Emily Boyle

Dublin, Ireland

It is difficult to think of Ophelia, one of Shakespeare’s most famous characters, without bringing to mind the famous depiction of her by John Everett Millais. In Hamlet, the sensitive and fragile Ophelia is driven mad by grief after her lover Hamlet rejects her and kills her father Polonius. After very poetically taking leave of her senses, Ophelia decks herself in “fantastic garlands” of wild flowers, wanders out of the castle to a nearby stream singing to herself, and as Gertrude describes it in the play:

When down the weedy trophies and herself

Fell in the weeping brook. Her clothes spread wide;

And, mermaid-like, awhile they bore her up:

But the unfortunate Ophelia soon sank and drowned.

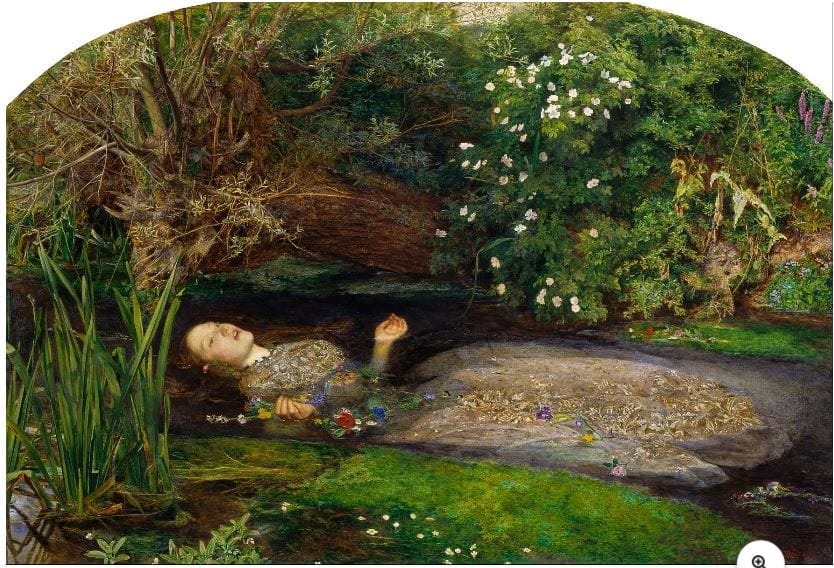

The painting by Millais captures the natural setting and the shape of Ophelia’s dress spread out just underneath the surface of the water before it starts to sink and drag her down (Fig 1). Perhaps the most striking part is the desolate expression on her face and her outstretched hands almost in supplication. So iconic is the pose that the image has been imitated many times.

To achieve such a realistic depiction, Millais spent many hours painting a model who posed for him in a bath to recreate the watery effect of the stream. His model Elizabeth Siddal, known as as Lizzie, became famous in her own right largely because of this painting, and led a shortened life filled with as much drama and tragedy as that of Ophelia.

Lizzie Siddal was born in 1829 in London, one of six children. Although her father ran his own cutlery business, he also spent much time and money pursuing a legal claim to a property, which he ultimately lost. Consequently the family was less well-off than expected.1 There is no record of Lizzie ever attending school, although she was able to read and write and loved poetry from a young age. Given their parents’ aspirations towards property ownership, Lizzie and her siblings had been instructed in manners and social niceties, which probably affected her bearing.1 By the age of twenty, she was tall, slightly androgynous, and described as being striking rather than beautiful1 with distinctive red hair like “dazzling copper.”2 These qualities helped her get her first job. She had been working in a milliner’s shop in London in 1850 when she was spotted by a friend of the artist William Deverell. At the time he was working on a large painting of Twelfth Night and needed a model to pose for Viola (who was disguised as a man).1 Lizzie’s striking looks were perfect for this role. He was very satisfied with the “stunner.” He was part of a circle of artists who came to be known as the pre-Raphelites and counted Ford Maddox Brown, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and John Everett Millais among their number. Rosetti had sat for the Jester in the same painting and was immediately taken with Deverell’s new model. Rossetti did not waste any time pursuing her and asked her to sit for him on her second day in Deverell’s studio. The two quickly began a relationship. While initially Lizzie posed for the other pre-Raphelites and became the muse and subject of many famous paintings, after 1852 she sat only for Rosetti. The two spent much time together at his lodgings.

In 1852 she posed as Ophelia. Famously, as Millais required her to pose in a bath for long periods of time, he used lamps to heat the water from below. However these blew out over hours and the water became icy cold. Lizzie lay uncomplaining in the water but became very unwell. She may well have had pneumonia as her family had to call a doctor. They threatened legal action against Millais, who ultimately did pay for the medical bills.3 She was almost certainly prescribed laudanum by her doctor at this stage and would be doomed to use this heavily over the years. This may have been the beginning of her years of ill health.

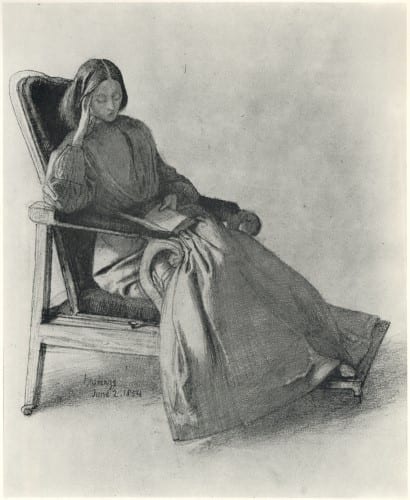

Rossetti and Lizzie went on to have a tumultuous, volatile relationship. He initially had an obsession with her and painted her many times, perhaps most famously as Beatrix. While certainly his muse, she was also a student to him. He encouraged and supported her own artistic tendencies and she began to draw and write poetry. He seemed to take delight in her drawings and showed them to his friends whenever they visited.2,4 He brought her drawings to the attention of John Rushkin, a well-known are critic who was so impressed that he offered her a stipend.5 An 1853 drawing by Rossetti (Fig 2) shows him posing for Lizzie who is leaning intently over her easel. However despite living together they did not have a formal engagement. He did not introduce her to his mother until 1855, was not faithful, and from 1854 embarked on the first of several affairs. This lack of stability in the relationship may have contributed to her subsequent anxiety and depression.

There are many references to her ill health in Rossetti’s letters from 1852 onwards and Lizzie looks increasingly unwell in later paintings—pale, fragile, and weak.2,6 The main symptoms he describes in the letters are wasting, weakness, and unspecified pain.

There were several possible explanations for her ailments amid uncertainty about the exact nature of her illness. For example it is frequently stated that she was suffering from tuberculosis (TB).6,7,8 This would explain her pale features and delicate appearance, both of which were typical for those with TB, and the chronic nature of her illness. Even her own friends and associates seemed to believe this. There was a sense at the time that TB was associated with artistic qualities, and Lizzie displayed some of these attributes in addition to beauty and fragility. Dante himself did not state to the contrary, perhaps seeing this as a more acceptable explanation for her ill health.6 She did eventually consult with Dr. Henry Acland, a clinical professor of medicine at Oxford who felt she was not consumptive and that her heath issues were more likely due to non-organic causes.9

Another explanation was that she was displaying some of the effects of laudanum over-use. Laudanum is a combination of an opioid with spices and alcohol, also known as tincture of opium. First described in 1655,10 it was prescribed freely in Victorian times for a wide variety of ailments and was widely available.11 It was a popular drug—it has been said that “Among medicines offered by Almighty God to relieve human suffering none is so universal and effective as opium.”12 Because of its widespread use many people became addicted and needed increasing doses to obtain the same effects.11 Famous laudanum users include Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Edgar Allen Poe, and Percy Shelley. Laudanum was often associated with artists, as its mind-altering effects were said to encourage artistic expression.13 However, it could be dangerous in overdose and was associated with more suicides than any other drug in Victorian times.11 Lizzie was known to use laudanum heavily.

Her symptoms, however, fit better with a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa. She ate very little and frequently felt weak. She once told Rossetti that “she had not eaten for a fortnight.”2 There are many references in Rossetti’s letters to her lack of appetite. An 1857 letter to Ford Maddox Brown describes her “never eating anything to speak of” and as late as 1861 in a letter to John J. Dalrymple he describes “an unfortunate lack of appetite.”2 Anorexia was not formally described until 1873 by Sir William Gull.14 He was one of the first to recognize the absence of an organic cause and described many of the now well-known features, including the fact that it frequently affects young females, and the common symptoms of fatigue, weight loss, and anorexia.15

Although Rossetti was obviously concerned about her health, this did not have the effect of stabilizing their relationship. He continued to have many affairs; they separated and only lived together again in 1860 when her family informed him how unwell she was and he rushed to her side.5 They married in May 1860, and although Lizzie became pregnant after their honeymoon, tragically their baby daughter was stillborn. Lizzie lapsed into a deep depression after this and died nine months later from an overdose of laudanum. A brief inquest ruled that she died “accidentally, causally and by misfortune”16 although it has been suggested that the overdose was not accidental.2,16 Her own words in the poem “Worn Out” seem sadly prophetic:

I can but give a sinking heart

And weary eyes of pain

A faded mouth that cannot smile

And may not laugh again

Even after her untimely death there were further dramatic events. In a grand gesture Rosetti had buried a notebook of unpublished poems in her coffin. In 1869 he had her coffin exhumed to retrieve them.16 Famously, although unrealistically as it was seven years since her burial, it was said at the time of exhumation that her looks were preserved and her hair retained its distinctive color and had continued to grow.16,17 Rossetti would go on to suffer depression, drug and alcohol addiction, and a mental breakdown in the years following her death. Lizzie’s final appearance on canvas is in the famous painting Beata Beatrix (Fig 4), which was only completed after her death and is often seen as a memorial to her.

While Lizzie Siddal has been immortalized in many paintings, she may be best known as the tragic Ophelia as depicted in the moment of her death, and indeed her own life and untimely death were no less tragic.

References

- Hawksley L. Lizzie Siddal: The Tragedy of a Pre-Raphaelite Supermodel. 2nd Ed, London, UK: Andre Deutch Ltd; 2013

- Shefer E. Deverell, Rossetti, Siddal, and “The Bird in the Cage”. The Art Bulletin 1985; 67(3):437-448. doi:10.2307/3050961

- http://www.shakessays.info/Essay%20on%20a%20shakespeare%20related%20piece%20of%20work%20-%20Ophelia%20by%20Millais.htm

- Holmes J. Rebels of art and science – the Pre-Raphelite Brotherhood. Nature 2018; 562: 490-491 doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-07110-9

- Bradley L. Elizabeth Siddal: Drawn into the Pre-Raphaelite Circle. Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 1992; 18(2): 137-187. doi:10.2307/4101558

- Byrne K. Tuberculosis and the Victorian Literary Imagination. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2011

- https://theweek.com/articles/692701/romance-tuberculosis

- http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O15042/elizabeth-siddal-drawing-rossetti-dante-gabriel/

- Doughty O, Wahl JR. EDS, Letters of Dante Gabriel Rosetti. Oxford: Clarendon, 1965-67

- Hamilton GR, Baskett TF – In the arms of Morpheus the development of morphine for postoperative pain relief. Can J Anaesth, 2000;47:367-374

- Berridge V, Edwards G. Opium and the People. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1981.

- Baraka A. Historical aspects of opium. Middle East J Anesthesiol, 2000;15:423-436

- De Quincey T, Milligan B. Confessions of an English opium eater. London, UK: Penguin Ltd 2004

- Silverman A, Gull WW. Limner of anorexia nervosa and myxoedema. An historical essay and encomium. Eat Weight Disord. 1997;2(3):111-6

- Gull WW. Anorexia nervosa (apepsia hysterica, anorexia hysterica) Trans Clin Soc London. 1873;7:22

- Accidental Death: Lizzie Siddal and the Poetics of the Coroner’s Inquest. Victorian Review, 40(2), 17-22. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/24877707

- https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/public/did-rossetti-really-need-to-exhume-his-wife/

EMILY BOYLE received her medical degree in 2004 from the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland. Having worked and trained in many hospitals around Ireland, she is now a Consultant Vascular Surgeon in Tallaght University Hospital in Dublin. She has always enjoyed art and became interested in the life of Elizabeth Siddal after reading about tuberculosis in the nineteenth century.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 11, Issue 3 – Summer 2019

Leave a Reply