James L. Franklin

Chicago, Illinois, United States

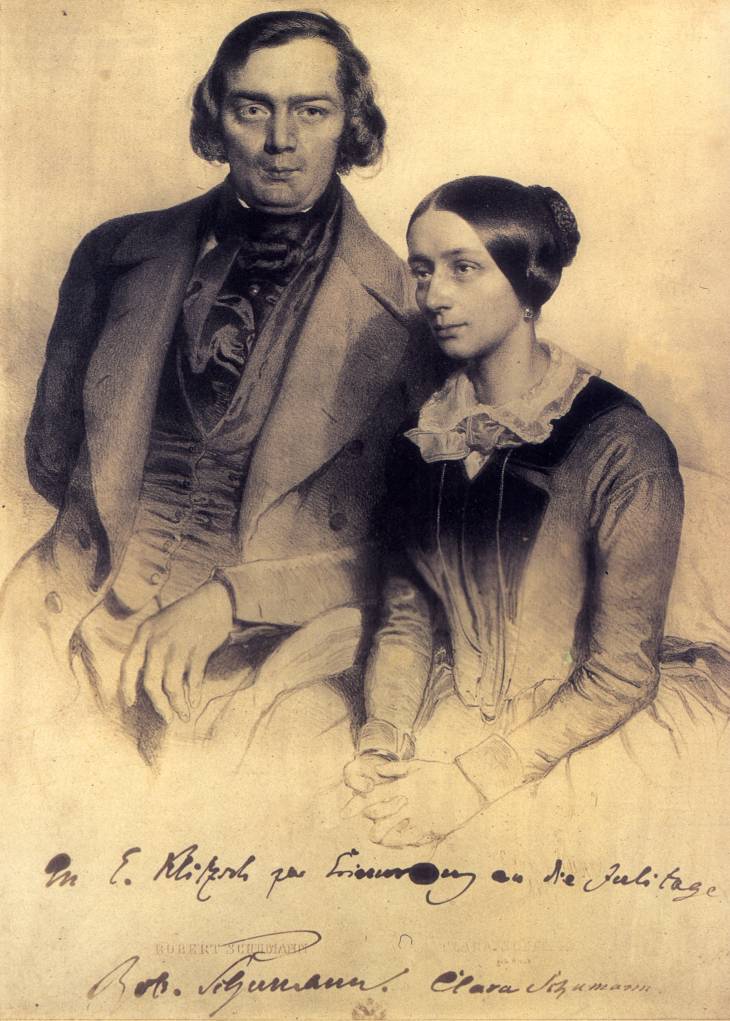

The death of the American pianist Leon Fleisher (1928–2020)1 whose brilliant career as a piano soloist was upended in his mid-thirties by the development of a crippling movement disorder affecting his right hand, brings to mind the composer Robert Schumann whose youthful ambition to become a piano virtuoso was similarly snuffed out by a hand injury. Mr. Fleischer acknowledged later in life that his injury allowed him to pursue a richer life in music than if he had followed the conventional career of a virtuoso pianist. Likewise, Robert Schumann’s hand injury forced him to turn his creative energies to composing for which we are all the richer. As discussed by musicologist and pianist Charles Rosen in his book, The Romantic Generation, Robert Schumann holds a preeminent place among the composers of the middle third of the nineteenth century.2 Schumann’s large and diverse compositional output along with his critical essays on music that appeared in his journal Neue Zeitschrift fűr Musik (New Musical Journal) are his lasting legacy.

Robert Schumann was born on June 8, 1810, in Zwickau, Saxony. He was amazingly productive in spite of intermittent signs of a progressive mental illness that culminated on February 27, 1854, when he attempted to drown himself in the Rhine. Several days later, on March 4, he was transported to a private asylum at Endenich, near Bonn where he died twenty-eight months later on July 28, 1856, at the age of forty-six. The causes of his mental illness and death have received extensive historical investigation. Current opinion supports a bipolar affective disorder first comprehensively examined in a biographical study by psychiatrist Peter Oswald, The Inner Voices of a Musical Genius (1985).3 Prior to that, a diagnosis of neurosyphilis was held to be the cause of his mental deterioration and there is much evidence to support it.4 This diagnosis has been suspected because Schumann reports in his diary on May 12, 1831, after sexual contact with a young woman, Christel, that he was concerned about a wound on his penis which has been considered to have been a syphilitic infection. While in the asylum, his physician, Dr. Franz Richarz, kept a journal about his famous patient. In September 1855, Richarz recorded Schumann’s notation that “In 1831, I was syphilitic and treated with arsenic.”5 Against the diagnosis of neurosyphilis, he married Clara Wieck in 1840 and they had five children. Neither she nor any of their children showed evidence of infection with the disease. A review of his medical records from the Asylum in Endenich suggests that he died from malnutrition.

A second item in Schumann’s medical biography, the subject of this paper, is the hand injury that ended his dream of becoming a piano virtuoso. A clinical picture of this impairment emerges from several sources: Schumann’s personal diary, letters to friends, observations of his teacher Friedrich Wieck, and contemporary accounts by physicians who examined him and recorded their findings.

Schumann first began piano lessons at age seven with Johann Gottfried Kuntsch, a local organist in Zwickau. His general studies were in the Zwickau Lyceum where he remained until the age of eighteen. The school was strong in classical studies and fostered his aptitude for literature as well as music. By fifteen years of age his musical abilities had exceeded those of his teacher. The death of his father, August, at fifty-three years of age in 1826, led his mother to recommend he pursue a legal career despite his preference for music. He enrolled in Leipzig University as a law student in 1828 and it was there that he first met Friedrich Wieck, a highly respected piano teacher whose daughter Clara was a piano prodigy at the age of nine. In 1829 he transferred to the University of Heidelberg to study jurisprudence with Anton Justus Thibaut, an enthusiastic amateur musician who did little to foster his interest in the law. In a letter dated July 30, 1830, he wrote his mother declaring his intention to pursue music and asking her to write Friedrich Wieck asking him to accept her son as a piano student. He returned to Leipzig in the autumn of that year and commenced his studies with Wieck who proclaimed he would make Schumann an outstanding virtuoso of the day.

Publicity photo of Leon Fleisher. Seattle Symphony Orchestra, photographer: Bender. Via Wikimedia

During the first months of his stay in the Wieck home, he practiced the piano 6–7 hours a day. A survey of entries in his diary reveal the daunting regimen he followed. One sample reading:

“2 hours finger exercises – Toccata 10 times – finger exercises 6 times – variations 20 times myself – and still didn’t work with the Alexander Variations in the evening – frustration over this – extreme frustration (January 4, 1830).”

Schumann was also known to have traveled with a silent or “dumb” keyboard which allowed him to practice in circumstances whenever a piano was not available. Such a keyboard might have required excessive force and less than ideal playing posture.

In addition to the manic manner in which Schumann pursued his piano studies, he was also under intense psychological pressure. His mother, who controlled the financial strings to the inheritance he had received from his father’s estate, allowed him to study with Wieck, but had set a six-month trial period of study with Weick after which the teacher would give her an honest appraisal of her son’s prospect as a piano virtuoso.

Schumann’s first reference to difficulties with his hand, numbness in a finger, comes in January 1830. In September, a letter written to his friend, Agnes Carus, states: “it came to such a point that whenever I had to move my fourth finger, my whole body would twist convulsively and after six minutes of finger exercises I felt the most interminable pain in my arm, in short a complete breakdown.”

Schumann came to realize that Wieck was more interested in the training of his daughter Clara who, then eleven years of age, was a far more advanced student. Father and daughter left on a concert tour in Paris from September 1831 until April 1832. Eckart Altenmüller has reviewed multiple entries from Schumann’s diary beginning in the spring of 1831 that reveal the increasing frustration he experienced practicing.6 During this period, he turned to mechanical devices to speed up his progress. He developed an apparatus to improve the strength in his middle finger christening it “Cigar mechanics.” He ordered a commercial device, Johann Logier’s Chiroplast,7 designed to give each finger greater power by briskly pulling to an extreme degree the finger inserted into the mechanism toward the back of the hand.

Wieck strongly objected to the use of such devices though they were sold in his own piano shop. He would later write in a piano method that a “famous student” had used such a machine with disastrous results. By May and June, Schumann recorded in his diary that his third finger “seemed really irreparable” and “completely stiff.”

Inconsistencies as to the specific fingers affected can be found in Schumann’s diaries, correspondence, and the reports of physicians who examined him, for example, reports that were provided when Robert Schumann sought to be released from military service. Dr. Moritz Emil Reuter, a personal friend, provided two reports to the medical board that he had “a complete palsy of the third finger of the right hand and partial of the index finger, which would make him unable to fire a gun.” Doctor Reuter was a good friend of Clara and Robert, a witness to their marriage, and likely concerned that Schumann remained at home with his new spouse and not join the Saxon armed forces. Of Dr. Reuter’s description of Schumann’s impaired hand, Marius Fahrer noted: “It is virtually impossible to write without a steady index and medius [3rd finger]. Yet after 1832, Schumann penned the manuscripts for at least 140 compositions . . . wrote for and edited the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, and penned hundreds of letters.”8

From the spring of 1832 to the summer of 1833, he tried to remedy the situation through a variety of treatments—all expensive and unsuccessful—that included rest, diet, electrotherapy or galvanic stimulation, and Tierbäder, or “animal baths,” immersing his hand into the abdominal cavity of a freshly slaughtered animal until the warmth subsided. Another physician he consulted was a well-known Leipzig homeopath Dr. Franz Hartman, who prescribed a “tiny, tiny bit of powder and a strict diet.”9 There has been some speculation in the literature that this might have been arsenic.

It is at this point his attention turned to composition and by March 1834 he writes to his mother not to be troubled over his impaired finger. “I’m able to compose without it and would hardly be happy as a travelling virtuoso. . . . It doesn’t prevent me from improvising [and] has even renewed my courage to improvise for an audience.” In 1833 Schumann started a flirtation with an attractive 18-year-old girl named Ernestine von Fricken with whom he was able to enjoy playing four-hand piano works. As long as he was relaxed, he was able to play, but he would never go back to playing concerts.

Given that the account of Schumann’s hand injury as a body of clinical evidence has been gathered at a distance of almost 200 years, it is remarkable to survey the precision which authors seek to arrive at a diagnosis. In 1971, Eric Sams10 speculated that a mercurial compound was used to treat Schumann for syphilis, however the evidence that he ever had the disease is tenuous and there is no evidence he received mercurial treatment. Henson and Urlich,11 two eminent neurologists relying on early nineteenth-century clinical information provided by doctors who examined Schumann, suggest the problem may have represented a posterior interosseus neuropathy. Marius Fahrer reviewed the problem of Schumann’s hand from an orthopedic perspective and postulated restricted mobility of tendinous connections of the fourth digit.

The possibility that the impairment of Schumann’s right hand may have been due to focal dystonia was first suggested in 1986 by Lisle Merriman in an article documenting focal movement disorders of the hand in six pianists.12 Since that publication several authors have reviewed Schumann’s medical history and support this diagnosis.13

Since the 1980s there has been a growth in the number of clinics across the country devoted to the medical problems of performing artists. These clinics have gathered data on the types and frequency of hand problems arising in instrumentalists. In a 1983 survey of hand difficulties in one hundred musicians (the majority pianists) seen at the Massachusetts General Hospital, inflammatory disorders of the tendons or joints were present in 45% while disorders of motor control (presumably focal dystonia) occurred in 24%.14 Focal dystonia is a diagnosis that has been made with increasing frequency in pianists, string players, and even woodwind instrumentalists.15 Dystonia is a movement disorder manifested by sustained muscle contractions frequently causing repetitive movements or postures. Focal dystonia in pianists is frequently characterized by involuntary curling of the fourth and fifth digit. It is described as being painless and task specific, it will occur only when playing an instrument and not with other activities such as writing. It is more common in men and associated with prolonged practicing of a difficult repertoire or new pieces and the stress related to preparing for concerts or piano competitions. The current understanding of focal dystonia in pianists is that it is a neurologic disorder related to the digital representation of the fingers in the somatosensory cortex. Pianists with focal dystonia show a fusion of the distance between the representation of the index finger and the little finger when compared to healthy control musicians.16

Given the limitations of pathography, we may never really know the precise clinical diagnosis of Schumann’s hand injury. Perhaps what really is important is how it altered the direction of his career and allowed him to find his true métier as a composer. One only has to think of masterpieces that might never have seen the light of day if he had spent his career as a piano virtuoso. In September 1840, Clara Wieck and Robert Schumann, overcoming formidable legal obstacles, won their court battle against her father and were able to marry. In Clara, Robert had found a devoted wife whose musical talents served him well in introducing his music to the public. In a similar vein, it has frequently been observed that Beethoven’s increasing deafness curtailed his concertizing as a pianist and allowed him the time to bring forth the wealth of music he composed. This brings us full circle to Leon Fleisher and how he reconciled the devastating effect of focal dystonia on his career as a virtuoso. We cannot conjure up Robert Schumann and ask him to explain the difficulties he experienced, examine his hand clinically, or observe him improvising at the keyboard. To put a human face on the impersonal diagnosis of focal dystonia, Leon Fleisher has given us his memoir, My Many Lives: A Memoir of Many Careers in Music.17 It is informative to read his account of the insidious onset of his symptoms in 1965 at a time when the diagnosis was unrecognized and to appreciate the impact on his playing and his career. His struggle to get help from the many specialists he consulted echoes the doctors and odd treatments that were offered Schumann. At age eighty, looking back over his life in music, Fleisher came to understand that his affliction allowed him to find a richer experience in music than he might have had as a concert pianist.

References

- Obituary, New York Times, August 5, 2020: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/02/arts/music/leon-fleisher-dead.html

- Charles Rosen, The Romantic Generation, Harvard University Press, 1995

- Peter Oswald, Schumann: The Inner Voices of a Musical Genius, Northeastern University Press, Boston1985

- Deborah Hayden, Pox: Genius, Madness, and the Mysteries of Syphilis, Basic Books, 2004, Chapter 10 Robert Schumann, 1810-1867, pp. 97-111

- Deborah Hayden, Pox: Genius, Madness and the Mysteries of Syphilis, Basic Books, 2004, p. 100

- Eckart Altenmuller, Robert Schumann’s Focal Dystonia, Neurological Disorders in Famous Artists, Bogousslavsky J, Booer F (eds), From Neurol Neurosci, Basil, Karger, 2005, Vol 19, pp. 179-188

- Beate Perrey, Schumann’s lives and afterlives: an introduction, The Cambridge Companion to Schumann, pp. 3-37, Cambridge University Press, 2007

- M. Fahrer, The Right Hand of Robert Schumann, Ann Hand Surg, 11 (3), 237-240, 1992

- Anton Neumark, Music & Musicians: Hummel, Weber, Mendelssohn, Schuman, Brahms, Bruckner; Notes on their lives, works, and medical histories, Volume 2, Medi-Ed Press, 1995, p. 264

- Eric Sams, Schumann’s hand injury, Musical Times, 1156-1159, 1971

- R.A. Henson, H. Urich, Schumann’s hand Injury, British Medical Journal. 1, 900-903, 1978

- Lisle Merriman et. Al., Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 1:17-19, 1986

- Richard Lederman, Robert Schumann, Seminars in Neurology, 19, Supplement 1, 17-24, 1999, J. Garcia de Yébenes, Did Robert Schumann Have Dystonia, Movement Disorders, 10 (4), 413-417, 1995,

- Fred H. Hochberg et. Al., Journal of the American Medical Association, 249 (14), 1869-1872, 1983

- Jonathan Newmark and Fred H. Hochberg, Isolated painless incoordination in 57 musicians, Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 50: 291-295, 1987, Richard J Lederman, Focal Dystonia in Instrumentalists, Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 132-136, December 1991, Alice G. Brandfonbrener, Musicians with Focal Dystonia, Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 121-127, December 1995

- Ibid, Eckhart Altenmiller, p. 187

- Leon Fleisher and Anne Midgette, My Nine Lives: A Memoir of Many Careers in Music, Doubleday, 2010

, M.D., is a gastroenterologist and Associate Professor Emeritus at Rush University Medical Center. He is also a member of Hektoen International’s Editorial Board and serves as the President of Hektoen’s Society of Medical History & Humanities.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 1 – Winter 2021