Richard Zhang

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States

Shanghai, 1936: Positioned at the Yangtze Delta, this sprawling, bustling seaport was a multiplicity of cities. It was China’s most lucrative commercial hub for many business elites; a lavish, cosmopolitan adopted home for expatriates from at least forty-eight different nationalities; and a chaotic urban jungle for prostitutes, gangsters, and slum-dwellers in districts like Zhabei.1 The city’s recent, massive economic growth had been accompanied by not only population growth, but also expansion of mass media and pharmaceutical culture.2

These two industries benefited Shanghainese business and political elites who sought an external image of modernity by portraying themselves as healthy and mentally hygienic.3 Media and medicine frequently intersected as advertisements for clinics, mental hospitals, and brain-targeting patent drugs proliferated and contributed to a more modern image of China.4-7 Western-appearing medical technologies were integral to China’s geopolitical strengthening; many Chinese agreed with former president Li Yuanhong that “Nothing has done so much to modernize China as modern medicine.”8,9

The popularity of Western-style medicine in the time before the Japanese invasion was inextricably tied to the expansion of mass media. Two newspaper advertisements for popular tonics illuminate how Shanghainese elites of the 1930s selectively consumed patent psychopharmaceuticals to contribute to an international image of a medically modern China, and thus liberation from foreign framings of Chinese as backwards.

I. “Ailuo Brain Tonic,” Tie Bao, March 9, 1936.

Throughout March 1936, this advertisement was published in the Shanghainese newspaper Tie Bao, connecting the tonic to a popular diagnosis, neurasthenia (神經衰弱), that was associated with deficiencies in sleep, energy, and mood.10-12 At the bottom, the advertisement listed the drug’s vendor as “The Shanghai Sino-French Drugstore.”

Owned and marketed by entrepreneur Huang Chujiu, who had trained in Chinese medicine but lacked biomedical training, this product was created from Chinese medicine ingredients formulated by pharmacist Wu Kunrong.13 Huang explained his product in terms of Chinese medical theory relatable to his customers, through classical notions of yin and yang orbs, and claimed to have discovered an efficacious synthesis in the tonic between such orbs and Western medical theory. He advertised the tonic under the Western-sounding pseudonym of Dr. T.C. Yale and gave his business the cosmopolitan-sounding name of “Sino-French Drugstore,” which was possible because of its headquarters in the Shanghai French Concession. Though not biomedical in formulation, the hybridized Ailuo Brain Tonic carried connotations of Western medical modernity that appealed to many Republican Chinese.

By proclaiming the tonic as efficacious for neurasthenia, the Tie Bao advertisement tied the drug to a Western-originated psychiatric diagnosis. Neurasthenia had been popularized in the West in 1869 by American neurologist George Beard, and its symptoms included “dyspepsia, headaches, paralysis, insomnia,” and “mental depression, with general timidity.”14,15 It had been tied to the upper classes, who were seen as prone to “nervous exhaustion” given the psychic demands of capitalism placed on them.16 Later regarded by biomedicine as diagnostically vague, neurasthenia had died out as a classification in the West by the 1920s, where expanding inquiry into endocrinology and psychotherapy offered new powerful explanations and remedies for such symptoms.17

Yet since the 1910s, neurasthenia had taken on new significance in China as a disease of upper-class modernity. Chinese elites during the 1930s associated neurasthenia with many of the same symptoms that the diagnosis had been associated with in the West.18 These elites believed that neurasthenia was a condition unique to intellectuals, businessmen, and others like themselves who worked with their minds instead of their hands.19 Chinese elites who accepted a new identity as neurasthenic often reconstituted themselves as buyers of modern pharmaceutical commodities, including brands such as Dr. Jiang Shaosong’s Pills and Esfar.20,21

Neurasthenia gained widespread acceptance largely because its notions of nervous exhaustion aligned with common notions of depletion in Chinese medicine.22 Chinese medicine had long explained illnesses as related to imbalances or disruptions in bodily circulation of the vital energy-force qi (氣). In turn, neurasthenia became re-interpreted by many Chinese as resulting from pathologic bodily qi depletion. Health-related columns in newspapers mentioned “neurasthenic qi deficiency,” and both Chinese medicine practitioners relying on qi-based explanations and biomedical practitioners treated neurasthenia during this period.23-26 By imbibing the tonic, elites could consume a modern-appearing patent drug framed in Chinese terms, produced for a disease of civilization and modernity that was also framed in Chinese terms. The intersection of the tonic with neurasthenia in the Tie Bao advertisement illuminates how Republican elites valued an outward image of Western medical modernity, but had substantial agency in selectively incorporating framings of disease from the West.

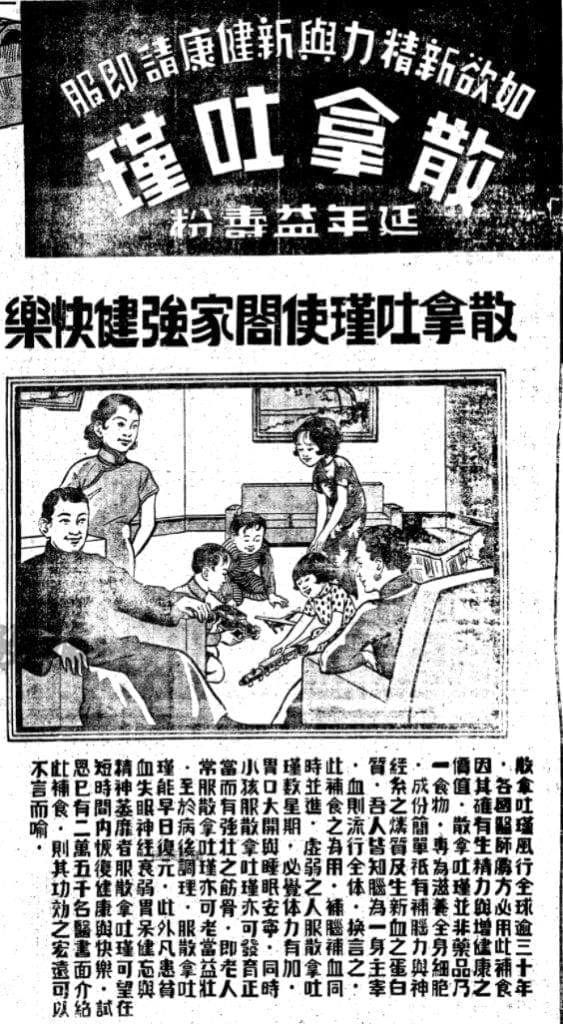

II. “For Greater Energy and Health, Take Sanatogen Now,” Shen Bao, October 25, 1936.

This advertisement was a shrewd adaptation of a foreign pharmaceutical to Chinese interests.27 It provides a small window into how Chinese elites envisioned a culturally hybridized modernity in the household. The advertisement translated Sanatogen into sanna tujin (散拿吐瑾), preserving the name’s Western sound for consumers interested in Western pharmaceuticals. The image portrayed cheerful parents wearing Chinese-style clothes—and the mother donning a fashionable qipao dress—while happy children played with toy models of Western-originated technologies: an automobile, an airplane, and a train. The drug itself was advertised as owned and produced by a Chinese branch of a German pharmaceutical company.28,29

Lavishly praising its product’s efficacy for both mind and body, the advertisement touted that Sanatogen, “popular all over the world for thirty years,” could improve an entire family’s strength and happiness. It noted that the medicine contained a phosphate-containing compound that was neuroprotective, as well as proteins that could boost blood cell production. This combination purportedly made it effective for helping consumers recover faster from neurasthenia, anemia, and symptoms of poor appetite, fatigue, and amnesia. The advertisement claimed that over 25,000 physicians worldwide had endorsed Sanatogen.

More so than the Ailuo campaign, this advertisement reconciled traditional family values with medical modernity. Depicting happy, well-dressed parents and children, and expounding on the drug’s benefits for the happiness of an entire family, it promised that the German-made drug could help preserve the core unit of traditional Chinese society, showing that that medical modernity and social conservatism were not mutually exclusive.30

Both drugs appealed to elite Chinese tastes for outwardly Western products. However, in contrast with the Ailuo Brain Tonic’s advertisements that promoted benefits in classical Chinese terms, Sanatogen avoided references to yin and yang orbs. Whereas the Ailuo Brain Tonic attempted to reconcile Western medicine with traditional aspects of Chinese medicine such as qi, Sanatogen was biomedical in its formulation and explanation. Thus, even though many Chinese elites outwardly valued Western health products as modern, a society-wide plurality of ways of conceptualizing medicine remained.31,32

III. Psychopharmaceutical modernity

Modernization in Shanghai was a creative, selective, and locally contingent process. The Ailuo Brain Tonic was a mass-produced patent drug that could be explained through yin and yang. Sanatogen was German-originated, but could still appeal to Chinese values. The making of Republican Chinese psychopharmaceutical modernity, though outwardly Western in its products, required the complex intersection of elite Chinese interests and capital, both Chinese and Western medical epistemologies, and clever cross-cultural adaptations.

This process in Shanghai is a powerful example of what scholars Warwick Anderson, Edward Said, and Dipesh Chakrabarty discuss when they challenge the assumption of an objective and universally applicable knowledge emanating from a Western center to a non-Western periphery.33-35 Their scholarship helps to highlight and recognize indigenous agency and complexity involved in adoptions of Western technoscience. By approaching “modernity” in non-Western localities such as Shanghai through local media records and perspectives, historians of medicine can resist Euro-American narratives that essentialize and claim authority over non-Western experiences.

Image citation

- Beijing Airusheng shuzihua jishu yanjiu zhongxin 北京爱如生数字化技术研究中心. Shenbao shujuku 申報數據庫 [Shen Bao Database]. Beijing: Beijing Airusheng shuzihua jishu yanjiu zhongxin, 2011.

References

- Harmsen, Peter. Shanghai 1937: Stalingrad on the Yangtze. Vol. 1. (Havertown, PA: Casemate Publishers & Book Distributors, 2015), 17.

- Chin, Sei Jeong. “Print Capitalism, War, and the Remaking of the Mass Media in 1930s China.” Modern China 40, no. 4 (August 8, 2013): 393–425.

- Rogaski, Ruth. “Weisheng and the Desire for Modernity.” In Hygienic Modernity: Meanings of Health and Disease in Treaty-Port China, 1:225–53. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2004.

- “Shanghai puci liaoyangyuan zhuanzhi jingshen shenjingbing kaizhen qishi”上海普濨療養院專治精神神經病開診啟事 [Opening of the Puci Sanatorium for Nervous Diseases]. Shen Bao 申報. September 20, 1935.

- Cochran, Sherman. “Marketing Medicine and Advertising Dreams in China, 1900-1950.” In Becoming Chinese: Passages to Modernity and Beyond, 1st ed., 62–92. University of California Press, 2000.

- “Liangjunqing yixue boshi zhensuo” 梁俊青醫學博士診所 [Dr. Liang Junqing’s Clinic]. Shen Bao 申報. January 1, 1934.

- “Zhushaoyun yisheng zhensuo” 朱少雲醫生診所 [Dr. Zhu Shaoyun’s Clinic]. Shen Bao 申報. January 7, 1937.

- Lei, Sean Hsiang-Lin. “Sovereignty and the Microscope: The Containment of the Manchurian Plague, 1910-1911.” In Neither Donkey nor Horse: Medicine in the Struggle over China’s Modernity, 1st ed., 1:21–44. The University of Chicago Press, 2014.

- Baum, Emily. “The Psychiatric Entrepreneur, 1920s–1930s.” In The Invention of Madness: State, Society, and the Insane in Modern China, 86–110. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018.

- “Ailuo bunaozhi” 艾羅補腦汁 [Ailuo Brain Tonic]. Tie Bao 鐵報. March 9, 1936.

- “Ailuo bunaozhi gongyonglu” 艾羅補腦汁功用錄 [Ailuo Brain Tonic’s Function Record]. Xinwen Bao 新聞報. October 30, 1904.

- “Ailuo bunaozhi qingkan zhenzheng shiyan zhi baozhengshu” 艾羅補脑汁請看真正實驗之保證書 [Ailuo Brain Tonic, Please See the Guarantee of the Real Experiment]. Shi Bao 時報. November 10, 1904.

- Cochran. “Marketing Medicine and Advertising Dreams in China, 1900-1950.” 62—92.

- Beard, George. “Neurasthenia, or Nervous Exhaustion.” The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 80 (April 29, 1869): 217–21.

- Beard, George. “Other Symptoms of Neurasthenia (Nervous Exhaustion).” The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 6, no. 2 (April 1879): 246–261.

- Beard. “Neurasthenia, or Nervous Exhaustion.” 217-21.

- Schuster, David. “The Decline of Neurasthenia.” In Neurasthenic Nation: America’s Search for Health, Happiness, and Comfort, 1869-1920, 140–58. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2011.

- Shapiro, Hugh. (2000, June). Neurasthenia and the assimilation of nerves into China. Paper presented at the Symposium on the History of Disease, Academia Sinica, Institute of History and Philology, Nankang, Taiwan.

- Baum, Emily. “The Psychiatric Entrepreneur, 1920s–1930s.” In The Invention of Madness: State, Society, and the Insane in Modern China, 86–110. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018.

- Baokang Medicine 保康藥. “Jiangshaosong yishi chufang jianzhi yijing wan” 蔣紹宋醫師處方監製遺精丸 [Dr. Jiang Shaoshong Prescribes and Produces Spermatorrhea Pills]. Xinwen Bao 新聞報. June 10, 1931.

- “Aisifa” 爱斯法 [Esfar]. Xinwen Bao 新聞報. October 30, 1933.

- Monnais, Laurence. “Colonised and Neurasthenic: From the Appropriation of a Word to the Reality of a Malaise de Civilisation in Urban French Vietnam.” Health and History 14, no. 1 (2012): 121–42.

- “Shenxu shenruo” 腎虛身弱 [Kidney Deficiency and Weakness]. Shen Bao 申報. November 19, 1915.

- “Tianxia chiming diyi lingyao wei yulin minggui shiyan” 天下馳名第一靈藥維育麟名貴實騐 [The World’s Well-Known, Number One Elixir Yulin’s Famous Experiment]. Shen Bao 申報. June 13, 1933.

- “Shou’er Kang” 壽爾康 [Shou’er Kang]. Shen Bao 申報. December 8, 1933.

- Wang, Wen-Ji. “Neurasthenia and the Rise of Psy Disciplines in Republican China.” East Asian Science, Technology and Society 10, no. 2 (2016): 141–60.

- “Ruyu xinjingli yu xinjiankang qing jifu sanna tujin” 如欲新精力與新健康請即服散拿吐瑾 [For Greater Energy and Health, Take Sanatogen Now]. Shen Bao 申報. October 25, 1936.

- Ibid.

- Lin, Pei-yin, and Weipin Tsai. Print, Profit, and Perception: Ideas, Information and Knowledge in Chinese Societies, 1895-1949. Vol. 1. Leiden: Brill, 2014.

- Dirlik, Arif. “The Ideological Foundations of the New Life Movement: A Study in Counterrevolution.” The Journal of Asian Studies 34, no. 4 (1975): 945–80.

- Lei, Sean Hsiang-Lin. Neither Donkey nor Horse: Medicine in the Struggle Over China’s Modernity. Vol. 1. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2014.

- Leung, Angela Ki Che, and Izumi Nakayama. Gender, Health, and History in Modern East Asia. Vol. 1. (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2017), 172.

- Anderson, Warwick. “Introduction: Postcolonial Technoscience.” Social Studies of Science 32, no. 5/6 (December 2002): 643–58.

- Dirlik, Arif. “Chinese History and the Question of Orientalism.” History and Theory 35, no. 4 (December 1996): 96–118. https://doi.org/10.2307/2505446.

- Chakrabarty, Dipesh. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. Vol. 1. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000.

RICHARD ZHANG is an MD/MA student completing his medical studies at Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University, and his MA in History of Science and Medicine at Yale University.