Martin Duke

Mystic, Connecticut, United States

For more than two thousand years, the extraordinary blood-sucking abilities of the medicinal leech (Hirudo medicinalis) provided physicians with an unusual if not bizarre alternative to venesection, cupping, and scarification for blood-letting their patients (Figure 1). This therapeutic use of leeches was described in the writings of Hippocrates, Galen, Nicander of Colophon, Antyllos and others from Greco-Roman times, was commented upon in the Middle Ages by the great Arabian physician Avicenna (980–1037) in his Treatise on the Canon of Medicine, and thrived during the early nineteenth century due in part to the influence and almost vampire-like enthusiasm of the French physician Francois Broussais (1772–1838).

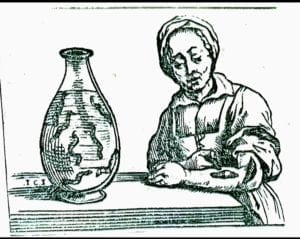

The eagerness and gusto with which doctors and patients applied leeches to treat a wide variety of ailments provided many opportunities for artists, satirists, and caricaturists to apply their talents. A woodcut in a volume compiled by the author Pierre Boaistuau entitled Histoires Prodigiéuses (1598) showed an obese man named Denis Heracleot who, according to the explanation in the text, was so fat that in order to lose weight he was compelled to place leeches on his arms and legs to pull out the grease.1

A print from 1845 entitled Les Amis by the well-known French printmaker, caricaturist, painter, and sculptor Honoré Daumier (1808–1879) portrayed a doctor telling a patient the following—“My dear fellow, I give you my word that you look very ill this morning . . . I’m going to apply thirty leeches to your epigastrium and if tomorrow I don’t find you improved, I’ll apply sixty.”2 A colored lithograph by the painter and caricaturist Charles Joseph Traviès (1804–1859) also showed a doctor, on this occasion prescribing another ninety leeches for a sick bedbound man while gentlemen crowded around the bed watching (c. 1827).3

In 1814, the English artist George Walker (1781–1856) published a book entitled The Costume of Yorkshire4 containing forty illustrations of the clothing worn by people of different professions in the county of Yorkshire, including one called “Leech Finders” (Figure 2). To catch the leeches, the women depicted in this illustration “promenade bare legged, with considerable picturesque effect, in the pools of water frequented by leeches. These little blood suckers attach themselves to the feet and legs, and [before they break the skin] are from thence transferred by the fair fingers of the lady to a small barrel or keg of water, suspended at her waist.”5 They are then collected and sold.

Not surprisingly, leeches also appeared in works of literature. Anton Chekhov (1860–1904), a writer and a doctor, found a place for them in his short stories and novellas. For example, in “Rothschild’s Fiddle,” Yakov brings his sick wife to the hospital where, feeling that she is not receiving the appropriate treatment from a feldscher (a doctor’s assistant), he asks him to “at least try the effect of leeches. I will pray God eternally for you.”6 He is not listened to and on leaving the hospital angrily says, “What an artist! He will let the blood of a rich man, but for a poor man grudges even a leech. Herod!”6 In another story, “The Muzhiks” (Peasants), a feldscher “applied leeches, and the old tailor, Kiriak, and the little girls looked on, and imagined they saw the disease coming out of Nikolai. And Nikolai also watched the leeches sucking his chest, and saw them fill with dark blood; and feeling that, indeed, something was coming out of him, he smiled contentedly . . . towards morning [he] died.” 7

One of the most significant works of Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), the nineteenth century German philosopher, scholar, and cultural critic, was his philosophical novel Thus Spake Zarathustra.8 While Zarathustra, a wise man and a prophet, is searching for those who are ready for his teachings, by chance he treads on a man who, during the conversation that followed, explains that “For the sake of the leech did I lie here by this swamp, like a fisher, and already had mine outstretched arm been bitten ten times, when there biteth a still finer leech at my blood, Zarathustra himself!”8 The leech had become part of their discussion, and Zarathustra invites the man to join him.

In a poem entitled “Resolution and Independence,”9 the English romantic poet William Wordsworth (1770–1850) described the solitary life of a leech gatherer, an old man whose job it was to gather leeches by wading bare legged in marshes and allow his legs to serve as bait for the parasites:

He told, that to these water he had come

To gather leeches, being old and poor:

Employment hazardous and wearisome!

And he had many hardships to endure:

From pond to pond he roamed, from moor to moor;

Housing, with God’s good help, by choice or chance;

And in this way, he gained an honest maintenance. . . .

He with a smile, did the his words repeat;

And said that, gathering leeches, far and wide

He travelled; stirring thus about his feet

The waters of the pools, where they abide.

“Once I could meet with them on every side;

But they have dwindled long by slow decay;

Yet still I persevere, and find them where I may.”9

The practice of medicine began to change rapidly during the second half of the nineteenth century. More specific therapies were becoming available and blood-letting with leeches was falling out of favor. As Wordworth pointed out in his poem, the leech population had also “dwindled long by slow decay.”9 In addition, marshes and areas that were once the natural habitats of leeches were now being put to other uses.

This was not, however, to be the final chapter for medical leeches in the history of medicine. Surgeons found a specific use for them in reconstructive surgery to help reduce swelling and congestion of skin flaps and implants.10 The anticoagulant factor in leech saliva, named hirudin, was isolated11 and was later used in some of the early studies on dialysis and the artificial kidney.12 And in place of the individual finders and gatherers of leeches of previous years wandering through the countryside, leech farms were developed to supply hospitals and researchers with medical leeches for clinical purposes and pharmaceutical studies. Is there more to come? It seems as if the relationship between humans and leeches that has existed for over two thousand years is not going to disappear quickly.

References

- Boaistuau P. Print (woodcut). In: Histoires prodigiéuses – Use of leeches to reduce weight, 1958. From National Library of Medicine, Unique ID: 101434586; Image ID: A029260.

- Mondor H, Daumier H. “Les Amis” (1845). In: Doctors and Medicine in the Works of Daumier. New York: Leon Amiel, 1970, p. 32.

- Traviès CJ. A doctor prescribes another ninety leeches for a sick bedbound man. Colored lithograph c. 1827. Wellcome Library no.16559i.

- Walker, George. The Costume of Yorkshire: illustrated by a series of forty engravings, being fac-similes of original drawings. London, 1814. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown. Call number: (Parsons) VWIP+ (Walker. Costume of Yorkshire). Rare Book Collection. The New York Public Library. Astor, Lenox, Tilden Foundations.

- Walker G. “Leech Finders,” Plate 35. In: Costume of Yorkshire: Leeds: Richard Jackson, publisher, 1885, p. 83. https://www.calderdale.gov.uk/wtw

- Chekhov A. Rothschild’s Fiddle. In: The Stories of Anton Tchekov (Chekhov), ed. Linscott RN. New York: The Modern Library, 1932, p. 442.

- Chekhov A. The Muzhiks. In: The Kiss and Other Stories by Anton Tchekhoff, tr. Long REC. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1915, pp. 312-313. (Harvard College Library. Bequest of Winward Prescott, January 27, 1933.)

- Nietzsche FW. Thus Spake Zarathustra; The Leech, Chapter 64, tr. Common T. New York: The Heritage Press, 1967, pp. 237-238.

- Wordsworth W. “Resolution and Independence.” In: The Poetical Works of William Wordsworth, ed. T. Hutchinson. London: Oxford University Press, 1920, pp.195-197.

- Whitaker IS, Rao J, Izadi D, Butler PE. Historical Article: Hirudo Medicinalis: ancient origins of, and trends in the use of medicinal leeches throughout history. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004; 42: 133-13

- Haycraft JB. On the action of a secretion obtained from the medicinal leech on the coagulation of the blood. Proc Roy Soc London 1884; 36: 478-487.

- Abel JJ, Rowntree LG, Turner BB. On the removal of diffusible substances from the circulating blood of living animals by dialysis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1914; 5(3): 275-316.

MARTIN DUKE, MD, FACP, graduated in 1954 from the New York University School of Medicine in New York City. He was in private practice in cardiology in Manchester, Connecticut, from 1963 to 1993. During this period, he served terms as Director of Medical Education and Chief of Cardiology at the Manchester Memorial Hospital and held a teaching appointment at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine. He is the author of two books and numerous medical articles.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest

Leave a Reply