Renato Alarcón

Lima, Perú

|

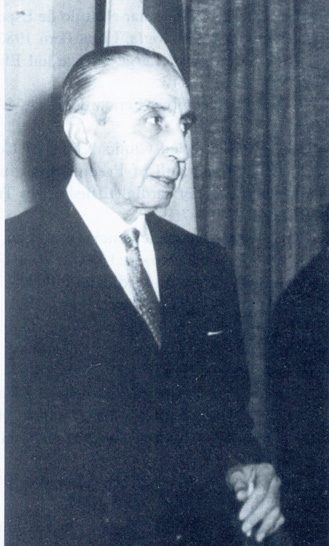

| Honorio Delgado (1892–1969) |

A sad fact in the history of medicine has been the benign neglect dealt to psychiatry by the rest of the profession. This has been even more painful within psychiatry itself, as its predominantly European and North American quarters practically ignored contributions from Africa, Asia, and Latin America. That is why the presence and impact of Honorio Delgado (1892–1969), his recognition by luminaries of world psychiatry, and his contributions to scientific knowledge, philosophical debates, and an authentic humanism constituted an unusual phenomenon at a point in history when globalization was sheer utopia. Even now an analysis of Delgado’s life and opus leaves no doubt of his transcendence as a medical and social thinker, the most representative twentieth century’s Latin American psychiatrist and a true citizen of the world.

Born in Arequipa, Perú, Delgado showed early interest in medicine and left for Lima at age twenty-one to study at San Marcos University, the only medical school in the country. As a young faculty member he taught physiology and pathology using them as platforms for making medicine a solid, integrated set of human disciplines, what he called the “psychiatrization” of our profession. An expression of this perspective was his tenacious search, critique, testing and dissemination of every piece of new knowledge in medical theory and practice. His fluency in German, French, Italian, and English helped him access the most current scientific medical and psychiatric publications from other continents. Such was the context of his pioneering and vanguard-oriented contributions in areas as varied as psychoanalysis, biological psychiatric treatments, humanism, philosophy, medical education, or public health.

In the January 1, 1915, editorial page of El Comercio, the oldest Peruvian newspaper, Honorio Delgado, then a twenty-three year old San Marcos junior faculty, published an article titled El Psicoanálisis, considered the first on the topic aimed at the general Spanish-speaking public. His embrace of psychoanalysis was as enthusiastic and sincere as his desire to do everything possible for his patients. Appointed as Chief of Service at the first Psychiatric Asylum in Perú, he assisted his mentor, Hermilio Valdizán, in editing the first Latin American psychiatric journal, Revista de Psiquiatría y Disciplinas Conexas (1918–1924), which became a powerful Spanish-speaking voice for psychoanalysis. Soon thereafter, he initiated an active correspondence with Sigmund Freud1, who was so impressed by his knowledge and enthusiasm that he urged the members of his inner circle to invite Delgado to Europe. They first met in December 1922 in Weimar and Vienna, and again in 1927 at the 10th. International Psychoanalytic Congress in Innsbruck, followed by a visit to Freud’s Simmering countryside retreat, accompanied by Ferenczi, Eitington, and María Bonaparte. Delgado wrote heartfelt articles about these encounters, described warmly the deep personality traits and resiliency of the father of psychoanalysis in the face of physical ailments and attacks from enemies and dissidents of the new doctrine. Freud exchanged holiday and birthday cards with Delgado for several years and had many kind, admiring, humorous, and graceful remarks to make about the “first Latin American psychoanalyst.”

In 1921 Delgado published his first article in Imago, the official organ of the newly-born International Society of Psychoanalysis.2 As the first Latin American member of the Society, he translated several key books from German and English and was appointed member of the British Psychoanalytical Society in 1927, nominated by Ernest Jones. Gradually his objections to the Vienna School became more direct, questioning mainly its growing into a dogmatic, intolerant ideology, and its aversion to truly scientifically-based research for proofs of its theoretical assertions and therapeutic results. The distancing started in the late 1920s, the last correspondence piece was dated 1934, but even several years later Delgado wrote about Freud and psychoanalysis with respect and admiration.3

On the other hand, even in the heated years of his closest links with psychoanalysis, Delgado read and wrote about many important psychiatry and psychopathology topics. His approach to mental illness was “to use psychological criteria within the biological frame of general pathology”. This modern-sounding perspective, formulated in the 1920s, made him pay particular attention to the new biological treatments using malaria, cardiazol, and insulin as seizure-inducers in a then novel treatment of schizophrenia and other psychoses: he used them in Lima soon after their initial applications in Europe. During the 1930s he corresponded with Jaspers, Kretschmer, Kurt and Carl Schneider, and visited Heidelberg and Munich. He was also invited to visit von Jauregg, the first psychiatrist Nobel Prize winner (1927) for his introduction of malario-therapy in dementia paralytica. Delgado admired his concept of “efficacious medicine”, the fight to make everything practically possible to alleviate the patient’s suffering. Delgado’s innovativeness made of his Lima’s clinical research group (later called the Peruvian Psychiatric School), the first in the continent to use the brand new psychotropic agent, chlorpromazine, tried originally by Delay and Deniker in Paris in 1952. Within two years he obtained the medication, used it in a sample of Lima patients, and presented the results in Paris in 1955.4

In 1938, together with his contemporary Oscar Trelles, a renowned French-trained Peruvian neurologist, Delgado founded the Revista de Neuro-Psiquiatría, the oldest existing Latin American psychiatric journal. It became a tribune for cogent research contributions on a variety of themes. He continued laboring on a solid nosological structure for a psychiatry open to all orientations, accessible to clinicians, and precise enough to outline thorough clinical entities and research protocols. He made clear distinctions between psychosis and neurosis, disease and illness, symptoms and syndromes, personality and character, delusions, delirium, and delusional ideas. He articulated a “fundamental psycho-physio-pathology of schizophrenia” as disruption of conscience’s intentionality in the form of a “breaking of categories,” a disorder in the configurative role of experiences from the inner vs. the outer world, the ego vs. the content of consciousness, and this content vs. its categorical shapes: the three phenomena received the name of atelesis (e.g., deprivation of full objectives or consciousness power).5 He published his findings in prestigious European, North- and Latin American journals.* These works were the seeds of his Curso de Psiquiatría, first published in 1953, that reached five editions before his death in 1969 and even now is considered a classic for psychiatric trainees in many latitudes.

Delgado made possible the First International meeting for Latin American neuropsychiatrists (Jornadas Neuropsiquiátricas del Pacífico) that took place in 1937 in Santiago, Chile, its second version expanding into Jornadas Panamericanas, in Lima two years later, both remarkably successful. In 1950 Delgado was asked to speak on behalf of the American delegation at the opening ceremony of the First World Congress of Psychiatry in Paris. He was also official lecturer in the second World Congress, celebrated in Zurich in 1957. The same year he became a founding member of the Collegium Internationale of Neuro-Psychopharmacology.

Many of his writings had to do with the main missions of psychiatry as a medical specialty, a bastion of humanism, a social resource and a rich field of multidisciplinary research. His recognition by notable figures in the international scene had positive repercussions for Latin American psychiatry. As well, he became honorary member, visiting professor, and recipient of special distinctions from many scientific, professional, academic and specialty organizations, including the exclusive Royal Academy of the Spanish Language. He wrote over 400 articles, 40 books, hundreds of essays, chronicles, editorials and book reviews that reflected the universal scope of his academic interests.

He considered philosophy to be “altruistic wisdom” and “objective idealism”, and understood it both as the possibility of reflecting with freedom and lucidity over many issues of human interest, and as the option of executing actions based on sound ontological principles and ethical values. He wrote about the need of a thorough spiritual formation of any and every individual as a protection against the threats of the worst features of human nature; he reaffirmed, however, his faith in the ability of humans to overcome adversity, in the authentic physician’s potential access to “the soul” of his patients, defined as the open book of our aspirations, hopes, options and possibilities. He wrote path-breaking essays about ecology, inner/emotional time and human existence, the essence of authority and intellectual elitism; about what he called the “rehumanization” of scientific culture by means of a modern conception of psychology, while also claiming that the then growing discipline called psychosomatic medicine should not be another rendition of dogmatic or rhetorical sentences, or an aseptic set of existentialistic reflections. He advocated reading as an invaluable tool of cultural enrichment and, in what many consider proof of such assertion and his most eloquent book, De la Cultura y sus Artífices (On Culture and its Artificers) (1962), presented a scholarly collection of essays about the life and work of world thinking giants such as Gracián, Goethe, Ramón y Cajal, Proust, Castiglione, George, Jaspers, Hartmann, and others.

In short, Honorio Delgado ventured with courage, wisdom, vision, and brilliance into the world’s intellectual scene to provide his unique version of medical, psychiatric, and philosophic knowledge, and acquire without submissiveness but also without rancor what the world had to offer. It was said that his writing style reflected well his personal appearance: elegant, complex but accessible, formal and technical when necessary, solid and warm always. He elaborated his own epistemological synthesis beyond formal eclecticism, artificial superficiality, or a “know it all” blandness in order to build an original edifice of wisdom and authentic medical humanism. In his time, he gave Latin American Psychiatry the place and the recognition it truly deserved and which, in Delgado’s name, it should nowadays rescue.

Note

* Nervenarzt, Confinia Psychiatrica, Actas Luso-Españolas de Neurología y Psiquiatría, Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, L’Encephale, Anales Médico-Psychologiques, British Journal of Psychiatry, American Journal of Psychiatry, Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease.

References

- Delgado H. Freud y el Psicoanálisis. Escritos y Testimonio. Lima: Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Fondo Editorial, 1989.

- Delgado H.F. Der Liebesreisz der Augen. Imago: Zeitschrift fur Anwendung der Psychoanalyse auf die Geisteswissenschaften 1921; VII (2): 127-130.

- Delgado H. La doctrina de Freud. Revista Neuropsiquiatr 1940; 3: 9-44.4.

- Delgado H. Acerca de nuestras experiencias con la clorpromacina. Colloque International sur la chlorpromazine et les medicaments neuroleptiques en thérapeutique psychiatrique, Paris, Oct. 20-22, 1955. L’Encephale 1956; 4: 344-351.

- Delgado H. La psicopatología fundamental de la Esquizofrenia desde el punto de vista funcional. En: Contribuciones a la Psicología y a la Psicopatología, pp. 341-351. Lima: Peri Psyche Ediciones, 1962.

, MD, MPH is an Emeritus Professor of Psychiatry at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, MN, and a graduate of the Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia (UPCH), Lima, Perú. His post-graduate training was at Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD. Dr. Alarcón returned to Lima and was Associate Dean of the Medical School and Director of Academic Affairs at UPCH (1972–1979). He later worked at the University of Alabama, Birmingham; Emory University, Atlanta, GA; and the Mayo Clinic until 2012. He is currently finalizing three book projects, and he also assists trainees and young academicians in Lima and Rochester. His fields of interest are mood and personality disorders, psychiatric diagnosis, and cultural psychiatry.

Spring 2015 | Sections | Psychiatry & Psychology

Leave a Reply