Barend Florijn

Ad Kaptein

The Netherlands

|

| Photography by thekirbster |

Introduction

The Dutch Euthanasia Act took effect in the Netherlands in 2002. Since then the official euthanasia number of patients with a mental disorder has risen from 13 in 2011 to 42 patients in 2013.1 This Act regulates the ending of one’s life by a physician at the request of an unbearably suffering patient. It defines euthanasia as death resulting from administering lethal drugs by a physician with the intention to end a patient’s life, at the patient’s explicit request.2,3 The following criteria are listed in this act: (1) there is a voluntary and well-considered request from the patient to end his life, (2) the patient is suffering unbearably without prospect of improvement, (3) the patient is informed about his situation and prospect, (4) there are no reasonable alternatives to relieve suffering, (5) euthanasia is performed with due medical care and attention, and (6) an independent physician must be consulted by the treating physician to evaluate criteria 1-5.4 However, the nature of ‘suffering’ [criterion 2] (i.e. physical or psychosocial) is not specified in the Dutch act.5

In 2009, the Dutch Association of Psychiatry published new guidelines for euthanasia request for mentally ill patients.6 An earlier version only partially encapsulated the clinical complexities and ethical dilemmas surrounding end-of-life decisions in patients with mental illnesses. Only general statements were made about the importance of interpreting the euthanasia request as a cry for help, and psychiatrists were warned to be particularly wary of requests from patients with personality disorders.4 The 2009 version offers a more detailed approach for physicians by specifically highlighting the complexity of assessing the decision-making capacity of the person in the presence of chronic mental illness.6 A study conducted in 1996 among 673 Dutch psychiatrists, showed that 205 of 552 respondents had received at least one explicit and persistent euthanasia request, of whom twelve complied.7 Most cases were of patients who had both a mental disorder and a serious physical illness that was unbearable or hopeless, and for which previous treatment had failed. One of the most frequent reasons, among psychiatrists, for refusing an euthanasia request was doubt that suffering was actually unbearable.7 In 2004 the same authors showed when the patient’s euthanasia request was refused, psychiatrists judged that the request was not well considered or that the patient had a treatable mental disorder.8 This raised the question whether the euthanasia request criteria can be fulfilled in mentally-ill (e.g., depressed) patients.

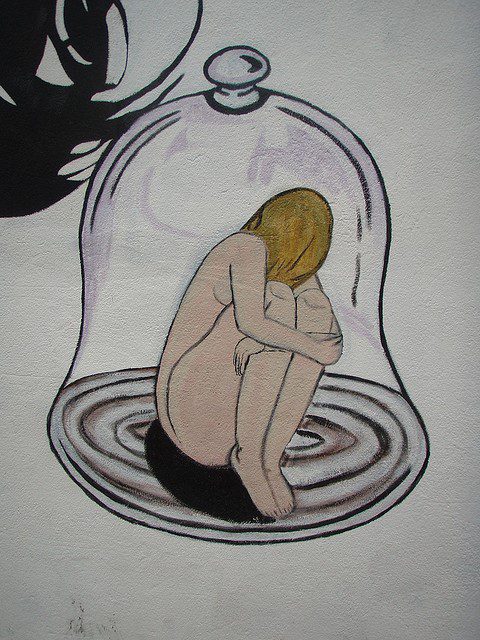

In The Bell Jar,9 Sylvia Plath sets forth the experience of protagonist Esther Greenwood, who has finished an editor-internship in New York. The 1950 American society obstructs Greenwood in becoming the ideal of a high-minded young woman. Living underneath a bell jar is a metaphor for a feeling of self-alienation: “To the person in the bell jar, blank and stopped as a dead baby, the world itself is the bad dream.”9 And, “(…) wherever I sat – on the deck of a ship or at a street café in Paris or Bangkok – I would be sitting under the same glass bell jar, stewing in my own sour air.”9

Computational software has been used to capture textual patterns in The Bell Jar. It revealed the following features of the protagonist’s life perception: disconnection from others, i.e. diminished awareness of other people, and persistent and inexplicable feelings of incapacity or impotence.10 These textual patterns show Sylvia Plath’s depression prose is honest in the way she perceives her depression as a multidimensional suffering with physical, mental and social aspects. These multidimensional aspects of depression can make suffering unbearable, impairing quality of life and happiness in general. Therefore, in this paper we attempt to illustrate that three of the Dutch euthanasia criteria can be met in the case of the depressed patient, making the euthanasia a reasonable option to relieve suffering. In case of Esther Greenwood and her Bell Jar narration, we show that psychological suffering can be unbearable, that she is informed about her situation, and there are no reasonable alternatives to relieve her suffering.

Methods

On the basis of selected quotes from The Bell Jar we aim to illustrate that the novel is a clear and unambiguous rendition of depression. In regards to the case of Esther Greenwood, the depressed protagonist from The Bell Jar, we studied if the previously mentioned criteria 2-44 from the Dutch Euthanasia act could be fulfilled and if a sustained euthanasia request could be a reasonable option to consider. Criteria 1 and criteria 5-6 will not be discussed. Within The Bell Jar there is no voluntary and well-considered euthanasia request from Greenwood and therefore no euthanasia is performed.

Results

Criteria 2-4 from the Dutch Euthanasia Act are: (2) the patient is suffering unbearably without the prospect of improvement, (3) the patient is informed about his situation and prospect, (4) there are no reasonable alternatives to relieve suffering.4

Criterion 2: “the patient is suffering unbearably”

Esther Greenwood perceives actuality very gloomy. For instance, when she ventilates the burden of socialising and self-awareness she exclaims: “My drink was wet and depressing. Each time I took another sip it tasted more and more like dead water.”9 “I felt myself shrinking to a small black dot against all those red and white rugs and that pine-paneling. I felt like a hole in the ground.”9

Her general dark experience of life lasts through the seasons: “The countryside already deep under old falls of snow, turned us a bleaker shoulder, and as the fir trees crowded down from the grey hills to the road edge, so darkly green they looked black, I grew gloomier and gloomier.”9 And, “(…) the motherly breath of the suburbs enfolded me. A summer calm laid its soothing hand over everything, like death.”9 After a writing course proposal is turned down, Esther Greenwood expresses her feelings as follows: “All through June the writing course had stretched before me like a bright, safe bridge over the dull gulf of the summer. Now I saw it totter and dissolve, and a body in a white blouse and green skirt plummet into the gap. … I felt it was very important not to be recognized.”9 She is also filled with disgust when considering future life prospects of girls her age when she mentions, “I looked round me at all the rows of rapt little heads with the same silver glow on them at the front and the same black shadow on them at the back, and they looked like nothing more or less than a lot of stupid moon-brains. I felt in terrible danger of puking.”9

Criteria 3 and 4: “the patient is informed about her situation and prospect”

After her fifth suicide attempt, Esther Greenwood finds herself in the consulting room of psychiatrist Dr. Gordon: “I was still wearing Betsy’s white blouse and dirndl skirt. They drooped a bit now, as I hadn’t washed them in my three weeks at home. The sweaty cotton gave off a sour but friendly smell. I hadn’t washed my hair for three weeks, either. I hadn’t slept for seven nights.”9 Dr. Gordon is unable to help Esther Greenwood and he does not inform her about her situation: “I had imagined a kind, ugly, intuitive man looking up and saying ‘Ah!’ in an encouraging way, as if he could see something I couldn’t and then I would find words to tell him how I was so scared, as if I were being stuffed farther and farther into a black, airless sack with no way out.”9 Instead of this, Dr. Gordon doesn’t communicate the state of Greenwoods situation at all: “He only said: ‘I think I would like to speak to your mother. Do you mind?”9

Dr. Gordon gives Greenwood shock treatments: “Dr. Gordon was fitting two metal plates on either side of my head. He buckled them into place with a strap that dented my forehead, and gave me a wire to bite. I shut my eyes. There was a brief silence, like an indrawn breath. Then something bent down and took hold of me and shook me like the end of the world. Whee-ee-ee-ee-ee, it shrilled, through an air crackling with blue light, and with each flash a great jolt drubbed me till I thought my bones would break and the sap fly out of me like a split plant. I wondered what terrible thing it was that I had done.”9

After the shock treatment that Dr. Gordon gives have failed, Esther Greenwood will have shock treatments again, but given by Dr. Nolan. First Greenwood doesn’t know that, but this new physician’s way of communicating is far more understanding than Dr. Gordon’s way: “Tell me about Doctor Gordon,’ Doctor Nolan said suddenly. ‘Did you like him?’ I gave Dr. Nolan a wary look. I thought the doctors must all be in it together, and that somewhere in this hospital, in a hidden corner, there reposed a machine exactly like Dr. Gordon’s, ready to jolt me out of my skin. ‘No,’ I said. ‘I didn’t like him at all.’ ‘That’s interesting. Why?’ ‘I didn’t like what he did to me.’ ‘Did to you?’ I told Dr. Nolan about the machine, and the blue flashes, and the jolting and the noise. While I was telling her she went very still. ‘That was a mistake,’ she said then. ‘It’s not supposed to be like that.’ I stared at her. ‘If it’s done properly,’ Dr. Nolan said, ‘it’s like going to sleep.’ Then Esther Greenwood says: ‘If anyone does that to me again I’ll kill myself.’9

Shock treatment will happen again and Dr. Nolan is able to communicate this sensitively: “Doctor Nolan put her arm around me and hugged me like a mother. ‘You said you’d tell me!’ I shouted at her through the disheveled blanket. ‘But I am telling you,’ Doctor Nolan said. ‘I’ve come especially early to tell you, and I’m taking you over myself.”9

Criteria 2 and 4: “there are no reasonable alternatives to relieve suffering”

When Esther Greenwood’s state of depression deteriorates, her suffering makes her determined to end life. This raises the question whether treatment has been successful at all, considering the tragic and detailed descriptions of her five suicide attempts in The Bell Jar. By cutting her wrists: “It would take two motions. One wrist then the other wrist. But when it came right down to it, the skin of my wrist looked so white and defenceless that I couldn’t do it.”9 Two times by drowning herself: “I waited, as if the sea could make my decision for me.”9 And “The water pressed in on my eardrums and on my heart. I dived, and dived again, and each time popped up like a cork.”9By hanging herself: “But each time I would get the cord so tight I could feel a rushing in my ears and a flush of blood in my face my hands would weaken and let go, and I would be all right again.”9 By hiding herself away in a basement to take a drug overdose: “It took me a good while to heft my body into the gap, but at last, after many tries, I managed it, and crouched at the mouth of the darkness, like a troll. I unscrewed the bottle of pills and started taking them swiftly, between gulps of water, one by one by one.”9

Dr. Gordon gives Esther Greenwood shock treatments, which don’t help: When Dr. Gordon asks Greenwood how she feels after her shock treatment: “How do you feel? ‘All right.’ But I didn’t. I felt terrible.”9

At the end of the novel Esther Greenwood is unsure whether shock treatment has been successful. “How did I know that someday – at college, in Europe, somewhere, anywhere – the bell jar, with its stifling distortions, wouldn’t descend again?”9 And, “I had hoped, at my departure, I would feel sure and knowledgeable about everything that lay ahead – after all, I had been ‘analysed’. Instead, all I could see were question marks.”9

Discussion

Esther Greenwood shows that the suffering of depressed patients can be unbearable to themselves. Her general way of looking at life is dark and she is unable to sleep for seven nights in a row. Ultimately, death may seem inevitable, as shown by five suicide attempts.

Criteria 3 and 4 from the euthanasia act are also nicely illustrated in this novel. First Esther Greenwood is poorly informed about her situation by Dr. Gordon, but later, she is perfectly informed by Dr. Nolan about future treatment plans. However, it is unknown whether this shock treatment has been successful for Esther Greenwood. She has been given it twice, but at the end of the novel Esther is still unsure about life ahead. After this shock treatment, no feasible alternative exists for such a severe depression like Esther Greenwood is suffering from. This raises the question of whether this form of suffering can meet the euthanasia suffering criteria.

Research has shown that depression can be perceived as a severe multidimensional suffering that affects physical, mental, social and spiritual aspects.11 Suffering is exacerbated by a depressed mood and by identification of one’s self as being depressed.12 Within The Bell Jar, Greenwood only once identifies herself as being depressed: “A fine drizzle started drifting down from the grey sky, and I grew very depressed.9 The entire narration however, reveals that Esther Greenwood is constantly accompanied by a depressed mood: “I saw the years of my life spaced along a road in the form of telephone poles, threaded together by wires. I counted one, two, three … nineteen telephone poles, and then the wires dangled into space, and try as I would, I couldn’t see a single pole beyond the nineteenth.”9Such suffering can make daily living intolerable. When living is intolerable, quality of life is impaired drastically forcing the depressed patient towards suicide, as is shown by The Bell Jar narration. In such cases, when suffering is indeed unbearable, euthanasia as an alternative to suicide can be far more satisfying to both patient and physician.13

The Dutch euthanasia criteria are difficult to assess because Dutch general practitioners, medical specialists, and nursing home physicians frequently report problems in evaluating the patient’s subjective perspective from the Euthanasia act criteria.14 This is related to evaluating whether or not suffering was unbearable and whether or not the patient’s request was voluntary and well considered.14,15 As demonstrated in a study on patients who explicitly requested euthanasia, but whose request was not granted, patients appear to put more emphasis on psychosocial suffering while physicians refer more often to physical suffering.16 In the case of Esther Greenwood, she does not reflect on her suffering. No expression of illness belief is given in the text. But the above results show that her view of life is gloomy and dark. Her behavior on the other hand, shows she is perfectly aware that death is a better option compared to living. To choose to end one’s own life, entails denying that life is preferable to death.17 Greenwood attempts to end her life five times. With this, she denies that life is preferable to death. This raises the question of whether life is good for her at all. Greenwood shows this preference with suicide attempts and her doubts about whether a happy future can be possible.

The Bell Jar is an elegant example in the field of literature and medicine. This narration can help physicians18 in valuing the honesty of the patient perspective, when having to evaluate the criteria as described in the Euthanasia Act, specifically in the case of a mentally ill patient. They can use this literary work of art to train themselves in assessing the Euthanasia Act criteria. This literary narration by Sylvia Plath shows that these criteria can be assessed in case of the depressed patient, making the euthanasia request a reasonable treatment option to consider.

Conclusion

Physicians face a judgment difficulty when evaluating euthanasia requests by depressed patients. However, with The Bell Jar’s honesty, it can help physicians to asses a depressed patient’s intention in order to fulfill the Dutch Euthanasia act criteria.19

References

- Schippers E. (Dutch Minister of Health, Welfare and Sport). Antwoorden op kamervragen over euthanasie bij mensen met een psychiatrische aandoening. In: Letter to The House of Representatives ed. The Hague; 2014.

- van der Heide A, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Rurup ML, et al. End-of-life practices in the Netherlands under the Euthanasia Act. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;356(19):1957-1965.

- Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Penning C, de Jong-Krul GJ, van Delden JJ, van der Heide A. Trends in end-of-life practices before and after the enactment of the euthanasia law in the Netherlands from 1990 to 2010: a repeated cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2012;380(9845):908-915.

- Pols H, Oak S. Physician-assisted dying and psychiatry: recent developments in The Netherlands. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2013;36(5-6):506-514.

- Naudts K, Ducatelle C, Kovacs J, Laurens K, van den Eynde F, van Heeringen C. Euthanasia: the role of the psychiatrist. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;188:405-409.

- Tholen AJ, Huisman J, Legemaate J, Nolen WA, Polak F, Scherders MJWT. Guidelines for physician-assisted suicide in case of the mentally-ill patient. In: Dutch Association of Psychiatry. Utrecht: De Tijdstroom; 2009:77.

- Groenewoud JH, van der Maas PJ, van der Wal G, et al. Physician-assisted death in psychiatric practice in the Netherlands. New England Journal of Medicine.1997;336(25):1795-1801.

- Groenewoud JH, Van Der Heide A, Tholen AJ, et al. Psychiatric consultation with regard to requests for euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2004;26(4):323-330.

- Plath S. The Bell Jar. London: Faber and Faber Limited; 1966.

- Hunt D, Carter R. Seeing through The Bell Jar: investigating linguistic patterns of psychological disorder. The Journal of Medical Humanities. 2012;33(1):27-39.

- Hedelin B, Strandmark M. The meaning of depression from the life-world perspective of elderly women. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2001;22(4):401-420.

- Kuwabara SA, Van Voorhees BW, Gollan JK, Alexander GC. A qualitative exploration of depression in emerging adulthood: disorder, development, and social context. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2007;29(4):317-324.

- Poma SZ, Vicentini S, Siviero F, et al. The Opinions of GP’s Patients About Suicide, Assisted Suicide, Euthanasia, and Suicide Prevention: An Italian Survey.Suicide & life-threatening Behavior. 2014;Epub ahead of print.

- Buiting HM, Gevers JK, Rietjens JA, et al. Dutch criteria of due care for physician-assisted dying in medical practice: a physician perspective. Journal of Medical Ethics. 2008;34(9):e12.

- Dees MK, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Dekkers WJ, Elwyn G, Vissers KC, van Weel C. Perspectives of decision-making in requests for euthanasia: a qualitative research among patients, relatives and treating physicians in the Netherlands. Palliative Medicine. 2013;27(1):27-37.

- Pasman HR, Rurup ML, Willems DL, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD. Concept of unbearable suffering in context of ungranted requests for euthanasia: qualitative interviews with patients and physicians. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2009;339:b4362.

- Frati P, Gulino M, Mancarella P, Cecchi R, Ferracuti S. Assisted suicide in the care of mentally ill patients: the Lucio Magri’s case. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine. 2014;21:26-30.

- Brody H. Defining the medical humanities: three conceptions and three narratives. The Journal of Medical Humanities. 2011;32(1):1-7.

- Marcoux I, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Jansen-van der Weide MC, van der Wal G. Withdrawing an explicit request for euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide: a retrospective study on the influence of mental health status and other patient characteristics. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35(9):1265-1274.

BAREND W. FLORIJN, MD, is currently a PhD student at the Department of Internal Medicine at the Leiden University Medical Center. Together with Ad A. Kaptein he has published before about Literature & Medicine in the American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine.

AD A. KAPTEIN, PhD, is a Professor of Medical Psychology at the Leiden University Medical Center. He teaches about living with chronic illness. His research focuses on illness perceptions, treatment beliefs, self-management and quality of life, in particular in persons with a chronic somatic illness. He was Editor-in-Chief of Psychology and Health, and President of the European Health Psychology Society (EHPS).

Spring 2015 | Sections | Psychiatry & Psychology

Leave a Reply