Mildred Wilson

Detroit, MI, USA

Nineteenth Century African American

Landscape Artist

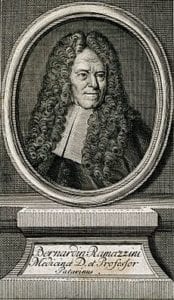

Lead poisoning (saturnism) has been present throughout history.1 Italian physician Bernardino Ramazzini is considered the first to have made the connection between paint and artists’ health. In his book De Morbis Artificum Diatriba published in 1700, he stated, “The many painters I have known, almost all I found unhealthy. . . . If we search for the cause of the cachectic and colorless appearance of the painters, as well as the melancholy feelings that they are so often victims of, we should look no further than the harmful nature of pigments.”2

Art lovers have often tried to interpret art pieces through the lens of the artist’s gender, race, or behavior, thereby limiting their understanding of the work. What art lovers have not realized is that many artists had also unwittingly embarked on a suicide journey, as lead slowly poisoned their bodies.

The biography of Robert Seldon Duncanson, a nineteenth-century landscape artist, is muddied with legends, typos, and suspect motives.3 However, it is worth noting that he was acknowledged by critics, patrons, and the public in the mid-nineteenth century as the “best landscape painter in the West.”4 This was an extraordinary honor, considering that Duncanson was an African American. But he, like Michelangelo and Caravaggio, suffered “painter’s colic.”5 Further, scientists assert that because he was an African American, lead poisoning had a greater effect on him than other racial groups.6

Duncanson was born in 1821 in Fayette, New York, to a poor family of free African American tradesmen. His paternal grandfather Charles had been a former slave from Virginia who moved there around 1790 with his son John. Charles was the illegitimate offspring of his master, but he had been permitted to learn a skilled trade and later to earn his release from bondage.7

In the last decade of the eighteenth-century white attitudes toward freedmen were increasingly hostile in the Upper South and the benefits of freedom were legislated away from free African Americans by Black Laws. They stood outside the direct governance of a master, but in the eyes of many whites their place in society had not been significantly altered. They were slaves without masters.8

Charles was skilled as a house painter and taught the trade to his son John. In 1828, Charles died. John and his wife Lucy had five sons and two daughters. Fayette was too small to support a growing number of skilled tradesmen, so he moved his family to Monroe, Michigan where he became a successful housepainter and carpenter. Robert was apprenticed in the family trade and initiated into mixing colors, preparing surfaces, and painting.9

In 1838, Duncanson and an associate, John Gamblin, formed a partnership in the business of painting and glazing. The partnership lasted a year. It is speculated that Robert’s ambition to become an artist rather than an artisan caused the dissolution of the business. Duncanson had taught himself the fine art of painting by diligently copying prints, painting portraits, and sketching from nature.10

In 1840, Duncanson moved to Cincinnati, Ohio. It was a free state, but it was pro-slavery in attitude.11 The Ohio Constitution denied blacks the right to vote and the Black Laws imposed further restrictions. Duncanson, cognizant of the problems, felt it was a place of opportunity because it was a major art center that liked to boast that it was the “Athens of the West.”12

Duncanson was befriended by a regional group of Cincinnati landscape painters, including T. Worthington Whittredge and William Louis Sonntag. These artists, like Duncanson, had begun their careers in the skilled trades as house, sign, and scenic painters. They exhibited their work at the Western Art Union and encouraged Duncanson to exhibit his work. They rejected prejudice and told him they would back him up.13

In 1842, three of Duncanson’s paintings were accepted, even though no blacks were permitted to see the exhibit. He was disappointed because his mother could not see his exhibited work. She, however, understood the ways of a southern town and said, “It isn’t that I haven’t seen the paintings. I know what they look like, and I can stand not seeing them there because I know they are there! That’s the important thing. They are there!”14 Duncanson did not win a prize, but his work made an impact, stirring up feelings of disbelief and praise among the visitors.

Following the War of 1812 America sought to establish a new identity. Thomas Cole and Asher Durand founded the Hudson River School style, which sought to portray the physical attributes of America and express an American spiritual, political, and social identity. Wittredge and Sonntag had been exposed to this style of aesthetics and Duncanson learned to appreciate the conventions of landscape painting from them.15 He went on several sketching trips to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. In 1848, Duncanson received a large commission to do a landscape of the first significant copper mine in the United States. It was titled Cliff Mine Lake Superior.16

Duncanson’s work as a landscape painter caught the eye of Nicholas Longworth, an abolitionist and one of the wealthiest men in the United States. He was also the primary arts patron in Cincinnati. In 1850 he commissioned Duncanson to decorate his home with monumental landscape murals. This was the largest project of the artist’s career, consisting of eight huge landscape decorations in trompe-l’oeil French rococo frames.17

Father of Occupational Medicine

In 1853, Duncanson accepted a commission from noted abolitionist and Episcopalian minister Reverend James Conover, to paint a scene from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s book Uncle Tom’s Cabin. He chose to illustrate a contemplative moment from Chapter 22. He titled the work Uncle Tom and Little Eva. He received a scathing review by a writer with the Cincinnati Daily Commercial who pointed to what he believed to be clumsy and ill-proportioned figures. The writer called the painting “An Uncle Tomitude.”18 Deeply shaken, Duncanson returned to landscape painting and never again strayed from that genre.

As a result of the sponsorship of Longworth, Duncanson studied the great artists in England, Scotland, and Italy.19 While he valued the experience, he preferred to remain close to home. He traveled between Cincinnati and Detroit to paint and emerged in the 1850s and 1860s as the principal landscape painter in the Ohio River Valley. He, along with James Pressley Ball, a daguerreotypist, formed the nucleus of a group of African American artists during the decade prior to the Civil War.20

In the early 1860s, Duncanson moved to Canada to escape the physical restraints and psychological trauma of the Civil War. He had painted what he called his “great picture,” Land of the Lotus Eaters, taken from the epic poem “The Lotus Eaters” by Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and exhibited it among the Canadians who accepted him into their cultural community without reservations about his skin color. He remained there several years and contributed to founding a national landscape painting school.21

For thirty years Duncanson ran the gauntlet, warding off the slings and arrows of well-meaning abolitionists, art critics, racists, and loved ones. He was particularly hurt by his son Reuben, who had accused him of passing for white in order to advance his social and economic stature. Reuben felt his father’s paintings should reflect concerns with slavery and other current African American problems.22 In a letter to his son in the 1870s, Duncanson wrote, “Mark what I say in black and white. I have no color on the brain. All I have on the brain is paint. I care not for color.”23

Although Ramazzini is considered the first to have made the connection between paint and artists’ health, it would take centuries for painters to switch to less harmful materials, even as medicine gradually clued into the bodily havoc wreaked by lead.24 Duncanson did not switch. In the 1860s, he developed a malady that increased in severity, resulting in periods of artistic inactivity. By 1870, his poor health prevented him from working regularly.25

No contemporary doctor diagnosed Duncanson’s illness, but modern medicine would classify the artist’s behavior as psychotic, characterized by a disorganized personality with an impaired perception of reality. He had worked for years as a house painter whose primary medium was the lead used to whitewash houses. Art historians speculate that his exposure during those years to massive quantities of lead white would have had a toxic effect that increased as he continued to grind his colors and prepare his grounds for canvases.26

In October 1872, Duncanson suffered a seizure in Detroit while hanging an exhibition. He was taken to the Michigan State Retreat where he died on December 21, 1872. Funeral services were held in Detroit and his body was taken to Historic Woodland Cemetery in Monroe, Michigan. For over a century there were only two tombstones in the family plot: one for his father John Dean and one for his sister Margaret.27

In 2018, a group of Detroit-area art patrons, spearheaded by Dora Kelley of Monroe, Michigan, took an interest in Duncanson and raised money to memorialize his resting place. After 147 years of resting in obscurity, in 2019 he will finally be honored with a tombstone.28

References

- Montes-Santiago Julio. The Lead-Poison Genius: Saturnism in Famous Artists Across Five Centuries, accessed March 28, 2019, http://www.ncbi.nim.nih.gov/pubmed/24041283.

- Khazan, Olga. How Important Is Lead Poisoning to Becoming a Legendary Artist, accessed March 28, 2019, http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2013/11.

- Kahn, Eve. M. Condeming Slavery With a Paintbrush. Accessed March 28, 2019, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/27/15arts/design/painter-robert-s-duncanson-and-jewelry-exhibitions.html.

- Ketner, Joseph D. The Emergence of the African American Artist, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri, 1994, pg. 1.

- Montes-Santiago, Julio, Op. Cit.

- Ketner, pg. 184.

- Ibid., pg. 12.

- Berlin, Ira. Slaves Without Masters, The New Press, New York City, New York, 2007, xxv.

- Ketner, pg. 12.

- Ibid., pgs. 12-14.

- Bearden, Romare and Henderson, Harry. Six Black Masters of American Art, Zenith Books, New York City, New York, 1972, pg. 21.

- Ketner, pg. 1.

- Beard and Henderson, pg. 26.

- Ibid., pg. 27.

- Ketner, pg. 5.

- Ibid., pg. 6.

- Ibid., pg. 50.

- Ibid., pgs. 47-48.

- Ibid., pg. 72.

- Ibid., pg. 2.

- Ibid., pg. 2.

- Ibid., pg. 94.

- Ibid., pg. 111.

- Khagan, Olga, Op. Cit.

- Ketner, pg. 176.

- Ibid., pgs. 183-184.

- Ibid., pg. 184.

- Hooper, Ryan Patrick. Pioneering Black Artist Robert S. Duncanson Will Finally Get Tombstone, accessed March 28, 2019, http://www.freep.com/story/entertainment/arts/2018/09/30/african-american-artist-duncanson-grave/1452886002.

MILDRED WILSON has a Masters of Teaching in Visual Art and a Doctorate in Curriculum Development and Administration. She is a former high school art teacher, elementary principal, and a deputy director/consumer advocate for the Michigan Legislative Service Bureau. She currently spends her time as a caregiver for her mother and writing fiction and nonfiction.

Highlighted in Frontispiece

Leave a Reply