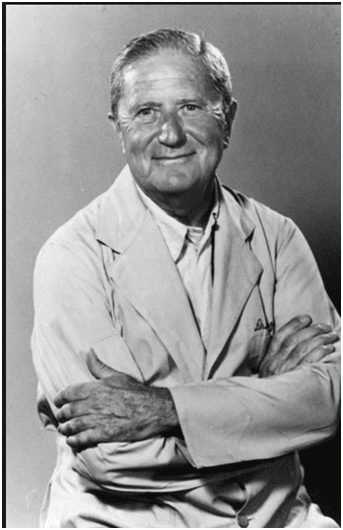

For more than thirty years, in an era less politically correct than ours, Dr. Loyal Davis reigned supreme as chief of surgery at the Northwestern University medical school in Chicago. He retired in 1963, but stories about him persisted as lively subjects of conversation and amusement, to be told with relish at meetings and dinner parties, not all verifiable and some perhaps apocryphal.

It is said that he kept an enemy list in his office. He was tyrant in the operating room, terrifying his staff, insisting on having his personal area to scrub, his own gown, and his own gloves. He viewed his interns as nothing more than specks on the horizon. Some remember having to be in the hospital at all hours, not allowed to leave until they obtained permission on the phone to do so from him, from his wife if he was unavailable, or by default from his housekeeper.

He was a good writer, author of the biography of JB Murphy, the flamboyant surgeon of Chicago’s earlier days, and also his own autobiography, called A Surgical Odyssey. Born in Galesburg, Illinois, son of a railway engineer, he attended Knox College and graduated from Northwestern University medical school in 1918 at the top of his class. He obtained a doctorate for research in neuroanatomy, survived the hardships of an internship at Cook County Hospital, spent time in general practice in Galesburg, but then left for Chicago to become a surgeon. He had an early marriage to Miss Pearl McElroy, which took place without their parents’ attendance, in what he calls in his book an “illogical, unnecessary, inexcusable evasion of decent manners.” She moved to Chicago with him but is not mentioned again in his book. Later he married again, an actress, and became the stepfather of Nancy Reagan, the future wife of the United States’ fortieth president.

After completing his training in neurosurgery, Dr. Davis settled in Chicago, carried out research in neuroanatomy, and at the age of thirty-six became chairman of surgery at Northwestern University. As a highly respected and innovative neurosurgeon, he received immense recognition, honors, and accolades. He was president of the American College of Surgeons, long-term editor of Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics, founding member of the American Board of Surgery, recipient of the Legion of Merit for work as a consultant during World War II, and honorary Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of England and Edinburgh.

He was greatly influenced during his formative years by Harvey Cushing, his great but not lovable mentor. Cushing was at the time the most capable neurosurgeon in America. His fame was great, his surgical skill incontestable. Abrupt in his dealings with staff and agents, especially when discussing fees and planning, Cushing appeared to his patients (especially the wealthy ones) sweet and compassionate, sitting down at their bedside on rounds and holding their hands while taking the history or explaining what he was planning to do. But with his young trainees, his fellows or residents, he was curt, distant, and sarcastic in the presence of others, often addressing them only indirectly through his aides, sometimes ignoring them for weeks at a time. When Dr. Davis came to him he curtly told him to make himself at home, then left him wandering around the wards for weeks without any guidance, not ever speaking to him or even acknowledging his presence, then all of a sudden calling him in and asking who gave him permission to examine his private patients. When having his residents to dinner at his house, Cushing’s aides would be peremptorily issued an invitation to present themselves at his house at seven pm. After dinner he would take them to the library, tell them to look at his good books on Vesalius, then leave to go work on his oeuvre on the life of Sir William Osler, and not see them again during that evening.

When Loyal Davis returned from Boston to Chicago he had already acquired some of Harvey Cushing’s personality traits. Both men appear to have believed that the successful surgeon had to be a tyrant and severe disciplinarian, that strict observation to detail could only be achieved through severity, fear, and distancing oneself from one’s staff. Possibly such attributes and personality traits go hand-in-hand with the genetic makeup needed to make a truly great surgeon, including perhaps some inborn hostility to those who will someday will take their place, such as seen in the animal kingdom or in Saturn devouring his own children.

Loyal Davis retired in 1963 after having taught surgery to thirty classes of undergraduate medical students and to fifty graduate students or residents in surgery and neurological surgery. He did not take kindly to the turbulent changes of the seventies, reflecting that his father’s generation would not have approved of the young men’s long hair, scraggly beards, T-shirts, sandals, and ragged blue jeans, believing that his children and grandchildren had “no right to ask him to tolerate to tolerate their excessive displays of disapproval of accepted and well-established norms of social and professional behavior.” “My hair stands on end,” he wrote, “when I overhear a newly graduated intern arrogantly tell an experienced and excellent internist that in the neophyte’s opinion, based on his experience, that internist was treating the patient incorrectly.” He likewise disliked the structural changes beginning to occur in American medicine at that time, the “indecisive, appeasing, pusillanimous actions of administrators of universities, colleges, medical schools, and hospitals.” But at the end of a long and successful career he became calmer and non-emotional, reflecting upon the actions taken in his youth “not with regret but with an appreciation of how they could have been better.”

Recollections of a medical student, class of 1964:

When doctors of my generation who attended Northwestern University Medical School are gathered in conversation, the name of Dr. Loyal Davis becomes a topic of discussion. Some of the well-told tales are legendary, perhaps apocryphal, often humorous, seldom flattering, and reflect the spectrum of fear and terror he inspired.

The summer before I entered medical school in 1960, I obtained a student research opportunity to work in the offices of the department of surgery, an attractive series of offices with windows that also housed the offices of Dr. Davis and his secretary. On one occasion, a fellow medical student and I obtained permission to observe Dr. Davis in surgery across the street at Passavant Memorial Hospital. I do not think he really welcomed our presence in the operating room and made us stand in a corner of the room at a safe distance from the operating table. It was a perceptibly tense environment and at one point when my colleague attempted to lend a hand by adjusting a light that was not to the surgeons liking, he garnered Dr. Davis’s wrath for daring to touch a device about whose function he did not know the first thing.

When medical school formally started in late August, it was the custom that the entire class was required to attend a meeting on Saturday morning with Dr. Davis. It was emphasized that 100% attendance, no exceptions, was expected. Our class consisted of 109 students, nine of whom were women. Dr. Davis began the meeting by stating that he really did not care for women in medicine, that if they were considering a career in surgery they could forget it, and that he certainly did not want them parading their femininity around his operating room. No one in the class protested his remarks, certainly none of my fellow gentlemen classmates would have considered stepping up.

The remainder of my recollection of the meeting was that he had every member of the class stand up and tell him where they were from and who their parents were as well as their profession. I think he seemed to be looking for students whose parents were physicians and to find out where they practiced. One member of our class was absent, and his name was singled out by name for what sounded like a summary execution. One useful advice piece he gave us in that meeting that I never forgot. He told us never to undertake a procedure without the proper equipment. He ended the meeting by admonishing the class that if anyone favored socialized medicine they should withdraw immediately.

At the end of the sophomore year, before starting our third-year clinical rotation in surgery, the entire class was required to schedule an appointment with Dr. Davis at his office. It was not a warm or friendly meeting. Dr. Davis sat behind his desk at a mechanical typewriter (much as doctors today peer into their laptops while talking to their patients) and asked a few questions relating to the students plans for their medical career. The answers elicited no response of interest or encouragement, and the interview was abruptly terminated. In retrospect, I imagine that depending on one’s interest in surgery, the purpose of the interview was to determine which of the third-year surgical rotations one would be assigned. As I was interested in internal medicine, I was far away from the downtown medical school campus.

As part of our clinical training, the entire class did a rotation for two weeks at a maternity center delivering babies. It was not unusual for the team delivering a baby in a patient’s home to be asked to provide a name on the birth certificate that was completed at the time of each delivery. Many babies received the name “Loyal Davis.” It was my understanding that when word of this practice reached the higher levels of the university, it was frowned upon and forbidden.

Comments by a former intern:

I think it would be worth mentioning that a personality like his would not survive in medicine today. Supposedly he occasionally slapped nurses in the operating room when they displeased him. This may be apocryphal. One of my medical school roommates was observing him operate when the scrub nurse dropped a retractor on the floor. She was so terrified of him that rather than tell Dr. Davis there would be a delay while she re-sterilized the instrument, she waited until she thought no one was looking and scooped the instrument off the floor and replaced it on the Mayo stand.

The anticipation of the obligatory interview with Dr. Davis before beginning the junior year surgery rotation was terrifying. He would ask each student what he planned to do in his career. Certain responses would result in immediate expulsion from his office. The classic unacceptable response was that you wished “to do general practice with a little surgery on the side.” There were other less well known unacceptable career plans, so you had to be on your guard. As I had not taken any clinical clerkships at time of my interview, I told him that I was keeping my options open. He seemed to find this reasonable position rather spineless.

Dr. Davis’ wife Edith is a subject worthy of an article of her own. She swore like a sailor, but moved in the highest strata of Chicago society. Her daughter Nancy, as everyone knows, married Ronald Reagan and eventually became the First Lady of the United States. She was rumored to be the daughter of Edward G. Robinson.

Some years after his retirement, I saw Dr. Davis as a patient on several occasions. Before his first visit, I was terrified, but he proved to be a pleasant and cooperative patient.

Comments by another former intern:

My recollection of the freshman class meeting with Dr. Davis is similar to the other. It was mandatory. Dr. Davis showed us (class of 1963) a bust of his hands executed by an artist and which he was going to gift to some friends. He then spoke of playing bridge with Hollywood personalities such as Walter Houston and others. Most of us had no idea who these people were or their relationship to our medical training. I do remember him saying that a doctor could talk anyone into lying down on the operating table and that it was our responsibility to be qualified to carry out the appropriate procedure.

I think the maternity center experience was of more social than obstetrical value although the delivery of babies by junior medical students without much backup was sometimes exciting. The well-loved stories of many babies being named Loyal are interesting but I don’t know of any corroborating witnesses.

I do not believe that all interns were required to be at the hospital at all times. One exception was the emergency room assignment. Each intern was required to take emergency room (ER) duty for one month. This was Dr. Davis’ idea. The intern saw every applicant to the emergency room and was the primary evaluator and treatment person, whether heart attack, stroke, asthma, bone fracture, laceration, etc. The intern was not allowed to leave the hospital during that month, not even to get a haircut. During the period the intern would see 700 or 800 patients and in retrospect it was good experience, although sleep deprivation-induced delirium tended to set in about week three.

When I returned from military service and was in surgical residency I did spend four months working in the neurosurgery department. I also heard the story about an incident when Dr. Davis was operating and his regular scrub nurse accidently dropped one of his favorite instruments on the floor. Knowing he would need it soon, she simply reached down, retrieved it from the floor, and replaced it on the scrub table. This may speak of the fear or intimidation Dr. Davis could instill.

Dr. Davis was always kind to me when later I was on the medical staff, giving me books which he edited when they were related to my field or to review. I think his major contribution to medicine was his forceful push for certification of surgeons to ensure competence and his push to eliminate fee-splitting, a truly corrupt practice, as well as his efforts to enhance the American College of Surgeons. In the time now when doctors have become to some extent gray, faceless widgets in an increasingly impersonal medical environment, it is pleasant to reflect on the personalities of the past.

I heard many stories about Dr. Davis. He was a brilliant surgeon; an author; a tyrant; he kept an enemies list. His former residents recollected that they were on call every night and had to call for his permission to leave the hospital; if he happened to be away the permission had to be granted by the wife or failing that, by the housekeeper. I also heard that many residents, resentful of his tyranny, whenever they had to go out into the community to deliver babies would name them Loyal. It was to be expected that many young men grew up bearing that name.

Dr. Davis was an outspoken conservative on both professional and political matters. He was known throughout the medical world for his practice and teaching of surgery. Davis’s specialty widely honored him for contributions to neurosurgery; as an author and editor; as an honorary fellow of many distinguished societies; for his involvement in medical political controversies about fee splitting; for his contributions to the training of surgeons; and as a colonel in World War II who made improvements in the treatment of injuries. He retired in 1963 and died in Scottsdale, Arizona in 1982 at the age of eighty-six.

Leave a Reply