Natalia Vieyra

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States

Etching and drypoint, plate: 9 5/16 x 14 inches (23.75 x 35.6 cm)

Sheet: 12 5/8 x 17 5/8 inches (32.1 x 44.8 cm)

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Purchased with the SmithKline Beckman Corporation Fund, 1980

The etchings of Paul-Albert Besnard constitute a gruesome assemblage of nineteenth-century social ills—graphic depictions of the hard lives of women plagued by sickness, suicides, prostitution, infanticide, and poverty. Amid this collection of unfortunate modern imagery, an unusual etching featuring two fashionable Parisiennes stands out (Fig. 1). Who are these elegant women, enjoying the ephemeral pleasures of café life? As the title illuminates, they are morphinomanes—the notorious female morphine addicts of fin-de-siècle France. By the turn of the century, the proliferation of drug culture and morphine abuse had reached seemingly epidemic proportions, leading one novelist to declare, “In Paris alone, there are more than three hundred thousand scum who shoot up morphine, drink ether, swallow hashish, smoke opium.”1 Viewed as both source and symptom of a society in decline, the topic of morphine abuse permeated nearly all aspects of French cultural production in the final decades of the nineteenth century.

Despite the prevalence of morphine addiction across a demographic spectrum, artists nearly always visualized morphine addicts as young women indulging in a novel and distinctly modern vice.2 The figure of the morphinomane infiltrated French popular culture—her presence was noticed everywhere, from newspapers and medical publications to pulp literature and the minor arts, even making occasional forays into the Salon. However, the most recognizable representations of the morphinomane are not found in the academic disciplines of painting and sculpture, but rather within the medium of printmaking. This essay considers two unique prints, Paul-Albert Besnard’s etching, Morphinomanes ou Le Plumet (1887) and Eugène Grasset’s lithograph, Morphinomaniac (1897). Within this study, overlapping themes of drug abuse, sartorial indulgence, and sexual experimentation will be examined in relation to artistic depictions of the morphinomane in fin-de-siècle France.

In 1805 the young German chemist Friedrich Sertürner isolated pure alkaloid crystals from the opium poppy, a scientific breakthrough that would have a tremendous impact on modern medicine. Unaware of the momentousness of his discovery, Sertürner allegedly tested the crystals on himself, subsequently naming his compound after Morpheus, the Greek god of sleep and dreams.3 However, the medical applications of morphine remained limited until the mid-nineteenth century, when the invention of the hypodermic needle dramatically increased the addictive potential of the drug.4 The central Parisian pharmacy, for example, used just over a quarter of a kilogram of morphine in 1855; this increased to more than ten kilograms in 1875 and seven hundred and fifty kilograms by the 1890s.5

This explosion of morphine administration and abuse coincided with the humiliating defeat of the French army in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 and subsequent anxieties about the loss of health, strength, and virility in French society. First raised as question of nationalism in discussions at the Academy of Medicine in 1867, a general theory of degeneration provided an answer to the problem of France’s declining population in the latter half of the century.6 By the 1880s and ‘90s, the model of degeneration identified a vast number of interconnected social ills, including physiological diseases, sexual deviancies, and criminal behaviors, as sources of cultural decline. Above all, pleasure-seeking behaviors such as drug addiction and sexual promiscuity were disparaged for their degenerative potential.

As the dangers of morphine addiction became evident to the French public, fears about its abuse were enmeshed in the discourse of degeneration. In particular, drug use amongst women presented a serious national concern. At its most basic, morphine appeared to interfere with the primary civic duty of the French woman—to produce and nurture a new generation of healthy young men. Accordingly, artistic representations of morphine addicts emphasized the moral bankruptcy of the drug user and her inability to fulfill her feminine role. Envisioned as a dysfunctional individual “shamelessly seeking a sensation of pleasure,”7 the figure of the morphinomane provided a site for France’s crisis of degeneration to crystallize.

In the visual arts, printmakers like Paul-Albert Besnard (French, 1849–1934) and Eugène Grasset (Swiss French, 1845–1917) also participated in this discourse of degeneration, using a multilayered play of associations that enmeshed their morphinomanes in a network of interrelated pathologies. With his etching, Morphinomanes ou Le Plumet, Besnard envisioned a modish pair of morphine addicts indulging in their clandestine vice. This engaging composition features two elegantly dressed women enjoying a moment of leisure, possibly in a Parisian café or salon. Their fashionable attire alludes to morphine’s acceptance by the bourgeoisie as a novel and distinctly modern pleasure—one that Laurent Tailhade once described as a “sin of luxe.”8 Satirically termed the narcotic “à la mode,”9 by Jules Claretie, morphine addiction was so common amongst the upper classes that elegant hypodermic needles and bejeweled velvet-lined cases became fashionable accoutrements.

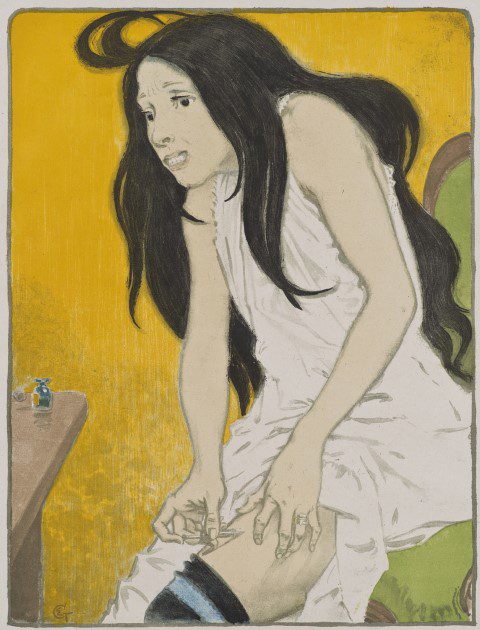

Eugène Grasset, Morphinomaniac, 1897

Color lithograph, Image: 16 1/14 x 12 5/16 inches (41.4 x 31.3 cm)

Sheet: 22 7/16 x 16 3/4 inches (57 x 42.5 cm).

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Purchased with the SmithKline Beckman Corporation Fund, 1983

Though Besnard’s title informs us of the predilection of these elegant women, the composition otherwise misses the typical accessories of addiction—the morphine vial, needle, and case are absent. Nevertheless, several elements allude to the sensuous pleasures enjoyed by these fashionably attired morphinomanes. As the pair relaxes, a swirling cloud of smoke recalls the languid atmosphere of an Oriental opium den. The fine crystal decanter in the foreground suggests the influence of an unknown and possibly illicit substance. Besnard’s application of drypoint creates a feathery blurring effect that suggests altered consciousness—as the smoke envelops the two figures their forms become fluid and indeterminate.

While the dark-haired figure on the left pointedly engages the spectator with her gaze, the figure on the right is preoccupied with an item in the spindly hand of her companion—a small feather. Its central position in the composition, as well as its allusion to the sensation of touch, indicates that the feather was perhaps meant as a suggestive stand-in for the morphine addict’s needle. These elements, the smoke, the decanter, and the feather, coalesce to form a representation of morphinomania that emphasizes the pursuit of sensuous pleasure, mirroring contemporaneous literary representations that described the physical sensations of the morphine high in titillating detail. Using evocative and multivalent imagery, Besnard’s Morphinomanes aligns feminine indulgence, the ephemeral pleasures of fashion, and synesthetic pursuits with the degenerative vice of morphine.

Published a decade later in 1897, Eugène Grasset’s Morphinomaniac (Fig. 2) offers a sharp stylistic contrast to Besnard’s fashionable demimondaines, using the intense colors and bold lines of the lithographic medium to create an atmosphere of tension and anxiety. In his disquieting image, Grasset envisioned the total physical and moral degradation of the morphine addict. Too disturbing for public display, Grasset’s print would have been examined only occasionally in the privacy of the owner’s cabinet de travail, safe from the detrimental effects of light and the prying eyes of the family. Compared to Besnard’s etching, which situates the morphinomane as participant in a decadent, albeit morally questionable pastime, Grasset’s lithograph presents the viewer with a shocking representation of abject degeneracy and sexual mania. The scene occurs in a confined interior space, defined by garish yellow walls and a chair upholstered in absinthe green. The cropped picture plane, influenced by Japanese wood block prints, adds to the sensation of claustrophobia. Nothing about this room suggests affluence—the furniture is simple and the texture in the yellow wallpaper gives the impression of mottled grime. Using these compositional elements, Grasset cultivates an atmosphere of palpable dysphoria.

As in Besnard’s Morphinomanes, the intrusion into a private interior composition indicates that the spectator has stumbled on an illicit secret. In a gesture loaded with autoerotic suggestion, Grasset’s morphinomane lifts her simple white shift and plunges the syringe into her exposed thigh, revealing her navy blue-striped stocking for a hint of fin-de-siècle naughtiness. As her hands and face contort in agony, her voluptuous, raven tresses cascade around her shoulders. Despite her gaunt, tortured visage, her thigh remains shapely and full, impressing the composition with a morbid sensualism. Unlike Besnard’s etching, whose subjects are imagined in the midst of a euphoric, drug-induced ecstasy, Grasset depicts the moment of tension just prior to intoxication. By selecting this moment, Grasset creates an atmosphere charged with erotic insinuation, as his morphinomane becomes an object of morbid fascination and repulsion.

Like Besnard’s Morphinomanes, Grasset’s Morphinomaniac can be considered in relation to French anxieties about societal decay. However, Besnard’s etching associates the morphine addict with the frivolous, sartorial indulgence of the Parisienne, whereas the autoerotic intimations of Grasset’s lithograph engage with another “social ill”— the solitary vice of “self-abuse.” Another facet in the model of degeneration, the nineteenth-century discourse surrounding masturbation bears a striking resemblance to that of morphinomania. This “contagious vice”10 was viewed not simply as a moral concern, but also as an addictive behavior that could lead to anemia, malnutrition, muscle and nerve damage, and mental exhaustion.11 Tapping into the language of degeneration, Grasset created a loaded image that would have simultaneously allured and repulsed French viewers. His morphinomane is unquestionably one of morphine’s prisoners, reduced to a state of grotesque dependency in her pursuit of sensuous pleasures.

As France entered the twentieth century, morphine decreased in popularity, as did artistic representations of the morphine addict. The invention of aspirin provided doctors with a safer painkiller, and morphine’s narcotic popularity was eclipsed by that of heroin. In many instances, the portrayal of addicts shifted away from the plastic arts to the new medium of cinema. Nevertheless, the prints of Besnard and Grasset provide a unique and indispensable opportunity to study anxieties surrounding pleasure and societal decay in fin-de-siècle France.

Notes

- Victorien du Saussay, La morphine: vices et passions des morphinomanes (Paris: Albert Méricant, 1906), 171.

- Statistics about morphine abuse in the late nineteenth century deviate wildly and are drawn from small population samples, making it difficult to assert concrete conclusions regarding user demographics. However, cases of addiction were recorded amongst both men and women of varying occupations and social classes. Additionally, it is worth noting that both male and female morphinomanes appear in French literature. However, Laura Spagnoli has argued that overall, literary representations female morphine addicts outnumber their male counterparts. In the visual arts, morphinomanes are nearly always represented as young women. For an in depth investigation of morphinomania in French literature of the fin de siècle and the Belle Epoque, see Laura Spagnoli, “Under the Influence: Literature, Drugs, and Modernity in France (1870–1914)” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2002).

- Barbara Hodgson, In the Arms of Morpheus: The Tragic History of Laudanum, Morphine, and Patent Medicines (New York: Firefly Books (US.) Inc., 2001), 79.

- The subcutaneous use of morphine began as early as the 1830s. Systems of injection advanced rapidly over the next twenty years, culminating in the perfection of the instrument in the 1850s by Charles Pravaz in France, Alexander Wood in England, and others. For a detailed chronology of the development of the hypodermic needle, see Richard Davenport-Hines, The Pursuit of Oblivion: A Global History of Narcotics (London, New York: Norton, 2002), 100–101.

- Howard Padwa, Social Poison: The Culture and Politics of Opiate Control in Britain and France, 1821–1926 (Baltimore: JHU Press, 2003), 67.

- Sharon Hirsh, “Codes of Consumption,” in In Sickness and in Health: Disease as Metaphor in Art and Popular Wisdom, ed.Laurinda S. Dixon (Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press, 2004), 154.

- Laurent Tailhaide, La “Noire Idol,” 8.

- Ibid.

- Jules Claretie, La vie à Paris:1880–1910 (Paris: G. Charpentier et E. Fasquelle, 1895).

- Nicholas Francis Cooke, quoted in Bram Dijkstra, Idols of Perversity, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), 74.

- Bram Dijkstra, Idols of Perversity, 64–82.

is a designer and art historian residing in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She received her BFA from the University of the Arts in Graphic Design with a minor in the History of Visual Art and is currently finishing her PhD in Art History at Temple University. Her research considers themes of health, medicine, and representation in nineteenth-century visual culture.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Summer 2015 – Volume 7, Issue 3

Leave a Reply