Lee Andrews

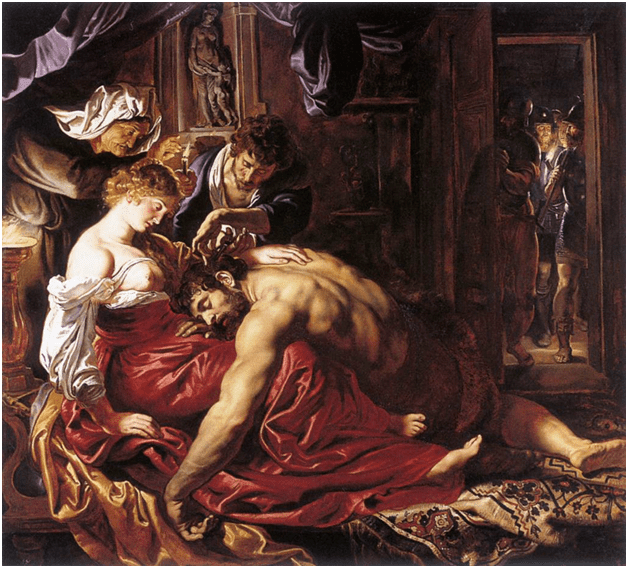

Peter Paul Rubens’ rendition of Samson and Delilah (1610) depicts Samson sleeping on Delilah’s lap as a Philistine cuts his hair, thereby removing the secret to his herculean strength. The artist who gave us the term “Rubenesque,” in which the words “plump” and “pleasing” describe the female form, had much to express about bodies in general. Following the compressed energy of Baroque composition, the couple dramatically sprawls across the entire frame, suggesting that the corporeal dominates this narrative. Samson’s hyperbolic muscles and Delilah’s exaggerated chest reduce the figures to a mere brute used for his strength and an object manipulated by the Philistines. Furthermore, Samson’s slumped position suggests unthinking intoxication, not dreaming repose. Yet wine has not made Samson drunk, but love: “for thy love is better than wine” (King James Version, Song of Solomon 1:2). A shadowy statue of Venus and Cupid in the corner of the painting serves as an ominous reminder of the cause of Samson’s plight.

Hebraic tradition warned Samson against women outside its cultural and religious boundaries, yet he crosses that line for Delilah’s love. Sleeping in her embrace therefore becomes a symbol for moral and military slackness, in which Samson tells his secret to the enemy because a woman gained control over him. In the painting, showing a sloppy Samson who has fallen asleep, we see a silent body. Yet in John Milton’s rendition of the narrative, Samson Agonistes, an articulate version of the hero is able to contemplate his bodily and moral weakness. Milton published the play in 1671 but possibly wrote it much earlier in his career, which would place the work closer to the Flemish artist’s rendition of the narrative (Parker 202). Both are Baroque in style, in which “the enormity of the temptation to be overcome, the gigantic effort required for the struggle” energizes the narrative (Roston 29). Agonistes translates to “struggle” or “action,” and amid these mythic battles, both moral and physical, the play gives language to the themes of appetite, consumption, bodies, and disseverance seen in the painting.

For Rubens, these themes gather at the juncture of Delilah’s breasts and the love as wine metaphor. Most paintings depict Delilah half-dressed, emphasizing her status as a deceitful, lecherous woman. Rubens’ painting does not deviate from this standard, and therefore does not necessarily confer a moral judgment on the individual. Lucas Cranach the Elder offers a notable exception in two renditions of the narrative, both of which present a chaste, covered Delilah with a serene expression (1530, 1537). Neither Rubens’ painting nor Milton’s rendition offers such a kind view of this woman.

The play articulates an alarming idea merely hinted at in the painting. Rubens gives his viewers a Samson seemingly sleeping off intoxication and the metaphor of love as wine; however, the proximity of Samson to Delilah’s breasts sheds a new light on his status as “a person separate to God,/ Design’d for great exploits” (SA line 31-32). Part of Samson’s special status requires dietary restriction, which further highlights the theme of moral overtones toward consumption. During Samson’s imprisonment, the Chorus says to him, “desire of wine and all delicious drinks/ Thou could’st repress, nor did the dancing Rubie/ Sparkling, out-pow’red, the flavor, or the smell,/ Or taste…Allure thee” (SA 541-546). Milton highlights the themes of the senses’ relationship to appetite and its repression. The image of a dancing ruby already lends itself to the feminine form, which foreshadows how Samson brings Delilah into the conversation. He replies, “what avail’d this temperance, not compleat/ Against another object more enticing?/ What boots it at one gate to make defence,/ And at another to let in the foe/ Effeminatly vanquish’t?” (SA lines 558-562). “Effeminately” references Delilah and therefore compares being drunk on wine to being drunk on love.

However, love as wine was not what Samson’s God intended him to drink. When Samson was God’s “nursling once and choice delight,/ His destin’d from the womb,” he “drank, from the clear milkie juice allaying/ Thirst” (SA lines 633-4, 550-1). That thirst called upon other sources for satisfaction, when he drank from Delilah’s “fair enchanted cup” (SA line 934). He substitutes God’s nurture and sustaining milk for Delilah’s intoxicating love. Samson could only eat certain foods, even more restricted than regular Hebraic law, specifically drinking only milky liquid. Combined with the visual in the painting, Delilah provides “malevolent nurture” (Trubowitz 190). The image of Delilah’s breasts, sexual or maternal, creates confusion between the lines of form and function in a perverse turn. The Samson narrative proclaims boundaries or prescriptions for right living that one cannot cross without incurring punishment.

When Samson does cross the boundary, we see the consequence of Delilah’s malevolent nurture. When maternal nurture and romantic love are confused, going against natural order, the result is castration, which appears for Samson in the form of having his hair cut and then losing all his strength. Samson relates the cause of his condition to his weakness, “swoll’n with pride [and] Softn’d with pleasure and voluptuous life,” at the point when Delilah cuts his hair (SA 532-4). In this relaxed moral state, Samson yields control of his language and Delilah takes the opportunity to relieve him of his “precious fleece” and strength (SA 538). Delilah figuratively castrates Samson, like a ram or “wether” (SA 538). As Samson “at length lay” in Delilah’s “lascivious lap,” he creates a thematic and alliterative chiasmus that verbally forms the trap into which Samson places his physical and moral worth, “head and hallow’d pledge,” tied by meaning and “h” alliteration (SA 535-6). Delilah’s “snare” transforms her into a monstrous woman, with whom any sexual union results in castration. Perhaps Milton here codes Delilah as a dangerous “other” in order to support a “biblical interdiction against exogamy, forbidden marriage with an outsider or other [which] supplied grounds for divorce that were not restricted to adultery” (Sauer 180). In any case, we see a firm line of justice set in place, warning against consuming foreign fare.

The theme of disseverance develops from the literal loss of hair and strength and figurative castration for Samson in the play. He suffers dissociation of self from body, noticeable when he cries, “My self, my Sepulcher, a moving Grave,/ Thou art become (O worst imprisonment!)/ The Dungeon of thy self” (SA 154-6). Here Milton physically separates “my” from “self” and distinguishes the body as an entirely separate entity. In Rubens’s painting, Samson is merely a sleeping body, reposing after being more of a body than a mind. We have no access to his dream world; however, his posture suggests sleeping off the intoxication of fulfilling a bodily appetite, just as wine slakes thirst. In the play, Milton endows Samson with a reflective mind that contemplates his body as a prison. His fragmented figure suggests that the body on its own is incomplete and therefore broken in some way. Milton shows Samson broken down both physically and emotionally, just as Delilah was disassembled and reduced from whole personhood into exaggerated and vilified female sexuality.

Rubens depicts the height of the narrative in his painting; however, the play embodies a search for meaning for this sorrowful situation. Samson in the play wrestles, in a Miltonic twist on a Baroque, epic struggle, “to understand a life that has undergone a radical metamorphosis” (Kilgour 303). He is coming to terms with his mind and body being split and thinking about the desires and actions that brought him there. After following an appetite that leads him to cross a boundary, he is literally and metaphorically cut off, blinded, emasculated, and imprisoned. The idea of separation and being driven out evokes the theme of abjection, a highly important idea in Israelite law. Samson’s identity as God’s nursling, remaining inside the group, depended on what he consumed according to the physical requirement of drinking only the milky liquid rather than wine. When he consumed something outside the boundaries, Samson received the literal punishment of abjection, “the state of being cast off.” In fact, “the end of Samson Agonistes provides a vivid reminder that “not all that is exigent can be redeemed or remembered” (Song 147). Therefore, the message might be caution towards what you eat or consume, take in and see. Although Israelite eating requirements very much deal with literal consequences for consumption, Samson Agonistes highlights the figurative process of feeling an appetite, seeing something that would fulfill it, consuming, digesting, and being nourished, malevolently or beneficially by it.

The process of consumption highlights something critical about art for us. If identity is linked to consumption, we become what we take in, through our eyes and ears, as well. The idea of nurture shows how being fed these things, for example, Samson consuming Delilah’s love as wine, changes his identity. He no longer enjoys status as an appointed nursling of God and suffers painful separation of mind and body because of it. The cycle of need, desire or appetite, consumption, metabolism, and digestion shows a strong system of cause and effect. Consumption changes us, just as appetite shapes action, by impacting the body like intoxication and its effect on judgment and perception.

The message of these visual and textual narratives tells of desire driving action. Samson’s wine of choice may be love, but anything has the power to drive appetites and impact identity. For instance, we take in art and literature and a multitude of other things, and for better or for worse, are transformed by it.

References

- Kilgour, Maggie. “Reading Samson Agonistes.” Milton and the Metamorphosis of Ovid. Oxford University Press, 2012, pp. 298-318. Print.

- Milton, John. Samson Agonistes: The Complete Poetry and Essential Prose of John Milton. Ed. William Kerrigan, John Rumrich and Stephen M. Fallon. New York: The Modern Library, 2007. 707-761. Print.

- William Riley Parker; The date of “Samson Agonistes”: A postscript, Notes and Queries, Volume CCIII, Issue may, 1 May 1958, Pages 201–202, https://doiorg.ezproxy.princeton.edu/10.1093/nq/CCIII.may.201

- Roston, Murray. “Milton’s Herculean Samson.” Changing Perspectives in Literature and the Visual Arts, 1650-1820. Princeton University Press, 1990, pp. 13–40. Print.

- Rubens, Peter Paul. Samson and Delilah. 1609-10. The Tate Gallery, London, UK. https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/peter-paul-rubens-samson-and-delilah

- Song, Eric. “Gemelle Liber: Milton’s 1671 Archive.” Dominion Undeserved. Cornell University Press, 2012, pp. 111-151. Print.

- Trubowitz, Rachel. “ “I was his nursling once”: Internationalism and “nurture holy” in Samson Agonistes.” Nation and Nurture in Seventeenth-Century English Literature, Oxford University Press, 2012, pp. 188- 229. Print.

LEE ANDREWS studied English literature with an interest in art history as an undergraduate. She carries that passion for humanities into her graduate studies of behavioral and mental health and eventually seeks to pursue a doctorate in the field.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 11, Issue 1– Winter 2019

Leave a Reply