus by Pieter Bruegel the Elder,4 yet we had nearly failed to notice the titular character. Similarly, while examining The Doctor by Luke Fildes,5 our instructor asked us how many people the scene contained. The candlelight prominently lit the faces of the doctor and the child, leading some students to overlook the shadowed face of the father in the background. Even more students failed to pick out the mother, who was both veiled in shadow and had her head lowered in grief.

Much like failing to recognize the dire situation of Icarus in an otherwise peaceful painting, radiologists might fail to notice a subtle but important abnormality in an otherwise normal image. Most diagnostic errors in radiology are perceptive rather than interpretive,6 meaning that abnormalities frequently escape initial detection. A similar difficulty is that of search satisfaction, or the premature termination of a detailed search after one abnormality or explanation has been found,7 much like my satisfaction that there were three people in The Doctor until someone pointed out the existence of a fourth.

The idea of using observation training to hone radiologic skill is not new. Braverman describes a 1979 study by Adrian-Harris initially intended to examine cognitive thinking. The experiment required participants to identify a single vowel target in a string of 250 consonants.8 Adrian-Harris realized that one participant, a radiologist by trade, could identify the target nine times faster than other participants. He decided to focus a study on radiologists and their ability to correctly classify X-rays as normal, abnormal, or possibly abnormal. He gave these 250-character target search exercises to a group of radiologists, while a control group of radiologists continued their usual work. Each group was later shown identical X-ray images and asked to classify the image as normal, abnormal, or possibly abnormal. The group of radiologists that did the visual exercise improved the accuracy of their X-ray interpretation from 49% to 76%, whereas the control group’s accuracy did not change.9

Visual art or observation training has been increasingly implemented in radiology residency programs, but it is far from a widespread practice despite its potential benefits. On the first day of residency in 2017, the Yale radiology residency program brought fifteen residents to the Yale Center for British Art.10 They received detailed instruction from museum employees experienced in teaching fine art perception, which included recording a list of perceived details, communicating these observed details to the group, and teacher-guided expansion of perception to extract additional details. The exercise culminated in an interpretative discussion in which the instructor asked the residents to state the larger meaning or story the painting conveyed. To assess the residents’ progress, the trainees were asked to identify abnormalities on a file of radiographs both before and after the exercise. The results revealed a statistically significant increase in their ability to correctly identify abnormalities, and each of the fifteen residents showed individual improvement in accuracy after the exercise.11 Similar exercises were done with radiology residents at the University of Massachusetts, which again showed that residents who underwent a structured art observation exercise were better able to describe radiographic findings.12

The visual arts and their contribution to developing and training future radiologists should be more widely recognized. Perhaps a trip to the museum would benefit the exhausted radiology resident in many ways: improving well-being and also exercising critical observation skills.

References

- Naghshineh, Sheila, Hafler JP, Miller AR et al. Formal art observation training improves medical students’ visual diagnostic skills.” Journal of General Internal Medicine vol. 23,7 (2008): 991-7.

- Graber ML. The incidence of diagnostic error in medicine. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):ii21-ii27.

- Mukunda N, Moghbeli N, Rizzo A, Niepold S, Bassett B, DeLisser HM. Visual art instruction in medical education: a narrative review. Med Educ Online. 2019; 24(1):1558657.

- Pieter Breugel the Elder. Landscape with the Fall of Icarus. c1555.

- Fildes, Luke. The Doctor. 1891, The Tate Britain, London.

- Donald, J.J. and Barnard, S.A. Common patterns in 558 diagnostic radiology errors. Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Oncology, 2012; 56:173-178.

- Groopman, J., Hartzband, P. Beware of ‘search satisfaction,’ a common cognitive error. Mindful Medicine (2008).

- Braverman, Irwin M. To see or not to see, 344.

- Adrian-Harris D. Aspects of visual perception in radiography. Radiography. 1979; 45(539):237-243.

- Goodman, Thomas R., and Michael Kelleher. Improving novice radiology trainees’ perception using art. Journal of the American College of Radiology 2017;14(10):1337-1340.

- Goodman, “Improving novice radiology trainees’ perception using art”, 1339.

- University of Massachusetts Department of Radiology. Museum Nights: Art observation improves radiology residents visual perceptive and descriptive skills. Accessed September 9, 2020. https://www.umassmed.edu/radiology/special-projects/resident-art-observation/

KRISTIN KRUMENACKER earned a Bachelor of Science in Biology from Georgetown University in 2018. She is currently a third-year medical student at the Renaissance School of Medicine and is concurrently pursuing a Master of Arts in Medical Humanities, Compassionate Care, and Bioethics in conjunction with her MD.

Fall 2020 | Sections | Books & Reviews

Leave a Reply