Sara Nassar

Cairo, Egypt

“They say that genius is an infinite capacity for taking pains.”1

– Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, A Study in Scarlet

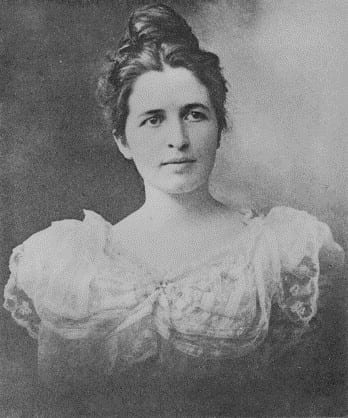

Dorothy Mabel Reed Mendenhall opened the doors of medicine at a time when women were considered incapable of managing this “gory” field. Although Reed’s eponymous Reed-Sternberg cell was a pivotal discovery for the diagnosis of Hodgkin’s lymphoma, little has been written about this remarkable woman and her contributions to the field of medicine.

Dorothy Reed was born in 1874 in Columbus, Ohio, the youngest of three siblings.2 Reed’s father died from complications of tuberculosis and diabetes when she was only six years old.2 Although she did not receive any formal education until the age of thirteen, she had already learned to read, write, draw, and paint3 before her mother hired a governess named Anna C. Gunning, who would play an important role in Reed’s educational beginnings. Reed pointed out in her autobiography: “Her [Anna] unflinching rules of doing well what was to be done . . . she ground into me habits of study which made it possible for me not only to go to college, but later to take up graduate work.”3

Reed attended Smith College where she discovered her passion for medicine.3 Following her graduation in 1895, she enrolled in science classes at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in order to fulfill the requirements of Johns Hopkins Medical School, which had just started accepting women.4 In 1896 Reed was one of very few women accepted at Johns Hopkins, the first of many challenges in the male-dominated field of medicine.2 Reed recalled: “In my first day in Baltimore a man said very casually, ‘Are you entering the medical school? Don’t,’ said he. ‘Go home.’ ‘Well, thought I, he must be crazy.’”3 Years later Reed would describe that man, Dr. William Osler, as “The greatest teacher I have ever known.”3 Reed obtained her M.D. in 1900 and was offered an internship under none other than Dr. Osler, an event which brought some unwanted troubles.3,4 Paul Woolley, a colleague of Reed’s, wanted her to pass the opportunity to him, threatening that otherwise he would leave Baltimore.3 Shocked by this bizarre request, the incident made Reed even more aware of women’s struggles for recognition and equal treatment.3 She unapologetically accepted Osler’s offer and later wrote, “In June 1900 I left Baltimore with high hopes . . . I had the satisfaction of having worked hard . . . so the reward of an internship under Dr. Osler seemed deserved.”3

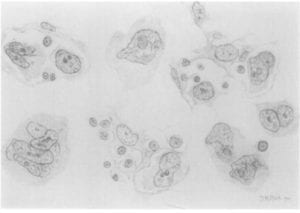

One year later she was offered a pathology fellowship in Dr. William Welch’s laboratory where she researched Hodgkin’s disease.5 During her fellowship, Reed identified what is now the pathological diagnostic hallmark of Hodgkin’s lymphoma, the Reed-Sternberg cell. Although the Austrian pathologist Carl Sternberg had previously described the same multinucleated cell in 1898, he was convinced that Hodgkin’s disease was a form of tuberculosis,6 which had been a common misconception for nearly a century since the discovery of the disease by Thomas Hodgkin. Tuberculosis and Hodgkin’s disease do, in fact, share some general symptoms such as night sweats, weight loss, fever, and lymphadenopathy,6 which lead to the misdiagnosis of many patients. By inoculating rabbits with lymph nodes from affected patients, Reed was the first to determine that tuberculosis and Hodgkin’s disease were distinct conditions.7 She was also the first to identify males and young adults as the groups most frequently affected by Hodgkin’s disease.8 Reed additionally noted the absence of an immune response to tuberculin in Hodgkin’s disease, and concluded that Hodgkin’s disease was not an infection but rather a “process.”7,8

The illustrious Sherlock Holmes used to tell Dr. John Watson, “You see, but you do not observe. The distinction is clear.”9 Dorothy Reed had both seen and observed. At the age of twenty-eight, she published her first paper titled “On the Pathological Changes in Hodgkin’s Disease, with Special Reference to its Relation to Tuberculosis.”5 Impressed by her work, Dr. Welch offered Reed an extension of the pathology fellowship. Feeling the weight of her family’s crippling financial status, Reed declined, stating that the wage was unsuitable and discussed the possibility of a future teaching position.3 Despite Dr. Welch’s support of coeducation, he explained that teaching positions had never been offered to a woman before.3 Feeling overlooked and alienated, Reed turned down the fellowship extension, which was a turning point in her career. Reed remarked: “May 30th, the very day I left Baltimore, was the lowest point of my life of 28 years . . . On that day I turned my back on all I wanted most and started to make a new life for myself.”3

Dr. Welch continued to believe in Reed’s potential and nominated her for a residency position in the pediatrics department at the Babies Hospital in New York City. She became the first resident physician there in 1903.3,4 Sadly, in the same year Reed’s sister died, leaving behind three children who were cared for by Reed.2 Taking on the responsibility of her sister’s children in addition to her mother’s finances had a substantial impact on her. Reed elaborated: “It [her situation] forged my character into iron, any sweetness I may have once had turned to strength, it made a woman of me in my teens, sent me into a profession . . . but one bad thing it gave was the fear of being left in want.”3

In 1906 Reed married Charles Mendenhall, whom she had met when she was a student in Baltimore.2,3 After marriage she postponed her career for eight years, hoping to build a family.2 Thereon, Reed remarked “I could not imagine life without husband and sons, though I hope for a future when marriage need not end a career of laboratory research.”3 Losing her first baby during delivery,2 followed by the death of her second child in an accident, left Reed depressed.3 However, by 1912 she had two healthy boys.5 In 1914 Reed decided to return to medicine, but was criticized by men in her profession who thought she had wasted her education.2 Nonetheless, she continued to strive in the field of public health where she developed an interest in women’s and children’s health. Reed wrote two books in this field: Milk: The Indispensable Food for Children published in 1918, and What is Happening to Mothers and Babies in the District of Columbia? published in 1928.2 At sixty years of age, Reed ended her professional activity when her husband became ill and later died in 1935.3 Dorothy Reed Mendenhall died of heart disease in 1964.2

“We were not wanted, in medicine as in every profession then and now a woman has to stand head and shoulders above a man to expect equal preferment,”3 wrote Dorothy Reed Mendenhall in 1934. Despite the many challenges women faced in medicine in nineteenth century America, Reed achieved a great deal and made invaluable contributions in the field of hematology.

References

- Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. 1985. A Study in Scarlet: A Sherlock Holmes Murder Mystery. London: Peerage Books.

- Parry, Manon. 2006. “Dorothy Reed Mendenhall (1874- 1964).” American Journal of Public Health 96, no. 5 (May): 789-789. https://dx.doi.org/10.2105%2FAJPH.2006.085902

- Jill Ker Conway. 1992 .Written by Herself: Volume I: Autobiographies of American Women: An Anthology. United States of America: Vintage Books.

- National Library of Medicine. 2003. “Celebrating America’s Women Physician: Changing the Face of Medicine.” Last modified June 03, 2015. Accessed January 04, 2020. https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_221.html

- Dawson, Peter J. 2003. “Whatever Happened to Dorothy Reed?” Annals of Diagnostic Pathology 7, no. 3 (June): 195-203. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1092-9134(03)00020-0

- Thakkar, Karan, Saket M. Ghaisas and Manmohan Singh. 2016. “Lymphadenopathy: Differentiation between Tuberculosis and Other Non- Tuberculosis Causes like Follicular

- Terezakis, Stephanie. 2015. “Dorothy Reed Mendenhall: Expression of a Pioneer in Hodgkin Disease.” International Journal of Radiation Oncology 92, no. 1 (May): 8-10.

- Zwitter, Matjaz, Joel R. Cohen, Anna Barrett and Elizabeth D. Robinton. 2002. “Dorothy Reed and Hodgkin’s disease: a reflection after a century.” Journal of the American Society for Radiation Oncology 53, no. 2 (June): 366-375. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0360-3016(02)02737-2

- Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. 1892. The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. London: George Newnes Ltd.

Image sources

- Dawson, Peter J. 2003. “Whatever Happened to Dorothy Reed?” Annals of Diagnostic Pathology 7, no. 3 (June): 195-203. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1092-9134(03)00020-0

- Source: Dawson, P.J. 1999. “The original illustrations of Hodgkin’s disease.” Annals of Diagnostic Pathology 3, no. 6 (December): 386-393. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1092-9134(99)80018-5. Also found in: Lakhtakia, Ritu and Burney, Ikram. (2015). “ A Historical Tale of Two Lymphomas, Part I: Hodgkin Lymphoma.” Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal 15, no. 2 (May): 202-206. PMCID: PMC4450782

SARA KAMAL NASSAR, BSc, MLS (ASCP)CM, earned a Bachelor’s degree in Biomedical Sciences in 2019 from the University of Qatar and is a board certified medical laboratory scientist. Sara currently lives in Egypt and plans to continue her academic journey.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest

Leave a Reply