Mark Tan

Northwest Deanery, UK

|

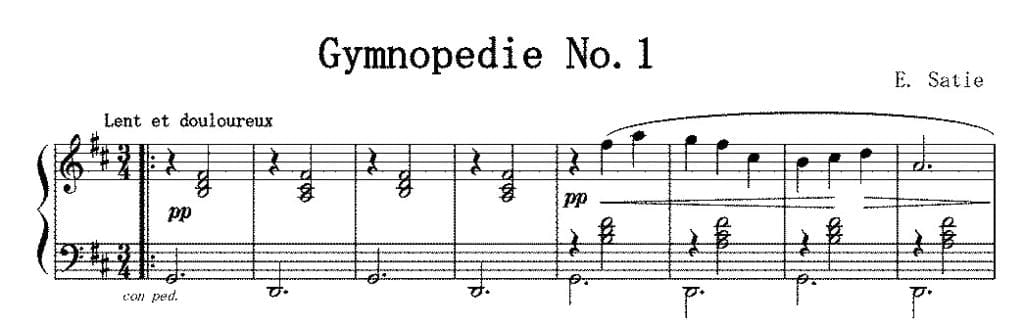

| First phrase of Gymnopédie. Erik Satie, 1888. Gymnopédie No. 1. Public domain |

Oblique et coupant l’ombre un torrent éclatant

Ruisselait en flots d’or sur la dalle polie

Où les atomes d’ambre au feu se miroitant

Mêlaient leur sarabande à la gymnopédie

[English translation]:

Slanting and shadow-cutting a bursting stream

Trickled in gusts of gold on the shiny flagstone

Where the amber atoms in the fire gleaming

Mingled their sarabande with the gymnopaedia.

– J.P. Contamine de Latour

The musical directions Lent et douloureux (slow and painfully) contrast with the relaxing melody of Erik Satie’s Gymnopédie. Or perhaps there is actually a way to find relaxation amidst pain.

Satie wrote Gymnopédie in 1888. The French gymnopédie is defined in music dictionaries as a nude dance by young Spartan maidens accompanied by song.1 This may be further traced back to the Greek gymnopaedia, an annual festival of naked (or unarmed) young men dancing.

The piece begins slowly and regularly, in waves of two major seventh chords. In Western music, major seventh chords often project the resolution of musical tension. The bass note sounds first, in a 3/4 time signature pattern, underpinning and signaling the start of the musical journey. The rest of the major seventh chord follows. The two chords are a perfect fourth apart, a pleasing interval to the ear; a permanent resolution that is free of tension and unbound by worries or inhibitions, as in the dance from which the title comes.

The musical direction of douloureux perhaps suggests the reflective mood in the music, which has its own tension in the form of a mildly dissonant melody riding above the repeating sequence of chords. This tension builds slowly, but frequently resolves at the end of short phrases.

It was the perfect choice of music for volunteer guitarist Leigh to play for sick patients in a high-dependency unit (HDU). She walked into the middle of the bay while playing, each step deliberate and calculated, rhythmic as the accompaniment. Yet there was a spring and sway in her step, the coyness and tension of musical dissonance. She faced the patient in bed two, and with a demure smile invited the patient to join her in their own gymnopédie. Their eyes engaged, the patient smiled; consent. Through music, both were transported beyond the confines of the HDU. Perhaps they danced on a fine sandy beach, with the sun warming their bodies and the scent of the sea breeze invigorating their minds. The patient appeared to have escaped the walls of the HDU, freed herself of her lines, and floated above the rails of her bed. For those two minutes she existed beyond the pain of a twenty-centimeter midline laparotomy wound, breathing deep, slow breaths, which her pain had not allowed just a few minutes earlier. But now, during their gymnopédie, she seemed to inhale the fragrance of the sea, rather than the HDU odors of feces and chlorine. The patient waved her arms with the music, imagining the excitement of each swing, turn, and pirouette. Each musical phrase imagined as a clasping couple with outstretched arms leaning back in preparation for the thrill of a spin. The heady feeling after a good spin remained while Leigh slowly made her way around the bay.

The effect was reproducible in bed three, and again in bed four. Even more astounding, it was not confined to the patients. The entire unit suddenly slowed down, then stopped. Conversation turned from complaining about daily grievances to chatting about music. The HDU bay became, with Leigh’s presence and music, a seaside lounge. The regular beeping of the monitors were waves rolling up on the shore, the bright lights a surrogate for the warming rays of the sun.

A nurse noted how beautiful the music was, while I reminisced on my days of performing on stage, and the feeling of intensity at the climax of a musical piece followed by the euphoria of resolution and audience applause. I found myself standing at the desk outside each bay, enjoying the live performance, while observing the noticeable catharsis of the patients from their gymnopédie with Leigh.

While music in ICU/HDU is a fairly recent development, the use of music in healthcare and healing stretches back for millennia. Historical evidence of music being used in conjunction with priestly rites, which often involved healing, has been depicted on ancient frescos dating to 4000 BCE.2 However, much earlier archeological evidence of musical instruments consisting of bone flutes originated around 40000 BCE.3

Both music and healing were attributed to the ancient Greek god Apollo. His son Asclepius is also well-known as the representative of healing. Key aspects underpinning ancient Greek understanding of health were represented by Asclepius’ daughters: Hygeia (hygiene), Iaso (recuperation), Aceso (healing process), Aegle (glow of health), and Panacea (universal remedy). These concepts have been immortalized into the medical arts through the opening lines of the Hippocratic Oath:

“I swear by Apollo physician, by Asclepius, by Hygeia, by Panacea, and by all the gods and goddesses, making them my witnesses, that I will carry out, according to my ability and judgment, this oath and this indenture.” – Hippocratic Oath

Apollo himself was credited with the invention of the lyre, considered to produce the most beautiful sounds by the ancient Greeks. This ancient instrument with the appearance of a small harp produces sounds through the plucking of strings, which vibrate and cause alternating compression of air molecules. An attached resonating box amplifies the vibrations, allowing the resulting sound to be louder and fuller. These waves land on the tympanic membrane in the ear, which itself mirrors the vibrations received. Neural processing of these signals result in the brain’s sensation of sound. Leigh’s guitar produces sound in an identical process to the lyre. The strings, held in tension across the neck of the guitar, traverse the large resonating box that amplifies the vibrations created by fingers striking the string. By pressing her fingers onto the fingerboard, the length of the string changes and thus the tone produced.

Through processes not entirely understood, music alters not only emotional states, but accelerates healing processes and complements many aspects of medicine. Pain relief and relaxation through music have been demonstrated in several scientific studies,4 but even the ancient Greek mathematician Pythagoras observed the emotional catharsis that occurs with music.5 Likewise, Plato recognized the power of music as a way of conditioning and curing the soul, which in his philosophy was intricately linked to the body. To him, music encompassed vocal and instrumental sound production, as well as body movements and dance.6 Leigh’s rendition of Gymnopédie ministered to the souls of the patients, which manifested in their bodies as analgesia and anxiolysis.

For the patients on the HDU that day, there was healing through both medicine and music. The holistic healing of Apollo was delivered through Asclepius and his daughters; the drugs of Panacea had pulled many patients back from the brink of death, allowing for the recuperation of Iaso. Hygeia, as promoted by the clean setting and habits of the HDU, helped prevent further infections and complications. Finally, as the gymnopédie drew to a close, each patient was left with the naked glow of Aegle, the healing process of Aceso complete at last. The beast of human affliction, for those minutes of gymnopédie, was utterly defeated by the lyre of Apollo, or in this case, the guitar of Leigh.

“Now then, putrefy here on the earth which nourishes people! Nor will you live any more as an evil affliction to mortals . . .” – Hymn for Apollo, Homer (translated by Rodney Merrill)

References

- Davis, M. E. (2007). Erik Satie. London: Reaktion.

- Conrad, C. “Music for Healing: From Magic to Medicine.” Lancet 376, no. 9757 (Dec 11 2010): 1980-1.

- Tuebingen, Universitaet. “Paleolithic Bone Flute Discovered: Earliest Musical Tradition Documented in Southwestern Germany.” www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/06/090624213346.htm.

- Lunde, Sigrid Juhl, Peter Vuust, Eduardo A. Garza-Villarreal, and Lene Vase. “Music-Induced Analgesia: How Does Music Relieve Pain?”. PAIN 160, no. 5 (2019): 989-93.

- Cramer, J.A. “Anecdota Graeca V1: E Codd.”. Oxford: Bibliothecae Regiae Parisiensis, 1839.

- Pelosi, Francesco. Plato on Music, Soul and Body. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

MARK ZY TAN, MBBS, BSc, MRCS, MRCA, is an Intensive Care Medicine and Anaesthetics Specialty Trainee in the Northwest of England. His interest in the medical humanities was ignited at Imperial College London during his medical studies. He has long been involved in performing arts, both in Singapore where he grew up, and in the UK where he has undertaken his medical training.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 12, Issue 1 – Winter 2020

Leave a Reply