Emily Moore

Ames, Iowa, United States

|

The USS Red Rover was commissioned on December 26, 1862, by the Union as the first US Navy hospital ship. It had been built in 1859 as a commercial use wooden side-wheel river steamer and purchased in 1861 by the Confederate States of America. In 1862 it was bombarded and captured on the Mississippi River by a Union gunboat and later refurbished as a floating summer hospital, this at a time when medical care was very limited.1

At the beginning of the war the Army used steamers and transports as makeshift hospitals to carry casualties upriver. Sanitation and hygiene were very poor, and by the time the war ended, “more men had died from diseases as malaria, measles, small pox, cholera, typhoid fever, typhus and dysentery than died of gunshot wounds.”2 Most patients hoped to just make it to port for better facilities. An agent of the Governor of Indiana said after the Battle of Shiloh, “From what I have already seen I think the sick need better attention.”3 Sanitation was of great concern, and the need for a hospital ship such as the USS Red Rover was great.

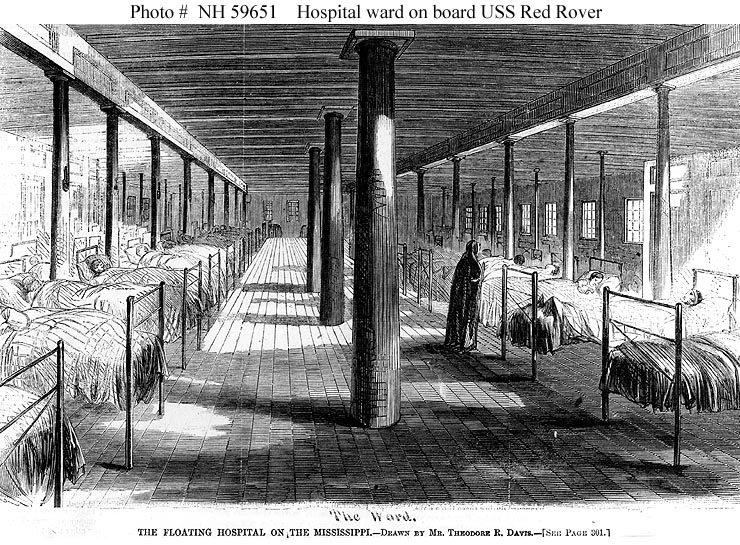

With the financial assistance of the Western Sanitary Commission and civilian efforts, the concept of a fully equipped and efficient medical ship became reality. In the rebuilding of the USS Red Rover an operating room was installed, also a galley with separate kitchen facilities for patients and staff, an icebox of 300 ton capacity, an open cabin aft for better air circulation, gauze blinds placed over windows to reduce cinder and smoke, and a steam boiler in the laundry room. There was even an elevator for transporting patients between decks.2,4

On board there were stores for three months and medical supplies sufficient for 200 persons.2 The ship was also armed with one thirty-two pounder gun,2,4 and had a crew of twelve officers and thirty-five men. Some thirty other persons worked in the medical department, four of those being Sisters of the Holy Cross.1

The significance of the USS Red Rover as the first hospital ship cannot be underestimated, but the untold story of other firsts, the “Sisters” and the “Contrabands”, are equally important in the story of the healing of the nation. On October 28, 1861, the Sisters of the Holy Cross were sent to St. Louis, Mo., Cairo and Mound City, Illinois to tend to the sick and wounded.

We were not prepared as nurses but our hearts made our hands willing and our sympathy ready, and so with God’s help, we did much towards alleviating the dreadful suffering.5

According to Naval records, Sister M. Veronica, Sister M. Adela and Sister M. Calesta transferred on Christmas Eve, December 24, 1862, from the Army Hospital at Mound City for service on the USS Red Rover.1 They were joined by Sister M. John on February 9, 1863, and later by others, all becoming the first female nurses on a US Navy hospital ship at a time when there were no nursing schools in America, nurses in military hospitals having no formal training, and election was based primarily on their being at least thirty years old, demure, and with a moral reputation.3 In Sis. Calesta’s account of battle and serving, she states:

Mother M. Angela and I slept on a table on some clothes which had been sent to be washed. After the battle of Fort Donelson, February 16, 1862 … many had been neglected on the field; and frozen fingers, ears and feet were the result. Sometimes men were brought in with worms actually crawling in their wounds. After one battle there were 700 sick and only four sisters to wait on them. It was a heart-rending to see the poor men holding out their hands to the Sisters to attract attention, for many were not able to speak. At another time the smallpox raged among the soldiers and we had charge of the pest house.5

Mother Angela continues,

General Strong and his staff visited today. It was a great display and contrasted the pomp of war on one side with its misery and horror on the other as they passed…wards filled with the wounded sick and dying.5

The USS Red Rover made several trips on the Mississippi River with sick and wounded. On one trip Mother Angela and Sister Veronica were on the mail boat when it was attacked and a shot passed directly through Sister Veronica’s veil.5 By their commitment, the Sisters of the Holy Cross and other women became the predecessors of the U.S. Navy Nurse Corps.6

During the Civil War twenty percent of the US Navy’s total enlisted force were black sailors, primarily escaped slaves, referred to by the Union as “contrabands”7 and were identified as confiscated property that could have been used by the Confederacy in the war. After the passing of the Confiscation Act of 1861 and in defiance of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, the Union determined there was no legal obligation to return these contrabands to slavery.8

Black sailors constituted a significant segment of naval manpower and nearly doubled the number of black soldiers serving in the U.S. Army. They did manual labor or worked in general assistance, damage control units, and small arms crews, but their maritime skills were strategically important on the Mississippi River and in the work of the Mississippi Squadron. At the combined army and navy assault on Vicksburg, commanders took great advantage of the knowledge and experience of the black sailors.7 As the hospital ship assigned to the Mississippi Squadron, the USS Red Rover sailed with them during actions.9 Thus, contrabands, both male and female, played an important role during the war, particularly on the USS Red Rover.

Women contrabands served in various capacities. Unrecognized as nurses, they were often identified as cooks, laundress, and chambermaids even though they performed nursing duties and cared for the sick.10 There were two female contraband nurses, Alice Kennedy and Sarah Kinno, when the USS Red Rover was commissioned, December 26, 1862 and they were joined later by Ellen Campbell, Betsy Young, Dennis Downs, and Ann Bradford Stokes.1 Working under the direction of the Sisters of the Holy Cross, these black women contrabands were chosen because their midwifery skills had made them accustomed to blood.9 They were enlisted as “first class boys” and paid as such. (First class boys were young men under seventeen years old performing general sailor duties.11)

Ann Bradford Stokes came aboard the USS Red Rover January 25, 18632 as a contraband, unable to read and write. She was taught skills by the Sisters of the Holy Cross and remained on active duty until October 1864. She married another contraband, Gilbert Stokes, also in service on the USS Red Rover, and they later moved to Illinois. After his death she applied for disability pension on her husband’s service, at first unsuccessfully, but with her literary skills reapplied in 1890, basing her claim on her eighteen months service on the USS Red Rover. She proved her disability, so that born in slavery, she was the first woman to receive a pension for military service in the United States.12

As a “first” the USS Red Rover was the platform that launched efforts to heal a nation divided by war, killing, disease, and racial hatred. It was the first US Naval Hospital Ship, financed in part by the Western Sanitary Commission, a forerunner to the Red Cross.14 It was the first time that American women served as nurses in active military duty, the service of the Sisters of the Holy Cross being a forerunner to the US Navy Nurse Corps. Another first was the recognition of Ann Bradford Stokes by awarding her a pension for service to her country. Furthemore, the enlistment of male and female “Contrabands” whose service was exemplary, transcended race and color at a time when race and color were at the center of the conflict.

Speaking at the Western Sanitation Fair in March 1864, President Abraham Lincoln recognized and honored the women, white and black, who pioneered social change in America:

If all that has been said by orators and poets since the creation of the world in praise of women applied to the women of America, it would not do them justice for their conduct during this war.”13

In this effort the unique journey of the USS Red Rover served as a healing spirit for a divided nation.

References

- US Navy Department, “History of U. S. Navy Hospital Ship Red Rover”, 1962. https://archive.org/details/HISTORYOFU.S.NAVYHOSPITALSHIPREDROVER Accessed January 10, 2015

- Dike, William L., U.S.S. Red Rover: Civil War Hospital Ship. Baltimore: Publish America, 2004, pp. 5,14, 22, 56, 60

- Seigel, Peggy Brase, She Went to War: Indiana Nurses in the Civil War. Indiana Magazine of History, Vol. 86, March 1990: 11-12

- 290 Foundation, U.S.S. Red Rover, https://sites.google.com/site/290foundation/history/u-s-s-red-rover Accessed December 31,2014

- Sis M. Eleanore. On the King’s Highway, A History of the Sisters of the Holy Cross of St. Mary of the Immaculate Conception. New York: D. Appleton and Co., pp. 197-295

- Red Rover – The U.S. Navy’s First Hospital Ship. Dennis M. Davidson. http://archive.org/details/RedRoverTheU.S.NavysFirstHospitalShip Accessed January 10, 2015

- Reidy, Joseph P. Black Men in Navy Blue During the Civil War, Part 1 and 2. Prologue, Fall 2001 33(3). http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2001/fall/black-sailors-2.html . Accessed December 31, 2014

- Rogers, C.J., Seidule, T. and Watson, S. U.S. Military Academy, The West Point History of the Civil War. NY: Simon and Schuster, 2014

- Southernmost Illinois History. http://www.southernmostillinoishistory.net Accessed January 10, 2015

- U.S. Colored Troops During the Civil War. Transcript, March 16,2013 http://www.c-span.org/video?311639-2/us-colored-troops-civil-war

- Civil War Virtual Museum, Trans-Mississippi Theater. http://civilwarvirtualmuseum.org Accessed January 10, 2015

- Maggie MacLeon, Civil War Nurses on Hospital Ships, African American Women on the Red Rover, Civil War Women Blog, November 14, 2014 http://civilwarwomenblog.com/civil-war-nurses-on-hospital-ships/ Accessed January 24, 2015

- Sanitary Commission Fair in Washington. The History Channel website; http://www.history.com /this-day-in-history/sanitary-commission-fair-in-washington Accessed January 31, 2015 15. US Sanitary Commission. http://www.ourstory.info/1/USSC.html Accessed January 30, 2015

EMILY L. MOORE, EdD, is Professor Emerita, College of Human Sciences, School of Education, Iowa State University. She served as Associate Dean for Academic and Faculty Affairs; Chair and Professor, Department of Health Studies; Director, Master in Health Administration (MHA)-Global program in the College of Health Professions, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston.

Spring 2015 | Sections | Hospitals of Note

Leave a Reply