JMS Pearce

Hull, England, United Kingdom

|

| Fig 1. Wilder Penfield, Stamp |

Wilder Penfield was not only a great surgeon and a great scientist, he was an even greater human being.

-Sir George Pickering, Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford University

Wilder Penfield (1891-1976) (Fig. 1) was the most gifted pioneer of Canadian neurosurgery. He devised effective surgery for controlling intractable epilepsy and he defined more accurately discrete areas of brain functions. He was the moving force in the founding of the Montreal Neurological Institute.

Born in Spokane, Washington, he spent much of his youth in Hudson, Wisconsin. When he was thirteen his mother learned of the newly established Rhodes scholarship. “This is just the thing for you,” she confidently predicted. With the appropriate modest reserve of youth he confronted the required challenge to become both scholar and athlete.

Penfield went to Princeton University, where he decided to pursue medicine, following the path of his grandfather and father; he later remarked it seemed the most direct way to “make the world a better place in which to live.” His application for the Rhodes scholarship failed so he saved money for his medical education by coaching the Princeton football team. During this time he reapplied and was awarded a Rhodes scholarship for the next year.

Thus he started medicine at Merton College, Oxford in 1914.1 There he was inspired by two of the greatest physicians of the era: Sir William Osler (1849-1919), Canadian-born Regius Professor of Physic, and the Nobel laureate Sir Charles Sherrington (1857-1952), the renowned neurophysiologist. Studies were interrupted by World War 1, when a German torpedo blew up the ship SS Sussex, which was taking him to serve in a French Red Cross hospital, causing serious leg injury; he convalesced at Osler’s home in 1916. A year later he married Helen Kermott with whom he had four children.

|

|

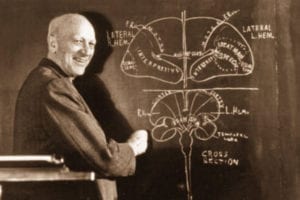

Fig 2. Penfield, brain mapping |

After two years at Oxford, he studied at the Johns Hopkins Medical School to complete his MD in 1918. The following year he was apprenticed to Harvey Cushing (1869-1939), the foremost neurosurgeon in America. He returned to Oxford to complete the final year of his Rhodes scholarship as a graduate student in neurophysiology under Sherrington. He was then appointed Beit Memorial Fellow at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, studying with Percy Sargent, Gordon Holmes, and Kinnier Wilson. After this high-powered clinical and academic apprenticeship with the finest brains in England and America, he obtained in 1921 the Associate Professorship in Surgery at Columbia University, where he developed his surgical techniques with Allen O. Whipple, and established with WV Cone a neurocytology laboratory. Cone came with him to the MNI.

During his postgraduate years in Oxford and London, Penfield had been increasingly occupied by experimental neurophysiology and developed the novel idea of a neurological/neurosurgical center for collaborative research. He therefore joined the medical faculty of McGill University in 1928 and became neurosurgeon at the Royal Victoria and Montreal General Hospitals. With a Rockefeller Foundation grant that yielded $1,232,000 he instigated the opening of the Neuro (Montreal Neurological Institute or MNI) in 1934.2

|

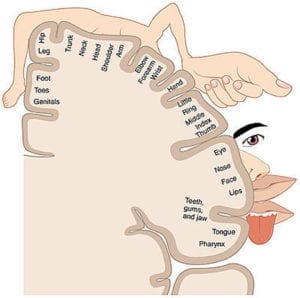

| Fig 3. Penfield’s homunculus |

A few months after his arrival in Montreal, he was called upon to remove a right frontal glioma from his sister Ruth—a terrible experience for them both. But after a two year remission symptoms returned and she died. This terrible event strengthened his passion for advancing neurosurgery.

At the MNI he gradually built a talented team that included Cone, Rasmussen, and Jasper that furthered the techniques of brain surgery and neurological research.3 In some of his epileptics Penfield discovered cortical scars, which he called the meningocerebral cicatrix. He hoped to cure the patient’s epilepsy by removing them. He thought that if he could reproduce a conscious patient’s epileptic aura by applying an electric current to the cortex, he could locate its source, which then he could excise. He achieved this aided by his colleague Herbert Jasper’s (1906-1999) electrophysiology—the “Montreal Procedure”—that allowed patients to remain conscious and describe their reactions while the surgeon stimulated different areas of the brain.4

But a scar or tumor was not always demonstrable. And when no lesion was visible there were few good results. However, he went on to show that in some such cases a second operation did show a scar in the deeper mesial temporal lobe, which included the hippocampus and amygdala. The removal of this lesion, mesial temporal sclerosis, often gave relief from seizures. Not only was this a step forward in the treatment of epilepsy but it yielded important new data on brain physiology and clinical anatomy by his observing the clinical consequences of cortical stimulation.5 By numerous clinical experiments Penfield and his colleagues reported which functions correlated with each stimulus, thereby creating a map (Fig 2) of motor, sensory, and cognitive functions, including an “engram” for memory. The map was demonstrated as a human figure with disproportionately large hands, thumbs, and mouth, which indicated the epileptogenic potential of large cortical areas relative to the whole body. It was famously called the Penfield’s homunculus. (Fig. 3)

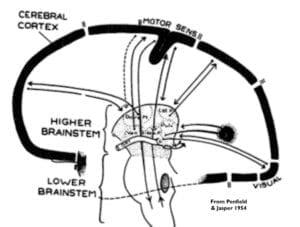

A major new concept was his “centrencephalic center,” which was that central system within the brainstem responsible for the integration and function of the two hemispheres. (Fig. 4) It was involved primarily in epilepsy characterized by initial loss of consciousness, as in petit mal or grand mal attacks (now known as primary generalized seizures) without evidence of a cortical focus.3

|

|

Fig 4. The centrencephalic center. |

Penfield retired from the McGill medical faculty in 1954, and gave up his directorship of the MNI six years later. Amongst many honors, he was president of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada and of the American Neurological Association; he was elected FRS in 1943 and received honorary degrees from Princeton, Oxford, McGill, and Montreal, and received the elite British Order of Merit,

William Feindel, his successor from 1972-1984, said his contributions were recognized as unique by his neurosurgical and scientific colleagues. ED Adrian, another Nobel laureate, described Penfield as:

“a skilled neurosurgeon, a distinguished scientist, and a clear and engaging writer” with qualities of leadership that attracted “devoted colleagues,” but that “his first concern” was always the patient who needed “his surgical skill.”

After he retired he traveled widely and gave many invited lectures. He took a second career as an author, covering more discursive, conceptual matters.6 In 1960, he published a historical novel about Hippocrates The Torch; and in 1967 The Difficult Art of Giving,7 a biography of Alan Gregg, director of the Rockefeller Foundation that had made possible the MNI. In 1975, The Mystery of the Mind8 was dedicated to Sherrington—an account for laymen of his long history of neurosurgical investigations of the brain.

Penfield’s surgical technique stemmed from Harvey Cushing’s surgical ritual following the painstaking operative methods of Halsted. His eclectic operative approach also owed much to Dandy, Horsley, Sargent, Frazier, Whipple, Leriche, and Foerster, which he revealed in his memoirs. His intellectual concepts of neurological function and disorders were strongly influenced by Sherrington, Holmes, Cajal, and Hortega.

Wilder Penfield was a colossus of neurosurgery, a man with extraordinary drive, independence, and tenacity. His life’s work is epitomized by the phrase he chose for a plaque outside the door of the MNI:

Dedicated to relief of sickness and pain and to the study of neurology.

Three weeks before his death he completed the draft of his autobiography, No Man Alone, published in 1977.9 His final work was dedicated “with affection and gratitude” to the memory of his mother. He died aged eighty-five of abdominal cancer on April 5, 1976. His ashes were buried on the family’s farm on Lake Memphremagog. His wife Helen died a year later, her ashes were buried beside his.

References

- Wilder Graves Penfield. https://www.mcgill.ca/neuro/about/history/notable-figures/wilder-graves-penfield

- Feindel W, Leblanc R. ‘The Wounded Brain Healed – The Golden Age of the Montreal Neurological Institute, 1934-1984″ McGill-Queen’s University Press. 2016.

- Penfield W, Jasper H. Epilepsy and the Functional Anatomy of the Human Brain, Boston, Little, 1954

- Loring D W. History of Neuropsychology Through Epilepsy Eyes. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology 2010; 25(4): 259-273.

- Penfield W. The Excitable Cortex in Conscious Man, Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 1958

- Penfield W. The Second Career. Little, Brown and Company 1963.

- Penfield W. The difficult art of giving;: The epic of Alan Gregg. Little, Brown 1967

- Penfield W., The Mystery of the Mind: A Critical Study of Consciousness and the Human Brain. Princeton University Press,1975.

- Penfield, W., No Man Alone: A Neurosurgeon’s Life, Little, Brown & Co., 1977.

Editor’s note: see also Alan Blum, A bedside conversation with Wilder Penfield. CMAJ, April 19, 2011, 183(7) 745

JMS PEARCE, MD, FRCP, is emeritus consultant neurologist in the Department of Neurology at the Hull Royal Infirmary, England.

Leave a Reply