Eelco Wijdicks

Rochester, Minnesota, United States

The great humanitarian filmmaker and auteur Ingmar Bergman used physicians in his films much more frequently than his peers. Bergman’s full filmography, including two films (Thirst and Brink of Life) directed by but not written by Bergman, features sixteen physicians in thirteen films. Excluding the family doctor in Fanny and Alexander with no significant dialogue, the remaining fifteen are psychiatrists (6), gynecologists (5), a surgeon (1), a microbiologist (1), a public health physician (1), and a general physician (1) (Table 1). Psychiatrists were frequently featured, predominantly to allow interpretation of insanity (Persona, Face to Face, From the Life of the Marionettes). Gynecologists appeared onscreen because of their close connection with women and Bergman’s interest in the stresses of the maternity ward (Brink of Life). The bedside manners of his physicians varied from business-like to compassionate to seductive—or sadistic, violating any code of conduct. Bergman created physicians who were revered in their profession but detached in their human relationships. Bergman’s commonly used theme of the foibles of professional authority may explain why he was drawn to these characterizations. In the wake of the recent centennial of Ingmar Bergman’s birth, it is interesting to review films he wrote and directed with physicians in leading or supporting roles.

Thirst involves two juxtaposed stories and romantic relationships with troubled women. Viola consults psychiatrist Dr. Rosengren, who wants to control and seduce her. He even states, “I am God’s representative on earth,” after which Viola rebuts, “You know nothing about life and therefore about suffering; all you do is think.” When she refuses his advances, he threatens to commit her to an asylum. To another patient, who later commits suicide, Dr. Rosengren says: “Go on—have a good cry. I will help you build a strong new personality.”

In Persona, actress Elisabet (Liv Ullmann) becomes mute during a performance of Elektra, but physicians find nothing wrong. In a long, significant monologue, the psychiatrist ridicules her: “I think you should play this part until it is played out, until it is no longer interesting. Then you can drop it, just as you eventually drop all your other roles.”

In Face to Face, Dr. Isaksson, the acting chief psychiatrist at an asylum, responds to a psychotic catatonic patient by saying, “You know that I know you are putting on an act.” Her colleague doubts that anything can be done for this patient and cites another psychiatrist, who said “mental illnesses are mankind’s greatest scourge, and the second greatest is the curing of these illnesses.“ Dr. Isaksson’s loneliness causes her to take an overdose of sleeping pills. Her suicide attempt is unsuccessful, but her unconscious state allows Bergman to create vivid dream encounters with her patients and family.

The Serpent’s Egg introduces Dr. Vergerus, a psychiatrist who conducts horrendous psychological experiments (with injections of mind-altering drugs). One involves a man confined in a cell, unable to move limbs, in total darkness and without sound. Other experiments show how long it takes for a woman to become mad from an endlessly crying baby, the effects (suicide) of a mind-altering injection, or the induction of an odorless gas leading to major aggressive responses. Dr. Vergerus uses these psychological experiments to create a new society and to reshape it by “controlling the destructive ones and exterminating the inferior” and explains how he recruits volunteers: “[It was] no trouble, I assure you. People will do anything for a little money.”

From The Lives of the Marionettes impresses as classic Freud. Psychiatrist Jensen is visited by Peter Egermann, who obsessively fantasizes about killing his wife. Unimpressed, Jensen views these recurrent thoughts as a malady of the elite. Peter explains how he would kill his wife, and Jensen tells him that this method would be slow and messy. He offers Peter admission to his clinic. Peter eventually kills a prostitute with the same name as his wife. Admitted to an asylum, he withers away in deep regression and sleeping with his childhood teddy bear. As stated in the film, “dying from mental illness is similar to dying from thirst or hunger.” Most disturbing is the psychiatrist’s denial of any prior concerns with Peter when questioned by the authorities. In order to cover up his dalliance with Peter’s wife, he claims that he found Peter to be mentally sound.

The second most common specialist is the gynecologist. A Lesson in Love is a comedy about the gynecologist Dr. Erneman, his love affair, and his subsequent reunion with his wife. Repeatedly, women ask him if it is not “difficult” for a gynecologist to see attractive women. In an extended opening scene, he is overcome by repressed desire and tries to avoid giving in, but eventually, the flesh wins.

Bergman’s nihilistic depiction of motherhood and delivery in Brink of Life shows the common trope of screams of delivery and obstetric emergencies. The healthiest woman in the ward has an unexplained stillbirth. The three gynecologists are sympathetic. One doctor handles a patient’s miscarriage compassionately by explaining the fetus had no chance and that after a dilation and curettage, the patient will be ready for another pregnancy. Dr. Larsson, who later reveals she is unable to have children, counsels a pregnant teenager ambivalent about abortion that unwed mothers are now much better accepted in Sweden.

A number of other physicians are used. The Magician revolves around the mesmerist Vogler, who does not believe in his powers and is facing humiliation. Public Health Minister Vergerus exposes the trickery. Shame briefly shows a sadistic physician inspecting prisoners and deciding that the one that can stand is physically all right. Another prisoner, apparently asleep on the floor, is actually dead; the physician sardonically asks to move him away “to rot elsewhere.” He corrects a shoulder dislocation without sedation and then, as an apparent excuse for his behavior, tells everyone “we are not well organized.” Dr. Vergerus in The Touch is a surgeon living in a large modern home with a book-lined study. He is too preoccupied with his patients and conferences to notice his wife’s infidelity. Isak Borg of Wild Strawberries, who is invited to return to his alma mater to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of his doctorate, has vivid, troubling dreams in which he foresees his own death and relives his medical examinations. In these dreams, the examiner declares him professionally incompetent and a failed human being. He pleads for lenience on medical grounds (“I have a weak heart”) but receives no mercy. Wild Strawberries is about the challenges of being both a good physician and a considerate father, and the protagonist’s daughter reminds him that he has failed miserably.

Scholars agree that Ingmar Bergman is one of the singular talents in cinema. With Bergman we are often in a world of insanity, unexpected shock, frustration, humiliation, and haunting dreams. Mystifying screenplays are a singular characteristic of his work, and within that world are many physicians. They may be exemplars of his view of the medical profession as well as useful characters who advance the plot. His celluloid physicians are contrasts between two extremes. We encounter mischievous caricatures who do very little actual doctoring. The bedside manners of the physicians in The Serpent’s Egg and Shame are criminally sadistic, violate any possible code of conduct, and tax our disbelief. With the exception of the compassionate gynecologists in Brink of Life, Bergman’s portrayal of physicians generally leaves a bad impression.

How does his depiction of physicians compare with his peers in Europe and the US? Bergman’s comparably prolific peers—in a similar, active, three-decade lifespan—made infrequent use of physicians. Fellini, Ozu, and Bunuel did not use physicians in major roles. Kurosawa used five physicians in the films Drunken Angel (1948), The Quiet Duel (1949), Ikiru (1952), and Red Beard (1965).1 Kurosawa’s realistically portrayed physicians are notable for their dedication (despite lack of resources) and rationality. Their profession has usurped their private lives. Moreover, in Japan the term “Red Beard” even came to denote a physician who is available at all times and unmotivated by financial incentives.1 Hitchcock famously used Ingrid Bergman as a psychiatrist in Spellbound. Huston’s fascination with hypnosis and psychoanalysis led to Freud: The Secret Passion, but he used no other physician in his large body of work.

Filmmakers imaging insanity, haunting nightmares, and existential fears do not need a comprehensive knowledge of medicine, but the genre stills allow their imagination free reign. Despite many interviews and two autobiographies,2,3 we know comparatively little about how Bergman viewed medicine as a whole. Only one film (Brink of Life) identified a medical advisor.

Bergman’s screenplays provide a hint of what he thought about psychiatrists; his depiction of the psychiatrist’s diagnosis of mental illness in Persona, Face to Face, and From the Life of Marionettes wrongly implies that patients fake mental illness and need to step out of their behavior. Moreover, Bergman and many fellow filmmakers, including Litvak, Wiseman, Fuller, and Forman, were interested in whether psychiatric commitment violated patients’ civil liberties.4-7 Face to Face shows Dr. Isaksson reading Prisoners of Psychiatry by attorney Bruce Ennis,8 who questioned the rationale for committing patients to asylum. Similar threats of psychiatrists committing patients as punishment were seen in Thirst and From the Life of Marionettes. In the latter, Bergman specifically wrote the psychiatrist scene with contempt: “the whole analysis is a conscious hoax: a cynical codification of a bloody drama in slippery psychiatric terms.”2 Bergman wanted to convey that the psychiatrist knew what could happen but let it happen because of personal ulterior motives. According to Bergman, “Peter should have shot the doctor.”2

| TABLE 1: Bergman’s Physicians | |

| THIRST (1949) | Hasse Ekman as Dr. Rosengren (Psychiatrist) |

| A LESSON IN LOVE (1954) | Gunnar Björnstrand as Dr. Erneman (Gynecologist) |

| WILD STRAWBERRIES (1957) | Victor Sjöström as Dr. Borg (Microbiologist) |

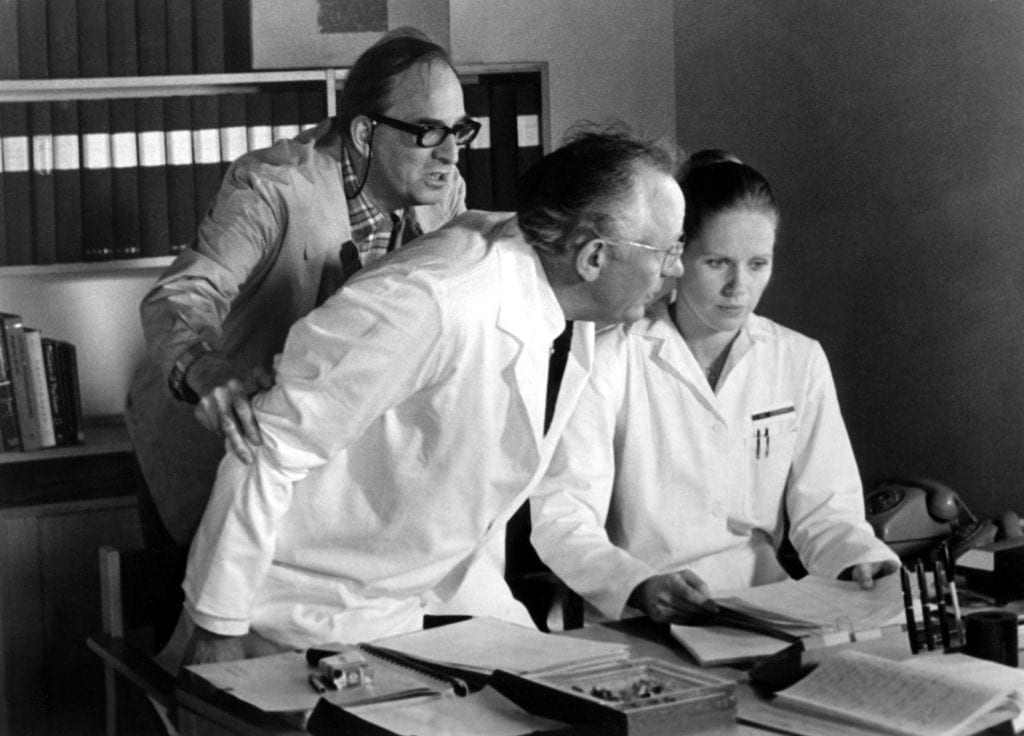

| BRINK OF LIFE (1958) | Margaretha Krook as Dr. Larsson (Gynecologist) Gunnar Sjöberg as Dr. Nordlander (Gynecologist) Gunnar Neilsen as unnamed (Gynecologist) |

| THE MAGICIAN (1958) | Gunnar Björnstrand as Dr. Vergerus (Health Minister) |

| PERSONA (1967) | Margaretha Krook as unnamed (Psychiatrist) |

| SHAME (1968) | Ulf Johansson as unnamed (Doctor) |

| THE TOUCH (1971) | Max von Sydow as Dr. Vergerus (Surgeon) |

| FACE TO FACE (1976) | Liv Ullman as Dr. Isaksson (Psychiatrist) Ulf Johansson as Dr.Wankel (Psychiatrist) Erland Josephson as Dr. Tomas Jacobi (Gynecologist) |

| THE SERPENT’S EGG (1977) | Heinz Bennent as Dr. Vergerus (Psychiatrist) |

| FROM THE LIFE OF THE MARIONETTES (1980) | Martin Benrath as Dr. Jensen (Psychiatrist) |

References

- Flores G. Mad scientists, compassionate healers, and greedy egotists: the portrayal of physicians in the movies. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94(7):635-658.

- Bergman I. Images: My Life in Film. New York: Arcade Publishing; 1994.

- Bergman I. The Magic Lantern: An Autobiography. Viking Adult; 1988.

- Fuller S. Shock Corridor. Allied Artists Pictures. September 11, 1963.

- Litvak A. The Snake Pit. 20th Century Fox. November 4, 1948.

- Wiseman F. Titicut Follies. Zipporah Films, Inc. October 3, 1967.

- Forman M. One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest. United Artists. November 19, 1975.

- Ennis B. Prisoners of Psychiatry: Mental Patients, Psychiatrists and the Law. New York: Avon Books; 1974.

EELCO F. M. WIJDICKS, MD, PhD, is Professor of Neurology at Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester Minnesota, and Associate Professor of the History of Medicine. He has written on film in Neurology, JAMA Neurology, Neurology Today, The Lancet Neurology, and Mayo Clinic Proceedings. His book Neurocinema: When Film Meets Neurology was published in 2015 and Cinema, MD: A History of Medicine on Screen, in 2020.

Leave a Reply