| WOMEN IN MEDICINE |

| Published in November, 2019 |

| H E K T O R A M A |

| . |

|

The squalid streets of working-class Chicago in the late nineteenth century would have been something of a shock to the girl who grew up in a sheltered but educated household in Fort Wayne, Indiana. Her siblings all distinguished themselves as scholars, educators, and artists, encouraged by their mother, Gertrude, who taught all of her children, including her daughters, to achieve as well as to be of service. For Alice, this desire to be of service, a curious and active mind, and a wish for adventure and independence, formed her ambition to become a physician. More women were beginning to enter the field of medicine in the late 1800’s, but it was still by no means a common endeavor. While the Hamilton children had been taught literature and the classics at home, and the sisters later studied at a New England girls’ boarding school, Alice lacked the science background that would allow her to pursue a medical education. She worked to close this gap by studying with a nearby high school teacher, then entered a small, local medical college and tried to convince her dubious father of her intentions. She could have completed her studies at the “little third-rate” medical school and gone on to practice locally, but Alice Hamilton wished to receive a serious education as a laboratory scientist.

|

| IDA SOPHIA SCUDDER | ||||

|

|

||||

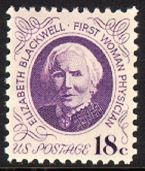

| ELIZABETH BLACKWELL, MD | ||||

|

|

||||

| ROSALYN YALOW: OPINIONS AND ACTIONS | ||||

|

|

||||

| MARIE ELIZABETH ZAKRZEWSKA: IMMIGRANT, PHYSICIAN, TEACHER | ||||

|

|

||||

| CICELY WILLIAMS AND KWASHIORKOR | ||||

|

|

||||

| FRANCES OLDHAM KELSEY | ||||

|

|

||||

| MADGE THURLOW MACKLIN: MEDICAL GENETICS | ||||

|

|

||||

| VIRGINIA APGAR: OUR JIMMY | ||||

|

|

||||

|

She was not famous and came from an unlikely medical career wellspring. Hazel Louise McGaffey (née Anderson) was born 21 August 1924 on her pioneer parents’ farm near Opheim, Montana, some of the last homesteading done in the 48 states. She was the second oldest of four children and recalls playing with prairie buffalo skulls. Her pets included Sparky, the coyote; she idolized Chief, the reliable draft horse, and their smart dog Shep, trained to bring the Herefords in from miles away. Her brother Arnold found a crumpled bugle believed to have been cast off from Sitting Bull’s retreating Sioux in flight from the Little Big Horn into Canada.

|

| . |

Hektorama

Leave a Reply