M.K.K. Hague-Yearl

Montréal, Québec, Canada

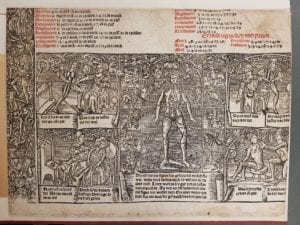

Sitting with little fanfare inside a twentieth-century red hardcover binding is a single leaf whose bibliographic record contains brackets of uncertainty: “[Calendar for Austria, 1496.] [Kaspar Hochfeder, Nürnberg? 1495.]” The catalogue offers only a basic description: “The woodcut occupying the whole lower portion depicts a zodiac man, two bloodletting scenes, a sickbed, and scarification. The left border represents a tree of Jesse.”1 Immediately, one might argue with the accuracy of the description: surely it would be more appropriate to mention three bloodletting scenes, two of which depict venesection and one scarification. Regardless, the details that have been left out are both interesting and significant. Namely, the two venesection scenes depict women even though the German captions contain no information to link the contents of the calendar to either sex. Rather, the rhyming couplets that accompany the three bloodletting images open with a general acknowledgement that there are many veins from which to choose when bleeding; the implication is that following the calendar will lead to a good result.2

The question at the heart of this piece is why the venesection scenes depict women and whether women figured more prominently in the history of bloodletting than may previously have been recognized. While this study will consider evidence that exists for bloodletting of and by women, it opens with an acknowledgement that there are important and relevant questions for which answers do not currently exist. For instance, does the answer to “why women” lie in the provenance of the document; might it have been made with a female audience in mind? What will become clear in this overview is that women were anything but remarkable in the history of bloodletting, but that this very lack of remarkability is worthy of exploration.

Women in the Middle Ages were regular subjects of bloodletting, despite a medical literature that may be interpreted as having contraindicated the practice for those who menstruated. In the ancient theories that dominated learned medicine, women were regarded as being naturally cold; menstruation was the female body’s mechanism for getting rid of excesses from food which the warmer male body could burn off.3 It might stand to reason that menstruating women were rarely bled because their bodies expelled impurities on a monthly basis, but the reality was more complicated. Regardless of sex, bloodletting was recommended with circumspection.4 The presumption of a medical narrative that distinguished between male and female is further undermined by the observation that medieval religious women underwent periodic bloodletting according to the same rules as men.

Periodic bloodletting was the practice of regular prophylactic bleeding that was a legislated part of medieval monastic life. Nearly every monastic customary included a chapter on bloodletting: how to ask permission to be bled; the times when it was permitted or prohibited (mainly to avoid disruption to the work of God); the nature of food and drink to be consumed during the three-day convalescence that followed venesection. By the time of the First Aachen Synod of 816, periodic bloodletting was a regular enough part of monastic life to be included in the earliest written customs.5 Over the centuries, stricter rules for bloodletting were built into reformed regulations addressing the religious routine; the focus was not on the medical aspects of bloodletting, but on ensuring that the relaxation of rules that coincided with the three-day recovery did not lead to a lowering of disciplinary standards.6

An analogous transfer of legislation took place as women’s religious houses were formed. Since they took their rules and guidance from the male religious, it should be no surprise that bloodletting was adopted as part of the customs that directed how the religious were to apply the Rule to their daily routine. The casual references to bloodletting in a female context can be found quite early. For instance, in a letter written in the twelfth century, the nuns of Admont (a monastery in the archdiocese of Salzburg that followed the Hirsau reform) offered a male patron two bloodletting tourniquets.7 The casual mention of the tourniquets is evidence of how embedded bloodletting was in cloistered life, whether for men or women. Other evidence of bloodletting’s accepted presence amongst cloistered females comes from the dramatic account Robin Hood’s death. As the story went he visited his cousin, the Prioress of Kirklees, who was well-regarded for her skill as a bloodletter. She betrayed him and bled him to death rather than providing the cure he sought.8 While this story is unique for the crime attached to it, it does reinforce the argument that women not only were bled, but may have played an active role in the practice of bloodletting within their communities.

Incidental evidence points to a lively exchange between monasteries and the societal elite. There are suggestions that those outside of the cloister may have adopted bleeding practices similar to those practised in the monasteries; some may even have been bled at the granges where religious went for their bloodletting and associated convalescence. In a letter from the first half of the thirteenth-century, the Earl of Gloucester wrote to his servant requesting that “two barrels of white wine and two flasks of chestnut wine and one tun of filtered ale” be sent because, “You shall know that I and my countess are having our blood let at N. Therefore see to it that you do not move us to anger by your negligence.”9 As in the cloisters, where bloodletting was followed by a time of rest and reflection, this letter implies that those who had been bled could expect comfort and freedom from worry, lest their recovery be undermined. The communication by the Earl of Gloucester is just enough to suggest that bloodletting as experienced in religious communities was familiar to literate society. While diaries and letters of the lay elite may reveal more information about female bloodletting, to date the best sources remain those from the religious orders, whether monastic customaries or statutes from other religious institutions.

In the hospitals, for instance, male and female religious tended to the infirm poor. In two sets of hospital statutes—those for the Hôtel-Dieu de Paris (circa 1220) and for the Hôpital Comtesse de Lille (circa 1250)—regulations directed at brethren and sisters were presented together. Their respective chapters on bloodletting were no exception: at the Hôtel-Dieu, they were to be bled six times per year.10 Meanwhile, the chapter on bloodletting in the statutes for the female house of Hôtel-Dieu de Vernon reads no differently than would a chapter on bloodletting from a male monastery, specifying bleeding six times a year, and that minuti11 enjoy three days of repose and peace.12 The mid-thirteenth century constitutions for the Dominican sisters of Montargis similarly reflect comparable male models.13 The same was true of a group of Catalan Clares in the fourteenth-century; in this case, bloodletting was to be done four times per year, which agreed with the more ascetic male monastic orders.14 Tellingly, the Gilbertine regulations made their distinction at a hierarchical rather than gendered level: monks and canons could be bled four times, while for brethren and sisters bleeding was limited to three occasions in a year, unless necessity demanded more.15

While the bloodletting of lay women would have been primarily for reasons of physical health, the spiritual metaphor of Christ’s bloodletting was an important element in the monastic experience. One of the most evocative references to bloodletting in guidance written for female religious comes from the Ancrene Riwle.16 Where it lacks in explicit instructions for periodic bloodletting, it excels in establishing a powerful metaphor. In this context, the author presented an analogy of Christ’s bleeding as revulsive: that is, blood was drawn from a place in the body distant to the ailment. The author explained:

in all the fevered world there was not found any healthy part, among all mankind, which might be let blood, except only the body of God, which was let blood on the cross, and not merely in the arm, but in five places, in order to heal mankind of the disease to which the five senses had given rise. Thus the living, healthy part drew out the bad blood from that which was diseased, and so healed that which was sick.16

There were physical differences between men and women that explained why they received separate treatments in medical terms, but periodic bloodletting could further be associated with the blood of Christ. Christ’s blood was not about sexuality; it signified suffering: “blood is redemptive because Christ’s pain gives a salvific significance to what we all share with him; and what we share is not a penis. It is not even sexuality. It is the fact that we can be hurt. We suffer.”18 In this setting, periodic bloodletting itself was not gendered, as it preserved physical health while also serving to realize the spiritual direction to “give blood and receive the Spirit.”19

Returning to the woodcuts that introduced this exploration of bloody women, it should now be clear that there was little remarkable about female bloodletting. Nonetheless, the presence of female characters absent from any acknowledged focus on female physiology is curious. The possibility remains that the calendar was created for a female audience. Though less likely, it may also have been part of a larger work that did address ailments for which women were bled. One final thought relates to the commercial element of printing. Perhaps by including female images, the printer hoped to increase sales. Women sell.

References

- [Calendar for Austria, 1496], [Nuremberg, 1495]. Bibliotheca Osleriana (henceforth B.O.) 7424A, Osler Library of the History of Medicine, McGill University. https://mcgill.on.worldcat.org/oclc/428035767.

- [Calendar for Austria], B.O. 7424A.

- Bettina Bildhauer, “Medieval European Conceptions of Blood: Truth and Human Integrity,” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (2013): S57-76, www.jstor.org/stable/42001729.

- Jacques Jouanna, Hippocrates, trans. M.B. DeBevoise (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1999), 159-160. See also Helen King, “Green Sickness: Hippocrates, Galen and the Origins of the ‘Disease of Virgins’,” International Journal of the Classical Tradition 2, no. 3 (1996): 372-87, www.jstor.org/stable/30222221.

- Mary K. K. Yearl, “Bloodletting as Recreation in the Monasteries of Medieval Europe,” in Between Text and Patient: The Medical Enterprise in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, ed. Florence Eliza Glaze and Brian Nance (Florence: Sismel, 2011), 217-219.

- Yearl, 241-243.

- “Mittimus uobis duo ligamina ad diminutionem sanguinis apta.” Alison I. Beach, “Voices from a Distant Land: Fragments of a Twelfth-Century Nuns’ Letter Collection, Speculum 77 (2002): 44-45, 52.

- The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, ed. F.J. Child, vol. 3 (New York: Folklore Press, 1957), 104-105.

- Martha Carlin and David Crouch, Lost Letters of Medieval Life (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), 73.

- Léon le Grand, Statuts d’hotels-dieu et de léprosaries, receuil de textes du XIIe au XIVe siècle (Paris: Alphonse Picard et Fils, 1901), 51, 73.

- Minuti were those who had been bled.

- Le Grand, 171.

- Raymond Creytens, “Les constitutions primitives des soeurs dominicaines de Montargis (1250),” Archivum Fratrum Praedicatorum 17 (1947): 71-72. For comparison: Cambridge University Library Manuscripts Room, MS LL.2.9, “Constitutiones fratrum praedicatorum,” fol. 72v. See also the fifteenth-century customs for the canons of Windesheim in the Netherlands to the sixteenth-century ones for the female institution “Statuta Windeshemensis, introducta saeculo XV,” in Vetus disciplina canonicorum regularium et saecularium, ed. Eusebio Amort, vol. 1 (Venice, 1747), 591-592 ; “De minutione,” in R.T.M. van Dijk, De Constituties der Windesheimse Vrouwenkloosters vóór 1559 (published Ph.D. Thesis, Katholieke Universiteit, Nijmegen, 1986), part 2, cap. 3.23; Wybren Scheepsma, Medieval Religious Women in the Low Countries, trans. David F. Johnson (Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK: Boydell Press, 2004), 9-10.

- Margarida González i Betlinski and Anna Rubió i Rodón, “La Regla de l’Ordre de Santa Clara de 1263. Un cas concret de la seva aplicació: el monestir de Pedralbes de Barcelona,” Acta Historica et Archaeologica Medievalia 3 (1982), 35.

- L. Holstenius and M. Brockie, eds., “Regulae ordinis sempringensis sive GilbertinorumCanonicorum,” In Codex regularium monasticarum et canonicorum, vol. 2 (Augsberg, 1759), 499.

- The Ancrene Riwle, trans. M.B. Salu (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1956), 188.

- The Ancrene Riwle, 50.

- Caroline Walker Bynum, Fragmentation and Redemption. Essays on Gender and the Human Body in Medieval Religion (New York: Zone Books, 1992), 92.

- Apophthegmata Patrum, Longinus 5, PG 65, cols. 257-258; The Sayings of the Desert Fathers: The Alphabetical Collection, trans. Benedicta Ward (London: Mobray, 1975).

Image Reference

- [Calendar for Austria, 1496], [Nuremberg, 1495]. Bibliotheca Osleriana 7424A, Osler Library of the History of Medicine, McGill University. https://mcgill.on.worldcat.org/oclc/428035767

M.K.K. HAGUE-YEARL, MLIS, PhD, is the Osler Librarian at the Osler Library of the History of Medicine and an Associate Member of McGill’s Department of Social Studies of Medicine. She studied the history of medicine at Yale (Ph.D.) and Cambridge (M.Phil) before turning to archives and special collections librarianship. Her research interests lie in the interplay between medicine and religion in the pre-modern period, and in the transformation of concepts from humoral medicine into scientific paradigms in the modern period.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest

Leave a Reply