Nod Ghosh

Christchurch, New Zealand

It begins when you are a child, in the pre-antibiotic dawn of an Indian summer, one of six siblings, five of whom will eventually die of broken heart valves or diabetes.

But let us say for now, you are a child, a child who loves to dance, to play in the gardens in Jalpaiguri, pulling fruit from trees, making up names for birds and insects. You dance to the tune of rain hammering the metal roof of your grandparents’ home.

Schoolboys tease you for the way you pull your embroidery thread, the way you draw your arm out so far. You grow into a young woman who learns to sing Rabindra Sangeet. You attend university, so rare for a girl at the time.

When you marry my father, it is your B.A. he sees, though he is not blind to your beauty. His parents have promised him to someone else. But he chooses you. He is unaware that a childhood infection has marked you and left you damaged.

When my siblings and I are born, the births are difficult, but you survive. My sister and I are ripped out, my brother extricated by caesarean section. His birth leaves a ladder of scars on your body. Later, the surgeon who replaces your faulty heart valve will add to the pattern.

You are prescribed warfarin and we joke about rat poison. You have never liked rodents. The brown pills have a line scored through the center. Sometimes you break them in half, but I do not understand why. “It’s to thin my blood,” you say, though that does not explain why sometimes you take two, sometimes two and a half.

The blood moves thickly through your veins, though not as thickly as before.

The cartoon image in my mind helps me make sense of it. Your blood is like warmed syrup, or a milkier porridge.

When I leave home, I am less enthusiastic than you were about gaining an education, perhaps because the motivation comes from my father, not me. But I graduate regardless. My father is not an easy man to disobey.

I learn about physiology. I learn about pharmacology. I learn about blood. I learn that the thickness of blood depends on many factors. I learn why this is important for people like you, whose blood eddies and stagnates in places it should not.

Through the years, the art of hematology lures me down its blood-lined path.

I show you vials of blood in the laboratory where I work. Red fluid sucked through tubes, rotated in centrifuges, curdled with chemicals. You watch a steel ball become enmeshed in the apparatus, and appear to understand my explanation.

“It’s to see how readily a person’s blood clots,” I tell you, conscious of your sari sweeping the detritus on the laboratory floor. I search for words to explain how warfarin changes things. You watch the indicator lights on the analyzer. Red LEDs like rats’ eyes.

The blood plasma turns thickly, and traps the steel ball.

Two tablets, sometimes two and a half.

Later we share a meal before you return to my father. I have become accustomed to his stony silences. He is not an easy man to please. He will not visit the laboratory.

“If only you had done something to make him proud,” you say, “not just a lab technician.” I flinch at the relegation of my status as a scientist, but I don’t correct you. I absorb the criticism, as if the responsibility for my father’s judgment is mine alone.

A wall forms between us like a hardened artery. It is fifty feet high. We rarely speak. I forget to ask about your warfarin, and you choose not to ask me about anything.

When my daughter is born, she is the catalyst that severs our ties for good. She is the glue that links me to my partner, the one you could not eradicate. I measure a person’s worth using different parameters. But how would I know what’s right?

Your blood flows like setting concrete through your circulation.

Blood is no thicker than water, and yet it sets like yoghurt between us.

My daughter has just turned eleven when you are admitted to hospital in India. Life has changed since you returned to your country of birth. Some things are better, others worse, but medical care in a semi-rural paradise is at the whim of the gods.

My eleven-year-old looks out of the aircraft as we land. Green. Yellow. Brown. She is engulfed by warm smells. The sounds of street sellers. The desperation of traffic. The howl of pariah dogs. The pathos of street urchins.

My father drives to the hospital in silence. You are conscious, but uncomfortable. One side of your face droops like melted plastic. You semi-smile at my child, though your eye-patch frightens her. The visit is painful for all of us.

“She’s bled into the base of her brain,” I tell my sister over the crackling international phone line. “It’s like a stroke. She’s lost power on one side of her face.” I wonder as I speak, whether it means you will have to learn to turn the other cheek in arguments.

“Her warfarin?” my sister asks, so I tell her you took too much.

My father and I visit you every day. He has few words, but confides his anxieties. We almost connect. We are almost like father and daughter ought to be. My confidence increases, and I venture deeper into the morass of confusion surrounding your overdosing. I ask how often you have your blood tests done. I ask about the laboratories you visit. The answers disturb me.

“She’s not been tested for some time,” he says.

I ask why.

“The clinics near us,” he continues, “they’re not good. The roads are really bad, too. She checks her blood herself.”

“How?” I ask.

“When she pricks her finger for her blood sugar.”

The answer leaps into my mind before he speaks again.

The blood pumps through my brain. It gushes through my inner ear. My cheeks redden with realization.

“When her blood looks a little thin,” my father says, “your mother cuts down on her warfarin.”

I am sinking.

“If it runs thick,” he continues, “she takes a little more.”

I showed you.

I showed you how we test for warfarin.

But how would I know what’s right?

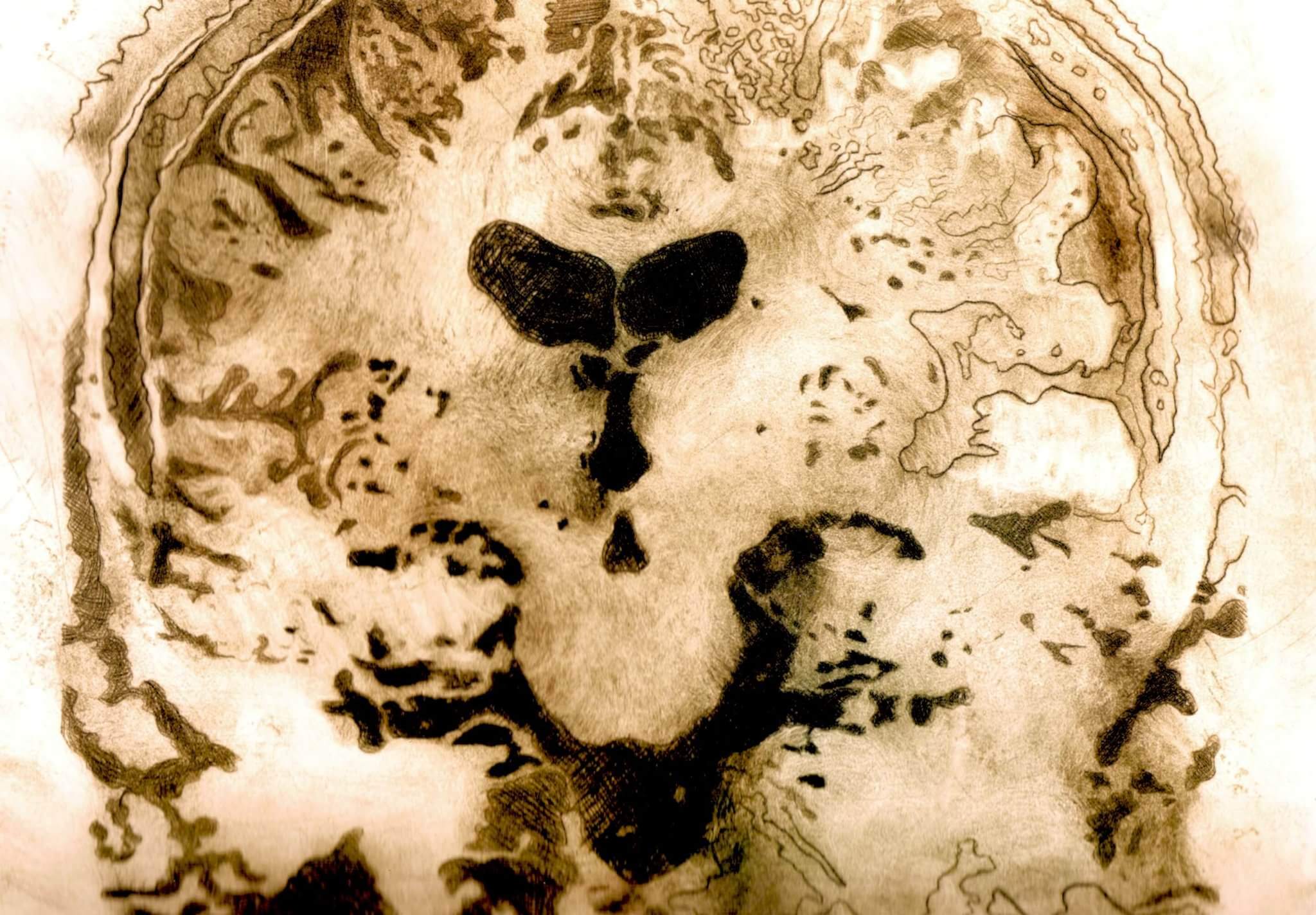

When you are well enough to travel, you leave India and come to us. Further tests reveal a tumor the size of a tangerine in your head. Fragile. Prone to bleeding, should your anti-coagulation go out of control.

Your neurosurgery is scheduled for early April. Your blood flows thickly through your veins. The surgeon cuts you behind your ear. Your blood flows thickly back again.

Tense and silent as mice, we pace in the relatives’ room. The surgery was long and complicated, but you have come through relatively unscathed. We thank the surgeon, the hero of the hour.

The next day, you bleed into your brain.

Within twenty-four hours you are brain dead. The coroner records your death as being caused by inappropriate treatment. You were given heparin within hours of surgery, and there are questions about whether the drug was given too soon.

I cannot hear anymore, as they determine what should have been done. I listen to the spaces between their words. I listen, hoping to hear your voice. But all I hear is silence.

NOD GHOSH is a Medical Laboratory Scientist at the immunophenotyping laboratory at Canterbury Health Laboratories in Christchurch, New Zealand. Nod’s written work features in various New Zealand and overseas publications. Nod is associate editor for Flash Frontier, an Adventure in Short Fiction.

Leave a Reply