Navanjana Siriwardane

Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, Canada

Amidst the fighting and chaotic nature of World War II, the need for proper blood banking was greater than ever. Millions of soldiers were dying without proper blood transfusions, and the cost of saving many lives was in the hands of the Red Cross. Dr. Charles Richard Drew was one of the first researchers to use plasma as a treatment for shock and blood loss.1 In addition, Drew also ameliorated and standardized methods of blood preservation, which was crucial for saving millions of lives during World War II. The methods discovered by Charles Drew are still utilized today by the Red Cross and have continued to help save millions of lives.1

Charles Richard Drew was born in 1903 to a middle-class African American family.2 Excelling in both athletics and academics, he won an athletic scholarship and aspired to be a surgeon.2 Because of racial segregation in the U.S., Drew studied medicine at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, where he fostered a stronger interest in surgery and bacteriology.3 Drew excelled in medical school and his passion for surgery lead him to apply for surgery residencies in the U.S. Drew wanted to continue research in transfusion medicine, but many American institutions continued to discriminate in their acceptance processes. However, Howard University was one of the few schools that had a progressively accepting view of African American students. Due to Drew’s excelling nature in athletics and his successful academic career, Howard hired him to teach first pathology and then surgery.3 His superiors praised Drew as being “intelligent” and “a very high type of man.”2 After his residency finished, Drew was able to work at the New York-Presbyterian Hospital to further his medical experience through research.

In 1938, Drew received a Rockefeller fellowship and began work on his doctorate at Columbia University, which was conducting research for proper blood banking at New York-Presbyterian Hospital.4 At that time, the possibility of the U.S. entering into war against Germany was looming. Blood banking was an important aspect of warfare, especially for the Royal Air Force, which was undergoing rapid expansion in response to German attacks. The British government had made a request to the Blood Transfusion Betterment Association (BTBA) in New York to collect and ship blood donations to England. The BTBA reached out to the U.S. government for assistance and consequently the American Red Cross started a program called Blood for Britain. The program aimed to collect blood donations to send to Britain3 and partnered with several New York hospitals such as New York-Presbyterian Hospital, which is where Drew and his colleague John Scudder were working.1

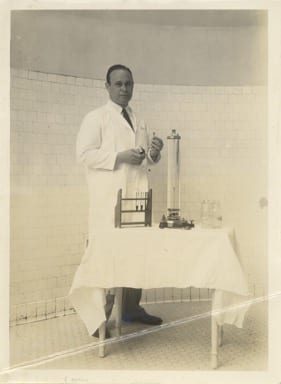

Before researching new methods of blood banking, Drew and Scudder considered the previous methods of blood preservation.1 During World War I, sodium citrate was used as an anticoagulant and whole blood was preserved with dextrose; however, this method only preserved whole blood for about a month.3 Another method was needed to maintain the blood being sent to Britain for a longer period of time. Drew’s research at Columbia University focused on preserving blood for clinical use,5 especially plasma, which could be maintained for one year with refrigeration. Plasma is abundant, carries nutrients and antibodies, and does not require the matching of blood types.4 With the help of Scudder, Drew worked on techniques such as centrifugation to separate red cells from plasma, as well as the best shape and material for storage containers. Each plasma sample was tested for contamination, refrigerated in sanitary containers, and tested again for contamination before it was deemed safe for clinical use. This blood program resulted in over 5000 litres of blood plasma being sent to Britain, saving thousands of lives and proving a successful medical innovation. Furthermore, the Blood for Britain program promoted bloodmobiles,5 which were mobile blood collection units that increased access for volunteers in the community. The bloodmobile is still used today and is an important aspect of blood collection for the Red Cross.

In 1941 Drew returned to Howard University where he became Chief of Surgery at Freedman’s Hospital.4 He decided to leave his work in blood banking, criticizing the policy of segregating and labeling blood from black donors. Since Drew faced numerous difficulties with racial discrimination in his medical career, he felt the need for equality in not just medicine, but in all aspects of life was crucial for the progress of society as a complex and diverse entity. In a letter, Drew stated: “I feel that the recent ruling of the United States Army and Navy regarding the refusal of coloured blood donors is an indefensible one from any point of view. As you know, there is no scientific basis for the separation of the bloods of different races except on the basis of the individual blood types or groups.”6

The remarkable achievements of Charles Richard Drew not only made him an acclaimed figure in blood banking history but improved the services of the American Red Cross. He also championed racial equality within medicine and American society. Dr. Drew exemplifies an educated mind who wanted a better system of equality. After Drew resigned, he returned to Howard University and became the head of surgery.5 Drew continued to teach surgery to African American residents and his students were some of the top performing in the country.7 Dr. Charles R. Drew not only changed the way we collect blood, but also carried a modern outlook on equality. After years of teaching at Howard University, Charles Richard Drew passed away at the age of forty-six in a tragic car accident.7 Without a doubt, Dr. Charles Drew has left an indelible mark on medical history. Not only did his research contribute to saving millions of lives, but his legacy as an outstanding surgeon, teacher, and researcher continues to be an inspiration to many.

References

- “Becoming ‘the Father of the Blood Bank,” 1938-1941 | Charles R. Drew – Profiles in Science.” U.S. National Library of Medicine. National Institutes of Health. Accessed January 2, 2020. https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/spotlight/bg/feature/blood.

- “Education and Early Medical Career, 1922-1938 | Charles R. Drew – Profiles in Science.” U.S. National Library of Medicine. National Institutes of Health. Accessed January 2, 2020. https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/spotlight/bg/feature/education.

- “Charles Richard Drew.” American Chemical Society. Accessed January 2, 2020. https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/african-americans-in-sciences/charles-richard-drew.html.

- “Charles R. Drew, MD.” Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science. Accessed November 13, 2019. https://www.cdrewu.edu/about-cdu/about-dr-charles-r-drew.

- “‘My Chief Interest Was and Is Surgery’–Howard University, 1941-1950 | Charles R. Drew – Profiles in Science.” U.S. National Library of Medicine. National Institutes of Health. Accessed January 2, 2020. https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/spotlight/bg/feature/my-chief-interest-was-and-is-surgery-howard-university-1941-1950

- Love, Spencie. One Blood: the Death and Resurrection of Charles R. Drew. The University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

- “Charles Richard Drew.” Science History Institute, December 4, 2017. https://www.sciencehistory.org/historical-profile/charles-richard-drew.

- “Blood Components.” Plasma, Platelets and Whole Blood | Red Cross Blood Services. Accessed January 2, 2020. https://www.redcrossblood.org/donate-blood/how-to-donate/types-of-blood-donations/blood-components.html.

NAVANJANA SIRIWARDANE is a first year Bachelor of Science student at Dalhousie University. Originally from Sri Lanka, she now lives in Prince Edward Island, Canada and hopes to pursue a future in medicine and research.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest

Leave a Reply