Emily Nghiem

Detroit, Michigan, USA

|

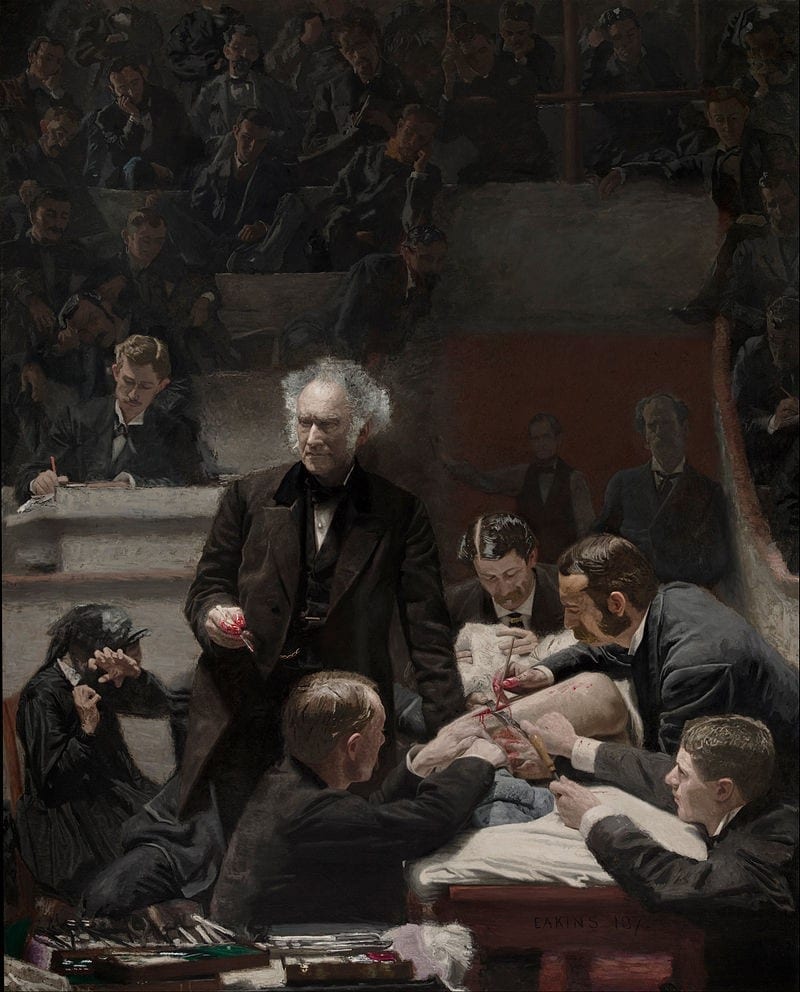

| The Gross Clinic by Thomas Eakins. 1875. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Wikimedia Commons Public Domain. |

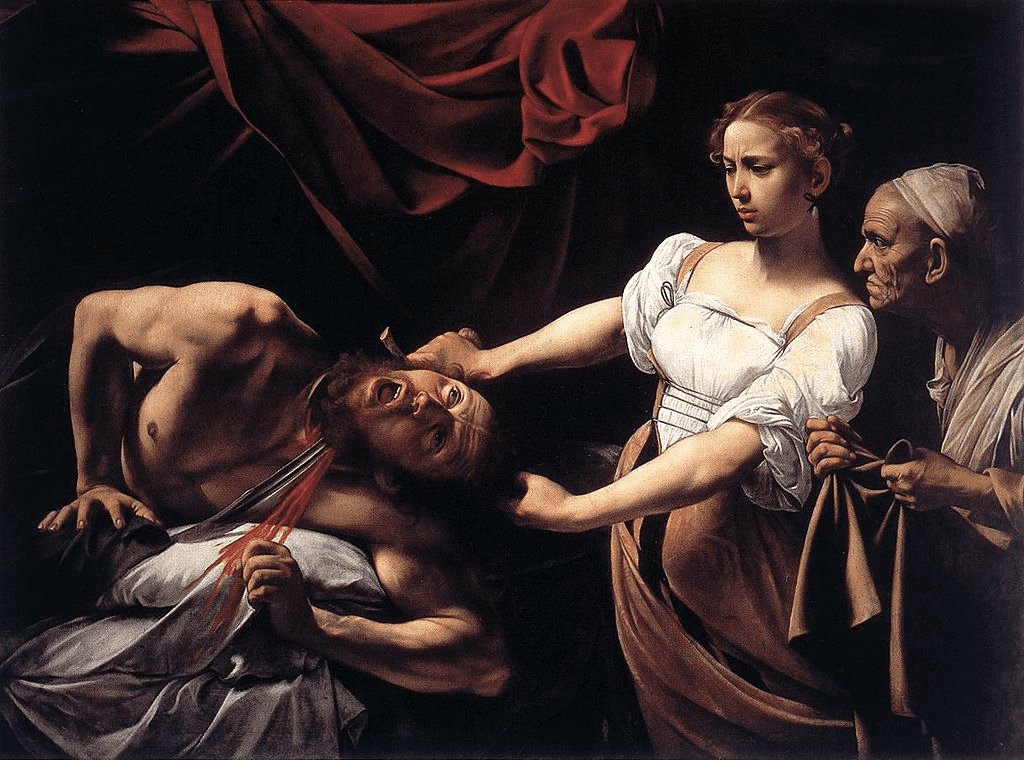

Art and medicine are not two things that seem to fall together naturally. When considering an example of medicine depicted in art, a reasonable and literal choice would be Thomas Eakins’ The Gross Clinic, where a team of doctors is performing live surgery before an intently fascinated audience. So many depictions of medicine in art show scenes of healing or surgery, mending the body back together. That is, after all, the core of the practice. But based on my experience with both art and medicine, the first image that jumps into my mind is Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio’s Judith Beheading Holofernes. In some ways it is the antithesis of healing, showing the dismemberment of the human body and a life being taken. However, in my mind, it is the perfect snapshot of my internal state on the day I first stepped foot into anatomy lab.

I first came across this painting by Caravaggio in an undergraduate art history class. Like many Italian paintings, the subject matter has religious roots. The widow Judith steps forward as an unlikely heroine when the men in her village prove too fearful to face their intimidating Assyrian enemy Holofernes. After praying to God for strength, she seduces the general, waits until he is inebriated, and beheads him, saving her people.1 Over the course of several classes we discussed the main attributes of the piece: the theatrical setting characteristic to Italian Baroque, the jarringly unrealistic stream of blood flying from Holofernes’ neck, and the impossible angle at which Judith holds her sword (having sawed at a human body myself, I can now confirm that she has nowhere near the necessary amount of leverage). I remember empathizing with Judith when we addressed the deeply furrowed brow that betrays her horror, mentally noting that I would make the exact same face if I ever had to cut into a human body. A few years later, after earning my degree in art history and being accepted into medical school, I thought of Caravaggio’s Judith as we unzipped the body bag on the first day of anatomy lab and felt my own brow start to furrow in horror.

|

| Judith Beheading Holofernes by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, c. 1598-99. Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Rome. Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain. |

Anatomy lab was only one of many worries on my mind as I began my journey to a career in medicine. Science had always been a passion of mine, but never my entire life. I entered college confident that I wanted to go to medical school, yet still decided on a major in art history because I knew I could never abandon my love for art. I proudly started medical school straight out of college and was immediately met with doubt that bordered on regret. I wondered if I had made a huge mistake, as I had barely finished enough science classes to carry me through the MCAT and to check off all the necessary boxes on my applications. Meanwhile I looked around and saw students in my class with double majors or master’s degrees in science. In a way I think it was this fear of inadequacy that drove me to pick up a scalpel in anatomy lab and start cutting. Every gut instinct of mine was drowned out by the fear of falling behind my classmates and so I became Caravaggio’s Judith—sword, furrowed brow, and all.

|

| Judith Beheading Holofernes by Artemisia Gentileschi, c. 1614-20. Uffizi Gallery, Florence. Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain. |

Thankfully the entire year was not driven purely by fear as I, along with the rest of my classmates, became accustomed to the sights and smells of our cadavers and grew increasingly fascinated with the mechanics of the human body. Viewing every lab as an opportunity to learn made the cutting feel second nature, more of a means to an end. Although I did not grasp it at first, I began to understand the reasons for our purposeful dissections. At one point in the year I stopped to think of another rendition of Judith Beheading Holofernes by Artemisia Gentileschi. The comparison between Gentileschi and Caravaggio’s interpretations of the same Old Testament scene is a staple in Italian Baroque art history classes. Gentileschi’s broad-shouldered Judith takes charge of the situation with a sure grip and steely brow—a stark contrast to Caravaggio’s willowy, reluctant heroine. Another detail that never escapes discussion is the trajectory of blood in Gentileschi’s piece. It is often hypothesized that the trajectory and resulting splatter take a much more realistic parabolic arc, as they were painted after Galileo’s proposal of the theory of projectile motion.2 In my undergraduate class I recall delighting over the application of science in art. Now, in medical school, I delighted over the realization that just maybe I was beginning to feel more like Gentileschi’s Judith.

A common conclusion in the Gentileschi vs. Caravaggio comparison is that Caravaggio painted a patronizing, misogynistic depiction of the Old Testament heroine whereas Gentileschi, a woman herself, painted an empowered Judith. While I cannot deny that entire argument, I see some truth in Caravaggio’s unsure, reluctant Judith and at times still experience those feelings while trying to navigate the rigors of medical school. The beauty of Judith’s story in the Old Testament is that it is wide open to interpretation. Narrated from an outside perspective, there is barely any mention of the heroine’s emotions apart from her prayer for strength.3 Readers are given the outcome of her actions and are then left to wonder what she felt, perhaps reflecting on their own emotions.

When I reflect back on my first year of medical school, I feel pride in overcoming my fear of anatomy lab, a small but significant personal victory amid a challenging transition. However, stronger than this is the relief I feel at vanquishing an even bigger fear—fear that I would lose my connection to art in committing myself to a future in medicine. With newfound confidence in my abilities and my many passions, each new challenge standing in my way will be met head on with a sure grip and steely brow. Still, I will always remind myself to think back to the days I timidly held a scalpel, cutting with a furrowed brow, as a testament to how far I have come and what drove me to strive for better.

References

- Reif, Stefan C., and Renate Egger-Wenzel, eds. Ancient Jewish Prayers and Emotions: Emotions Associated with Jewish Prayer in and around the Second Temple Period. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2015. pp. 181-190.

- Perciaccante, A., P. Charlier, A. Coralli, and R. Bianucci. “‘There Will Be Blood’. Differences in the Pictorial Representation of the Arterial Spurt of Blood in Caravaggio and Followers.” European Journal of Internal Medicine34 (October 6, 2016): E46-47. Accessed March 8, 2019. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2016.06.010.

- Reif and Egger-Wenzel. Ancient Jewish Prayers and Emotions. pp. 181-190.

EMILY NGHIEM is a second year medical student at Wayne State University School of Medicine in Detroit, Michigan. She grew up in Ann Arbor, Michigan and studied at Detroit Country Day High School before earning her bachelor’s degree in History of Art at the University of Michigan. She aims to continue highlighting the connection between art and medicine as she completes her MD.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 11, Issue 3 – Summer 2019

Leave a Reply