Camille Kroll

Chicago, Illinois, USA

|

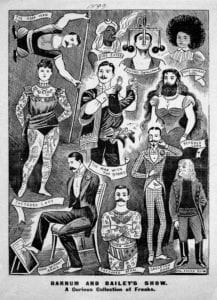

| An advertisement for the Barnum and Bailey circus, of which P.T. Barnum was a cofounder Credit: Wellcome Collection License: Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) terms and conditions |

Exalted showman P.T. Barnum was thrilled when he discovered Joice Heth, a severely disabled elderly slave woman. In grotesque detail, he assessed the value of his first sideshow acquisition with relish:

I was favorably struck with the appearance of the old woman . . . She might almost as well have been called a thousand years old as any other age . . . Former disease or old age, or perhaps both combined, had rendered her unable to change position…She was totally blind, and her eyes were so deeply sunken in their sockets that the eyeballs seemed to have disappeared altogether. She had no teeth, but possessed a head of thick bushy gray hair. . . . The nails upon [her left] hand were about four inches in length.1

Joice Heth’s deformities launched Barnum’s career in 1835 after he began displaying her as George Washington’s 161-year-old nurse, which Barnum certified by providing false medical documentation of her age. Barnum then extended Heth’s commodification even into death with a public autopsy, a frequent practice of the time usually reserved for the corpses of the poor, criminals, and African Americans.2

P.T. Barnum’s sideshow was one of many in the 1800s exhibiting bodies that were considered monstrous. First providing public entertainment as early as the 1600s, these “freak shows” reached the height of their popularity in Europe and America in the nineteenth century, a time during which the public display of the monstrous “Other,” including criminals, the deformed, and the insane, was used to reaffirm the social and natural order and demonstrate the dangers of transgressing it.3 Michel Foucault defined the monstrous individual as embodying “the transgression of natural limits, the transgression of classifications . . . and [the transgression] of the law.” 4 The visual spectacle of the monstrous served a performative process by which the self and the freakish “Other” were defined, what scholar David Hevey terms “enfreakment.”5 Displaying deviance publically provided a feeling of normalcy to the viewer while also serving as an agent of social control by defining what should be viewed as abnormal.

The nascent field of modern medicine often served to perpetuate this narrative of “Otherness” by pathologizing individuals with physical differences. Physicians partook in the exhibition of unusual bodies, such as the famous display of Joseph Carey Merrick, shown as “The Elephant Man,” to the Pathological Society of London on December 2, 1884.6 The surgeon Sir Frederick Treves, who would eventually advocate for Merrick to live the remainder of his days in the London Hospital, recounted that “at no time had I met with such a degraded or perverted version of a human being as this lone figure displayed.”7 Deceased sideshow performers, including Merrick, were often sold as anatomical specimens for future study and were displayed to serve as a public reminder of their physical transgression. While the fields of pathology and teratology did advance because of the study and dissection of these bodies, the term “monster” was widely used throughout the nineteenth century to describe infants born with congenital disabilities. Physicians even advised pregnant women to avoid attending sideshow performances because of concerns that monstrous births were caused by viewing lusus naturae—freaks of nature.8

Sideshow curators, in turn, benefited from the budding legitimacy of the medical profession and, like P.T. Barnum with Joice Heth, often advertised that medical professionals had examined their performers and confirmed that they were indeed rare and genuinely odd. Disability studies scholar Robert Bogdan classifies most sideshow performances as falling into “the exotic mode” or the “aggrandized status mode.”9 In the former, many of the performers were advertised as freakish savages solely because of their non-white and thus purportedly inferior status. The latter displays often depicted the sideshow performers as highly educated and even aristocratic, qualities that would normally elevate their status if not for their physical anomalies. Both performance modes allowed audience members to reaffirm and find comfort in their own normalcy. During the performance, a physician—or an actor playing a physician—often offered a brief medical discussion of the performer’s deformity to add educational appeal and assuage any guilt the viewers might have for attending the show.

|

| A handbill advertising the medical element of the sideshow display of conjoined twins Millie and Christine McCoy (1851-1912) Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine. Creative Commons, Public Domain Mark |

The popularity of the quintessential freak show declined in the early- to mid-twentieth century, in part due to the medicalization of physical differences as pitiable maladies needing a healer’s touch rather than as incurable monstrosities. Although physicians may have previously examined sideshow performers in the context of their potential research or entertainment value, the display of people with physical differences shifted from the public sphere to the medical one as physicians began viewing disabled individuals as patients needing treatment, often surgical in nature.10 The injuries of World War I also created a new understanding of disability. Suddenly, the afflicted individuals were no longer safely removed and otherized on a stage or in a cage. Disability had become an intensely personal experience as fathers, brothers, and husbands returned from the War forever physically changed.11 Coupled with a burgeoning national sense that it was shameful to gaze upon the anatomically unusual, bourgeois sensibilities of self-regulation, hygienic superiority, and a fear of genetic contamination propelled by the eugenics movement led to sideshows falling into disrepute.12 While these shows had once provided an opportunity for class divides to dematerialize as rich and poor joined against “the Other,” these public spectacles were now classified as lowbrow.

Yet the public’s desire to look at abnormal bodies never truly disappeared. Similarly, medical professionals have continued to define what should be considered abnormal both on a daily basis in their clinics and, through a much more public outlet, by appearing in medical reality shows ranging from plastic surgery programs to documentaries covering the separation of conjoined twins. While these programs are clearly aired for their entertainment value, much like historical sideshows, they are legitimized through a purported message of medical education and health advocacy.

The goal of the British show Embarrassing Bodies, for example, is “to encourage people to address potentially embarrassing health issues.”13 But what should be considered embarrassing? Ultimately, the show’s physicians define this by deciding who is featured. In one episode, a nineteen-year-old presented with slightly protruding labia minora that were not physically painful but aesthetically caused her shame. After a short discussion with her, the physician immediately recommended a labiaplasty as the only reasonable option because “it was getting her down so much.”14 The comments on the show’s site and on forums discussing the show after this episode revealed that many young viewers did not realize this was a problem that they should have even considered embarrassing but were now acutely aware of their own supposed abnormality. One viewer lamented, “I’ve always thought I had normal labia, but according to this programme (and in comparison to that woman) then I must be hideously abnormal.”15 The show’s physicians have often uncritically portrayed women’s concerns about the size of their breasts, labia, and laryngeal prominences (i.e. Adam’s apples) as medical conditions necessitating treatment, just as the toenail fungus and tonsillitis in other episodes required medical intervention.

Shows such as TLC’s My 600 Pound Life16 similarly encourage the audience to view the featured individuals as mere bodies, evoking sideshow images of “The Elephant Man” or “The Bearded Woman.” The show also employs a “this could be you” scare tactic to allegedly educate the audience on the dangers of obesity. The audience is asked to read itself as “normal” against the abnormal “Other.” Yet viewers are also encouraged to examine their own bodies and ask, “Wait. Should I be embarrassed too?” When the boundary between the self and the “Other” is blurred, the viewer may suddenly find that he or she occupies a liminal space between the safety of constructed social order and the abject Other.17 The cognitive dissonance created by recognizing oneself in the social outcast implores the anxious spectator to redouble efforts to shun the perceived monstrousness in order to buttress his or her own identity.

While these shows may say they aim to educate by attracting viewers through sensationalism, they ultimately reinforce pathologization of differences and notions of medical paternalism. Only the doctors on these shows can make the patients normal again. The American plastic surgery show Botched showcases patients who attempted to obtain societal norms of physical beauty and then accidentally transgressed them. Although the show educates on the possible negative outcomes of plastic surgery, it also casts the featured doctors as the patients’ saviors, gently chiding the patients as they “fix” them. The show pays patients an appearance fee that covers a portion of their medical bills.18 In turn, patients must be willing to publicly expose themselves as social deviants on a show that features episode names reminiscent of a sideshow flyer, including “Double D-Saster,” “Lumpy Lady Lumps,” and “Welcome to Jurassic Schnoz.”19

Perhaps the popularity of the historical and contemporary sideshow demonstrates that humans are destined to find fascination in novelty. Spectators, including physicians and bioethicists, have always been enthralled by unusual medical cases and have even acquired knowledge from them. However, it is all too easy to perpetuate a narrative that reads a person only as his or her alleged condition. And ultimately, whether face-to-face with a patient during clinical rounds or broadcasting on television to the masses, it is often the physician who decides the answer to the patient’s pressing question, “Am I normal?”

References

- Phineas Taylor Barnum, The Life of P.T. Barnum: Written by Himself (New York: Redfield, 1855), 148-149.

- “The Joice Heth Exhibit: The Lost Museum.” American Social History Project/Center for Media and Learning at The Graduate Center, City University of New York, accessed April 4, 2019, https://lostmuseum.cuny.edu/archive/exhibit/heth.

- Rosemarie Garland Thomson, ed., Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body (New York and London: New York University Press, 1996).

- Michel Foucault, Abnormal: Lectures at the Collège de France 1974-1975, trans. Graham Burchell (London and New York: Verso, 2003), 63.

- Rosemarie Garland Thomson, “Introduction: From Wonder to Error – A Genealogy of Freak Discourse in Modernity,” in Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body, ed. Rosemarie Garland Thomson (New York and London: New York University Press, 1996), 10.

- Peter Osborne, “Merrick, Joseph Carey [called the Elephant Man] (1862–1890),” Dictionary of National Biography (2006), accessed April 6, 2019, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-37759.

- Sir Frederick Treves, The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences (London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne: Cassell and Company, Ltd, 1923), 3.

- Rosemarie Garland Thomson, ed., Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body (New York and London: New York University Press, 1996).

- Robert Bogdan, “The Social Construction of Freaks,” in Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body, ed. Rosemarie Garland Thomson (New York and London: New York University Press, 1996), 28.

- Ibid, 23-37.

- Nadja Durbach, “Conclusion: The Decline of the Freak Show,” in Spectacle of Deformity: Freak Shows and Modern British Culture, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 171-184.

- Robert Bogdan, “The Social Construction of Freaks,” in Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body, ed. Rosemarie Garland Thomson (New York and London: New York University Press, 1996), 23-37.

- “Woman’s Stomach Muscles Collapsed after Pregnancy – Embarrassing Bodies – Only Human,” YouTube video, 10:12, posted by “Only Human,” July 7, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z4R2jbFXlJQ&t=114s.

- “Labiaplasty – Lindsay’s Story,” YouTube video, 4:36, posted by “educationalcontent,” November 2, 2008, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7onyn-J4hnE.

- “‘Enlarged’ labia on ‘Embarrassing Bodies’,” The Student Room, accessed April 4, 2019, https://www.thestudentroom.co.uk/showthread.php?t=569452.

- “Dr. Now’s Best Moments-My 600-lb Life: Where Are They Now?,” YouTube video, 7:48, posted by “tlc uk,” July 1, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y2i7_2yfI2s.

- Julia Kristeva, An Essay on Abjection, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982).

- Joan Kroan, “What to Expect on This Season of Botched,” Allure, April 21, 2015, https://www.allure.com/story/botched-season-2.

- “Botched, Episode Guide,” IMDb, accessed April 6, 2019, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt3781836/episodes?ref_=tt_ov_epl.

CAMILLE KROLL is a first year Master’s student in Northwestern University’s Medical Humanities and Bioethics Program. She completed her undergraduate education at Macalester College, with a major in Biology and a minor in Hispanic Studies. Her current interests are the history of medicalization and its impact on society.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 11, Issue 3 – Summer 2019

Leave a Reply