JMS Pearce

East Yorkshire, England

|

| Figure 1 |

Although Elizabeth Blackwell was portrayed on an 18 cent US stamp in 1974, curiously this was over a century after she graduated in medicine (Figure 1). Many remain unaware of her remarkable story as the first female Anglo-American physician, campaigner, and medical suffragette (Figure 2). [i]

She was born to a practising Quaker family in an old gabled house at Counterslip, near Bristol. Her father Samuel, a sugar refiner, was well-known in the 1820s for his opposition to slavery and his demands for reform in church and government. Her brother Henry was a spirited worker for women’s suffrage. Her younger sister Emily (1826-1910) became America’s second female physician. Having been rejected by Rush Medical College and Geneva College, Emily graduated from Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio in March 1854.

In 1832 the family’s sugar refinery burned down. At that time the family also faced hostility for their liberal views. They felt forced to moved to New York[i]; Elizabeth was aged only 11. Six years later they went to Cincinnati.[i] Her father had died of malaria in 1838 leaving the family almost penniless; Elizabeth displayed unusual courage and determination. She first opened The Cincinnati English and French Academy for Young Ladies. She then moved to Henderson, Kentucky in 1842, and in 1845-7 to North and South Carolina to teach in schools with her sisters. In Henderson, she befriended Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

|

| Figure 2 |

At first it was not a passion for science or medicine that drove Elizabeth Blackwell towards medicine: it was her friend, Mary Donaldson, dying from cancer. “She once said to me [Blackwell], ‘If I could have been treated by a lady doctor, my worst sufferings would have been spared me…. Why don’t you study medicine?’” But the known impossibility for women to gain admission to any medical school at first deterred Elizabeth. Women were considered not strong enough–mentally or physically–to face the unladylike demands of medical practice. In 1846 Blackwell wrote in her diary:

“I felt more determined than ever to become a physician, and thus place a strong barrier between all ordinary marriage and me. I must have something to engross my thoughts…”

Short of money, she made a living as a teacher. In 1847 she started to make applications to US schools of medicine. No fewer than twelve of them rejected her. At the end of her tether she applied to Geneva College (now Hobart College), a little-known institution in west-central New York State. With an introduction from Emma Willard, a noted promoter of female education, she met Joseph Warrington, a Quaker physician. Warrington commended her to the Dean, Charles Lee who, influenced by his students who favoured women’s entry to medicine, eventually accepted her in November 1847, observing: “This step might prove quite a good advertisement for the college.”

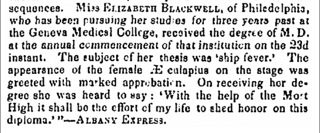

Local people and some male students ostracized and harassed her; she was even temporarily barred from classroom demonstrations. Her delicate, gentlewomanly constitution aggravated her disquiet and apprehension when confronted with anatomical dissections. She persevered and in January 23, 1849, ranked first in her class, with a thesis: The Causes and Treatment of Typhus, or Ship fever. She had become the first woman in the United States to graduate from medical school: an event which caught the public’s attention (Fig 3). Punch magazine noted:

|

| Figure 3 |

Young ladies all, of every clime,

Especially of Britain,

Who wholly occupy your time

In novels or in knitting,

Whose highest skill is but to play,

Sing, dance, or French to clack well,

Reflect on the example, pray,

Of excellent Miss Blackwell!.

Within a few years twenty other women graduated from American medical schools.

However, she was unable to get work in the USA and in desperation went to Paris. But again, meeting the same hostility to women doctors, she reluctantly enrolled in a midwives’ course at La Maternité, an obstetric hospital. Disaster struck on 4 November 1849. Whilst syringing the eye of a patient for a virulent infection (purulent ophthalmia), some of the water spurted into her left eye causing a suppurating infection; probably from sympathetic ophthalmia, she lost sight in both eyes. Eventually a surgeon had to remove her left eye, and sight slowly returned in the other.

A year later, visiting London, she met the brilliant, kindly surgeon, Mr. (later Sir James) Paget (1814-1899), celebrated for his descriptions of osteitis deformans and for Paget’s disease of the nipple. Paget helped her to gain entry as a postgraduate into St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in 1850. She was the first woman to be accepted in a London medical school. [iv]

Elizabeth Blackwell returned to America a year later, but again failed to obtain a hospital post. She rented an office at 44 University Place, in Jersey City, but her practice was slow to develop. In 1854 Elizabeth, with her sister Emily and Dr. Marie Zakrzewska (who founded the New England Hospital for Women and Children), established the New York Dispensary for Poor Women and Children supported by generous Quaker donations. She became Professor of Hygiene. Fire again played its hand when the infirmary was burned down. In May 1857 the dispensary was incorporated as the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. It was the first American hospital to be staffed completely by women.

In January 1859, she undertook a year’s lecture tour of Great Britain, and then returned to the American women’s college. During the American Civil War, Blackwell trained many women to be nurses to assist the Union Army.

In 1869, angered that in England women were still unable to gain general acceptance, she left sister Emily in charge of the New York College and returned to London.[v] With Sophia Jex-Blake (1840 -1912) and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (1836-1917), whom she had met in 1859, she opened the Women’s Medical College. She lectured at the new London School of Medicine for Women, renamed in 1918 the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital, and accepted the Chair in gynecology in 1873. She was the first woman to obtain a place upon the English Medical Register, in 1859. She continued in practice, and lectured widely on education and public health until she retired.

|

| Figure 4 |

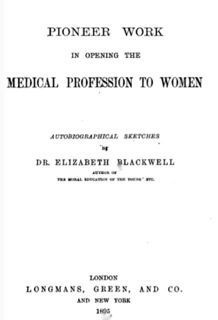

But she remained active in the Women’s Rights Movement and was a popular lecturer and prolific writer. Importantly, she was not antagonistic to men in Medicine but rather sought an independent equality for women. In 1907, an injury forced her to retire. But she continued writing. Among her texts are: The Religion of Health (1871), Counsel to Parents on the Moral Education of Their Children (1878), The Human Element in Sex (1884), her autobiographical Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women (1895)(Fig 4.), [vi] and Essays in Medical Sociology (1902).

Inspirational determination and perseverance are the hallmarks of the life of Elizabeth Blackwell. She worked untiringly for the causes in which she believed and lived to see many of her views eventually accepted. She once remarked: “If society will not admit of woman’s free development, then society must be remodeled.” Her resolute perseverance is reflected in her comment that: “The idea of winning a doctor’s degree gradually assumed the aspect of a great moral struggle, and the moral fight possessed immense attraction for me.” Paradoxically she said she had hated everything connected with the body, could not bear the sight of a medical book, and that her favorite studies were history and metaphysics. But her prime aim was not feminism as we know it, but a quest for equal opportunity for women. Her courageous zeal showed other women the road to success; those who followed readily acknowledged their debt to her.

She organized the Women’s Central Association of Relief and the United States Sanitary Commission. She is remembered by the Blackwell Medal, established in 1949 and given to women with outstanding achievements in Medicine. The inaugural annual Elizabeth Blackwell Public Lecture (established for ‘a distinguished woman in the field of public health or preventative medicine’) was given on 26 November 2014 by Dame Sally Davies, FRS, Chief Medical Officer for England. The Elizabeth Blackwell Institute for Health Research was officially opened in July 2013 at the University of Bristol.

Elizabeth never married although she was close to and enjoyed extensive discussions with Alfred Sachs from Virginia. But she adopted Katherine (Kitty) Barry, an orphan of six. The two forged an excellent relationship and Kitty was devoted to her ‘Auntie Blackwell’ to the end of her days. On holiday in Kilmun, Scotland in 1907 Elizabeth fell down the stairs sustaining serious injury from which she never fully recovered. She died on 31 May 1910 at her home in Hastings in Sussex, probably after a stroke. She was buried in June 1910 in Saint Mun’s churchyard at Kilmun, a place she loved in Argyllshire.

Scorned and obstructed in the United States, Blackwell struggled but forged opportunities and eventual success in England. But for women doctors progress was tardy. By the end of the nineteenth century they constituted only five percent of the profession, a proportion that has increased but slowly. Now, equity for women more or less prevails. Elizabeth Blackwell’s trials have not been in vain.

References

- Kline, Nancy. Elizabeth Blackwell: A Doctor’s Triumph. Berkeley, CA: Conari Press, 1997

- Roth, Nathan. The Personalities of Two Pioneer Medical Women: Elizabeth Blackwell and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 1971;47(1):67-79.

- Wilson, Dorothy Clarke. Lone woman: the story of Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman doctor. Boston, Little Brown. 1970.

- Morantz-Sanchez Regina. Sympathy & Science. Women Physicians in American Medicine. Chapel Hill & London, University of North Carolina Press. 1985

- Somervill Barbara A. Elizabeth Blackwell: America’s first female doctor. Pleasantville NY, Gareth Stevens Publishing.

- Blackwell E. Opening the medical profession to women : autobiographical sketches Longmans, Green, 1895.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of science and medicine.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Spring 2017 – Volume 8, Issue 4

Winter 2016 | Sections | Women in Medicine

Leave a Reply