Amer Toutonji

Charleston, South Carolina, USA

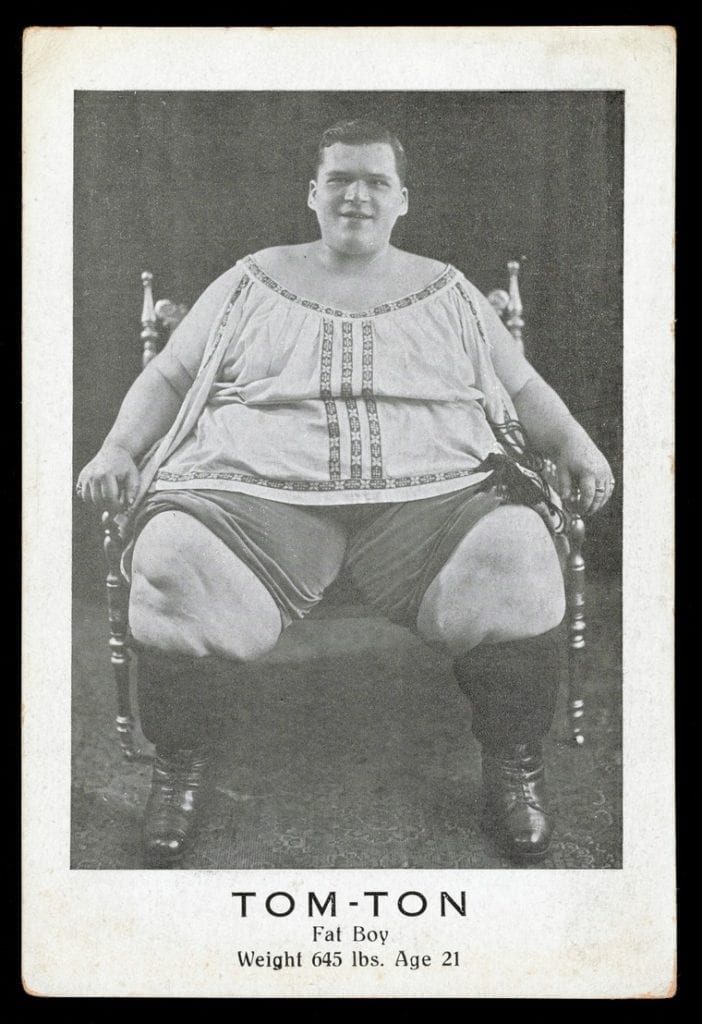

An early bird, Brian wakes up no later than 5:30 am to get on with the first meal of the day: twelve eggs and ten sausages, or their equivalent. Most recently weighing in at 530 pounds, Bryan, or Bull, as he likes to be called, is constantly outgrowing his clothes and exceeding the limits of commercial scales. It is an expensive lifestyle to say the least—financially, physically, and socially. However, unlike many seemingly healthy lives, Bull’s is a truly happy one, and not because of the abundance of the savory and sweet as one might imagine. Make no mistake; that is hard work. Instead, Bull has a loving family, a successful career, and a creative comic on social awareness that attracts many followers. One day though, Bull will come to a serious crossroads in his life and will walk into your clinic for medical advice. As a healthcare provider, how will your encounter with Bull unfold?

Bull’s story is a real life example of the clash of moral constructs often encountered in healthcare. In order to provide healthcare that is centered on patients’ individual philosophies of life and what they find meaningful, healthcare providers must be able to suspend judgment and connect genuinely with their patients. This requires healthcare providers to patiently inspect and reassess their beliefs about health and then to invite patients to openly explore and express theirs.

Societal values are often transferred through praise and condemnation, both direct and indirect. They are also transferred through the observation of people with whom we have a positive affinity. However, rarely do we question the moral roots of these values. In fact, are there any universal moral obligations? Is there a moral obligation to be healthy, to be ambitious, to create a family, or to be monogamous?

The term “moral” is concerned with the concept of right and wrong, good and bad. These judgments are largely based on religious teachings. Growing up as a Muslim in Lebanon, I was taught that people do not own their bodies. Instead, bodies are entrusted to us and should be well maintained. Therefore, given that specific belief, staying in good shape was the right thing to do. Others might argue from a “common sense” or an evolutionary perspective that “it does not feel good to carry around a lot of weight” or that “it is deadly.” These probably are true, but then right and wrong simply become instinctual drives of reward, aversion, and survival, none of which have an inherent moral value. On this basis, I argue that there are no universal moral obligations and that morality is contingent on our personal beliefs and values.

“I agree, but that still does not mean I shouldn’t practice medicine according to my beliefs and values,” said a colleague of mine. This made sense to me, but it is not an effective method. If quality of life is the primary concern, the patient is the one to choose what quality means. However, if being healthy is the primary concern and the doctor has specific beliefs about what healthy is, it is best to be clear about the treatment philosophy and offer the patient a referral if need be. Win-win. No hard feelings. Yet before doing so, doctors must also examine their own values. For example, consider the following sports: American football, boxing, auto racing, and others. Many believers in universal truths about health and followers of the maxim “do no harm” are also hardcore sports fans, despite their knowledge of the accidents and detrimental health outcomes sustained by some of these athletes. Why is it okay to accept the inevitable harm incurred in sports but not in other ways . . . in Bull’s way?

Despite my belief that what Bull does is not a matter of righteousness, if he walked into my clinic I would at least want to understand his motives and make sure that he does as well. I believe my role as a future healthcare provider is not to set the goals myself, but to guide patients to set their own goals based on a strong understanding of what matters to them as well as a strong understanding of their health issues. One way I like to connect with what matters to me is through understanding my motives using Viktor Frankl’s framework, described in his book Man’s Search for Meaning. Note, however, that many other frameworks on needs, desires, and motives exist and can be utilized to facilitate self-exploration.

Unlike Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler, Frankl did not believe that people are fundamentally driven by the will to pleasure or the will to power. What gave him the strength to survive the Nazi camps was the will to meaning. Only after one fails at finding meaning do they resort to other pursuits. According to Frankl, meaning can be found in three ways: in creation and service, in appreciation, and in honoring one’s suffering. Note, however, that Frankl did not claim to understand the ultimate meaning of human existence. He says that, like a movie, the ultimate meaning of life might not reveal itself until the very end, if at all. Frankl was instead speaking about an earthly and immediate feeling, a deep sense of fulfillment and connection with life, work, and the people we care about.

Is Bull’s lifestyle driven by pleasure, power, or meaning, or possibly a combination? This only matters as a method to probe for what matters most to him and not to judge the value of his actions or beliefs. This might also be applied to our own major life decisions. Was the decision to study medicine made out of curiosity, a drive for prestige and money, or to ultimately be of great service to a cause? If decisions are made primarily for curiosity (pleasure) or convenience (prestige & money), a person may be more likely to quit when things get difficult, and that might be the right thing to do. However, if there is a meaning connected to the journey, or a calling, the struggle feels worth it and might itself be a source of fulfillment.

Understanding patients’ motives provides the healthcare provider with powerful information that can be used to help them find new ways of generating meaning. For Bull, by first assigning the right motives to the behavior, one can decide to shift focus to a higher motive—meaning—or to explore healthier options that resonate equally or even more strongly with the same motive.

Putting aside personal beliefs, whether by pondering morality or inconsistencies, is crucial in allowing the healthcare provider to create a safe space for the patients to genuinely open up and connect with their motives, desires, and needs. Only then can patients mindfully participate in exploring treatment options and lifestyle changes that serve their individual life philosophies.

AMER TOUTONJI was born and raised in Lebanon. There, he went to the American University of Beirut for undergraduate studies in Biology, followed by two years of medical school. Amer later transferred to the Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP) at the Medical University of South Carolina where he is currently pursuing a PhD in Neuroscience studying neuroinflammation in stroke and traumatic brain injury. In the future, Amer hopes to join a combined neurology-psychiatry residency and pursue a career as a clinician, researcher, and educator.

Leave a Reply