Anne Jacobson

Oak Park, Illinois, United States

|

| Alice Hamilton in 1919 |

It is a gritty, frozen day in winter-weary Chicago, one that does little to inspire action; perhaps least of all a frigid walk around the salty, potholed neighborhood. In a month or two a lunchtime walk would be a welcome idea; university students will gather on park benches, and the staff of four busy hospitals will step out for a moment or two of sunshine. This area looks remarkably different than it did a century ago when Dr. Alice Hamilton lived and worked here, when the residents of its tenement-lined streets were living and dying in occupations and communities that made them sick. Dr. Hamilton, who would one day be known as the founder of the field of industrial medicine, was a woman of action; so although the day invites another cup of coffee instead of a frigid ramble, I am taking my mental conversation out to the streets where she lived and worked one hundred years ago, and the neighborhood where I now make my professional home.

The squalid streets of working-class Chicago in the late nineteenth century would have been something of a shock to the girl who grew up in a sheltered but educated household in Fort Wayne, Indiana. Her siblings all distinguished themselves as scholars, educators, and artists, encouraged by their mother, Gertrude, who taught all of her children, including her daughters, to achieve as well as to be of service. For Alice, this desire to be of service, a curious and active mind, and a wish for adventure and independence, formed her ambition to become a physician. More women were beginning to enter the field of medicine in the late 1800’s, but it was still by no means a common endeavor. While the Hamilton children had been taught literature and the classics at home, and the sisters later studied at a New England girls’ boarding school, Alice lacked the science background that would allow her to pursue a medical education. She worked to close this gap by studying with a nearby high school teacher, then entered a small, local medical college and tried to convince her dubious father of her intentions.

She could have completed her studies at the “little third-rate” medical school and gone on to practice locally, but Alice Hamilton wished to receive a serious education as a laboratory scientist. In 1892 she enrolled at the University of Michigan, which was at the forefront of standardized and rigorous medical training, and also ahead of its time in its acceptance of women as medical students. She excelled in her classes, and although she planned to be a bacteriologist, she also believed that a foundation in clinical medicine would be of use. She pursued an internship first at Northwestern Hospital for Women and Children in Minneapolis in 1893, then transferred later that year to the more prestigious New England Hospital for Women and Children. As part of her work in Boston, she paid home visits to ethnic neighborhoods, tenement homes, and brothels, giving her a first glimpse into the needs of the working poor and foretelling the ways in which her talent for science would ultimately be of use in the most vulnerable communities.

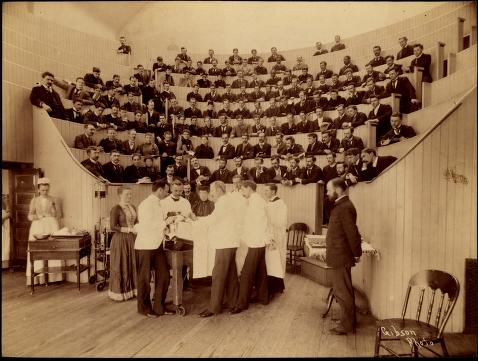

|

| Demonstration in medical school amphitheater (Alice Hamilton, 3rd row, 8th from left), ca. 1893. University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library. |

Hamilton wished to pursue a PhD at Johns Hopkins, but while women were allowed to attend classes there, they could not complete a doctoral degree. With a fervent wish to continue her scientific training, she sailed to Europe in the fall of 1895 with the hope of training with the great German scientists of the day. While her gender prevented her from fulfilling that plan, she was able to pursue limited studies in pathology in Leipzig (she was barred from attending autopsies) and cell biology in Munich (where she was not allowed to conduct animal experiments). Finally she was allowed to work fully and freely with Ludwig Edinger, with whom she studied the olfactory system of bony fish. The friendship she developed with Edinger and his wife, Anna, a social welfare leader, along with this early travel experience to Europe, would lay the foundation for many future trips in the pursuit of professional knowledge and social causes.

Returning to the United States the following year, Hamilton would further her work in science at Johns Hopkins, even though she was still not allowed to complete a degree there. She worked with Simon Flexner, publishing papers on the pathology of tuberculous stomach ulcers and neurogliomas of the brain. She counted some of the great leaders in American medicine, such as William Welch and William Osler, among her close professional colleagues. With strong training, research, and professional recommendations, in 1897 she accepted a position as professor of pathology and director of the pathology lab at the Woman’s Medical College of Northwestern University in Chicago. However, the women’s school was in decline, had limited resources, and did not meet Hamilton’s professional standards. Pathology had only been taught by lecture at the college, so Hamilton set about procuring her own lab specimens, first from colleagues at Rush Medical College, then from autopsies performed at Cook County Hospital.

Professionally frustrated and personally isolated, and with a burgeoning awareness of social reform movements, Hamilton moved to Hull House, which had been established by Jane Addams as part of the settlement house movement in turn-of-the-century America. Located on the west side of Chicago, in Hamilton’s words “a region of unrelieved ugliness,” Hamilton, Addams, and their fellow Hull House residents were educated women and men who not only provided social, educational, and healthcare opportunities for poor and immigrant communities, but also became neighbors and allies by living among the people they served. Hull House would remain Hamilton’s grounding influence and home base for more than thirty years, spending at least a portion of her time there even after she had moved on to hold positions of national and international importance.

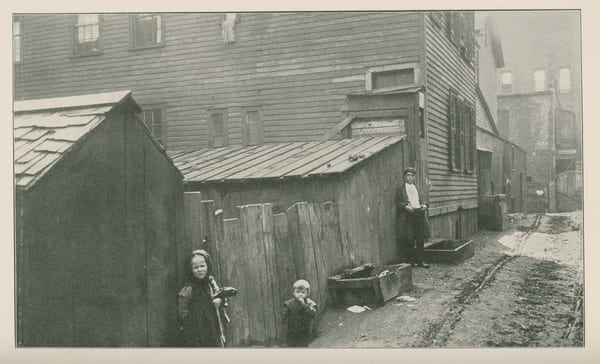

|

| From Tenement Conditions in Chicago. Robert Hunter, 1901. The Newberry Library, Chicago. |

Hull House remains standing on the west side of Chicago, now a museum and reminder of the important work of people like Alice Hamilton who sought to achieve but also to serve. This area is still a center of learning and of service, a hub of higher education and healthcare. As I continue walking in Hamilton’s old neighborhood on this winter day, (admittedly grateful that the air no longer smells of the infamous stockyards nor the streets flow with raw sewage), I consider another professional connection. In 1902 Hamilton accepted a position as a bacteriologist at the Memorial Institute for Infectious Diseases, which was opened that year by Dr. Ludvig Hektoen. Hektoen, a pathologist and bacteriologist, was an important figure in Chicago and national medical circles, advanced research and standards in his fields, and is the namesake of both the Hektoen Institute of Medicine and the Hektoen International Journal of Medical Humanities. Hektoen would be an influential figure in Hamilton’s career. In this same year she was able to join her formidable research abilities with her settlement house life, playing a pivotal role in determining and eradicating the source of a typhus outbreak in Chicago and publishing her results the following year.

In the years that followed, continuing both her work at the Memorial Institute and at Hull House, Hamilton became more interested in the diseases she witnessed in neighborhood residents that were due not only to poverty and poor public health infrastructure, but more specifically those that were acquired by working in industry. In 1908 the governor of Illinois appointed Hamilton, along with eight men, to a commission investigating occupational diseases. Out of this commission emerged the need for a statewide survey of hazardous exposures in industry, and Hamilton was chosen to be the medical investigator. In addition to leading the survey, she personally conducted the portion that investigated lead poisoning, which was widespread and devastating for workers in a variety of industries of the era, causing nerve damage, encephalopathy, and premature senility in its most advanced stages. Her approach to research was both methodical and innovative; she gained access to factories and workshops through straightforward and respectful conversations with foremen and company owners, observed the workers performing their jobs (sometimes performing the work herself), interviewed families and community members, tracked down hospital records and examined patients, and kept meticulous records of her findings. Reporting on area industries at the same time as the famous muckraking reporters, such as Upton Sinclair in Chicago’s stockyards and meat packing plants, Hamilton took a different approach to her work. She advocated strongly for workers’ health and safety, calling out members of her own profession when needed (such as company-employed physicians who ignored or falsified workers’ conditions), but also believed that owners and industry leaders would truly want to improve conditions for their employees once they were aware of them. She would continue to use this hands-on, straightforward approach to each of the “dangerous trades” she would examine in her career.

|

| Hull House, Chicago, 1910 |

Hamilton’s lead study, and the broader findings of the survey under her leadership, compelled Illinois to pass one of the first occupational disease laws in the nation in 1911. Her success brought about a position with the U.S. Bureau of Labor to investigate lead industries nationwide. By the time a full-fledged Department of Labor was established in 1913, she had become known as the top physician researcher in her field. She would go on to direct investigations and make vital contributions to occupational safety in industries as diverse as stonecutting (silicosis), matchstick making (phossy jaw), hatmaking (mercury poisoning), wartime ammunitions plants (nitrous oxide poisoning), the introduction of the pneumatic jackhammer in mining (spastic anemia of the fingers), viscose rayon in textiles (paralysis and insanity from carbon disulphide poisoning), and steel (carbon monoxide poisoning).

In 1919, Alice Hamilton became an assistant professor of industrial medicine at Harvard Medical School, the first woman faculty member at Harvard University. Her appointment was met with some stalwart resistance, and she was not allowed to receive football tickets, enter the Harvard Club, or sit on the platform at graduation. She resolutely continued her work, however, teaching for part of each year and continuing her industrial field investigations in the other part. She continued to make trips to Europe; both to participate in professional conferences and investigate industrial practices, as well as to participate with other Hull House activists in the push for the adequate feeding and care of civilians after two world wars. She would be invited to make an inspection of factories in Soviet Russia, be appointed to the Health Committee of the League of Nations, and participate in the President’s Research Committee on Social Trends. She received a National Achievement Award from Eleanor Roosevelt in 1935, was awarded the prestigious Lasker Public Service Award in 1947, and was named TIME magazine’s “Woman of the Year” in Medicine in 1956. She was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1973, and in 1987 the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health dedicated its research facility to her.

Hamilton died in 1970 at the age of 101 in the rural Connecticut cottage she shared with her sister. As I stroll through the noisy, urban Chicago neighborhood where she made her professional start, I think about how she sought out and embraced the hidden beauty in impoverished places, empowered vulnerable people through careful listening and observation, and discovered her own strength by venturing into the dangerous trades. She earned positions of power and influence by observing a need, immersing herself in the experience, meticulously piecing together the underlying problem, and tirelessly advocating for its solution. Through her combination of intelligence, humility, and courage, she both advanced the field of industrial and occupational safety, and elevated the integrity of American medicine.

References

- Hamilton, Alice. Exploring the Dangerous Trades. Boston, 1943.

- Sichern, Barbara. Alice Hamilton: A Life in Letters. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2003.

ANNE JACOBSON, MD, MPH, is a family physician, writer, and the associate editor of Hektoen International. Her published works may be found in JAMA: A Piece of My Mind, in the anthology At The End of Life: True Stories About How We Die (In Fact Books, 2012), Hektoen International, and The Examined Life Journal.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 15, Issue 2 – Spring 2023

Winter 2019 | Sections | Women in Medicine

Leave a Reply