George Dunea

Chicago, Illinois, United States

There was a doctor, and there was a baron. The doctor could write, the baron could fly. On a clear day the baron could have flown on the back of an eagle over Italy and Spain to the Carolinas and the White House. There was also a rogue professor. And there were actually two barons. The first was a generous host, who kept an open house and made up fantastic stories to entertain his guests. The second baron was the one who could fly. The professor was guest of the first and invented the second. The doctor read about the second and immortalized him in the Munchausen syndrome.

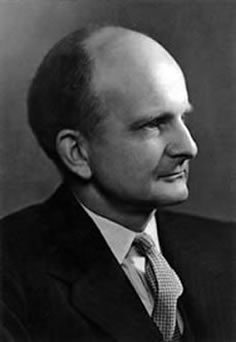

But alas, we live in an unheroic age. We cannot fly on eagles. We cannot slay our foes or throw down their ramparts by sneezing or sounding our trumpets. We can only reminisce. So it came to pass that working as a locum registrar in London and dictating some overdue patient discharge summaries, I heard someone from next door asking me to keep my voice down. I got up to see who it was. I saw a short balding man, screwdriver in hand, trying to repair an antique clock. Looking at the sign on the door during my retreat, I realized I had been in the presence of the author of the Munchausen syndrome, Dr. Richard Asher. I was awed.

So to leave the barons for later and commence with the doctor. He lived in an age when specialization was in its infancy. Most hospital consultants were general physicians, sometimes with an interest in a particular disease or organ. They were presumed to be masters at history taking, physical examination, and diagnosis. Many were also cultured. Versed in Latin and the classics, some wielded their pen as adeptly as their percussion hammers. To this category belonged Dr. Richard Asher, now remembered principally for the Munchausen syndrome and myxedematous madness.1,2

His was an era when doctors ordered their patients to bed for many weeks at a time, to rest their rheumatic hearts, swollen joints, or stomach ulcers. In “The Dangers of Going to Bed” Dr. Asher deplored this ill-advised practice and listed its complications, which now every medical student can recite: thrombosis and emboli, bed sores, pneumonia, muscle weakness and wasting, calcium draining from the bones, urinary stones, and difficulty in voiding urine. In men, “the horizontal position of the body coupled with nervousness and embarrassment” made using a bottle problematic. In the aged, constipation ruled supreme, and retained hard stools (technically scybala) could lead to diarrhea masking an underlying obstruction. Overcome by lethargy, many a patient confined to bed no longer cared to get up, resenting any “efforts to extract him from his stupor,” and leading a “vegetable existence in which, like a useless but carefully tended plant, [he] lies permanently in tranquil torpidity.”3

As doctors relied so heavily on examining their patients, Dr. Asher suggested it was also worth looking at their clothes.4 These could show signs of recent changes in weight, style, or behavior—stains on the trousers providing the explanation for hitherto mysterious skin ulcers caused by corrosive photographic fluid trickling down the work bench and seeping onto the patient’s thigh.4 Cultivating meticulously the art of observation would uncover early cases of Parkinson’s disease or hypothyroidism. The doctor was to note his patient’s color, how he talks, smells, walks, and lies in bed. The use of the senses could be taken even further, such as when a grave biochemist, a modern Areteus, once took a generous swig from a specimen of white fluid and declared without hesitation that did not taste like milk and therefore was not chylous ascites. On another occasion, an astute clinician noticed changes on a small patch of visible lung on a shoulder X-ray, leading to a diagnosis of pulmonary pneumoconiosis. Astute observation has given us penicillin and unveiled the cause of such ailments as dental caries and retrolental fibroplasias.5

But times were different, as was the spectrum of encountered illness, and diseases were seen at a more advanced stage. Imagine diagnosing an abdominal crisis of tabes dorsalis by correctly interpreting a complaint of “rheumatism” as the lightning pains of tertiary syphilis; aspirating pleural fluid by merely locating the area of greatest dullness on percussion; or finding decreased vocal fremitus and high-pitched aegophony over solid lung despite increased resonance. There were cases of mitral stenosis so advanced that the murmur and slapping first heart sound were more easily felt with the hand than heard with the stethoscope.5 Dr. Asher was a stickler about naming diseases.6 Without a name, he argued, many commonly observed phenomenona would never have made it into the textbooks. But a catchy name, preferably eponymous, has assured survival, even for the Pel-Ebstein intermittent fever, never attributed by either author to Hodgkin’s disease and probably due to chronic brucellosis.6 Well in advance of his generation, Dr. Asher argued for a critical evaluation of the effectiveness of treatments. Drugs should not be used merely because one thinks they should work, nor should one naively extrapolate from animal work or phony statistics, attribute spontaneous improvement to treatment, or prescribe, then as now, tons of vitamins to the credulous healthy and worried well.7

Not dull himself, Richard Asher thought the medical journals of his time were very much so.8 He disliked their black-and-white boring illustrations, their difficult to remove wrappers, their depressing advertisements of “elderly men in shabby pajamas hurrying along the passage with urinary frequency.” He complained of boring unattractive titles; and thought too many people had a desire for publication but nothing to say. Many authors wrote badly but “did not seem to realize they do,” using unnecessarily long words, writing always in the passive tense, “clogging their meaning with muddy words and pompous prolixity.” He hated boring dragging presentations of patient histories, preferring something more exciting, starting off with the most memorable part, such as a surgeon opening the abdomen and unexpectedly finding a large hole in the right diaphragm.8

From his medical pulpit Dr. Asher listed the main Seven Sins of Medicine,9 but suspected there were many more. Obscurity was due less so to an attempt to hide ignorance as to the bad habit of using Latin and Greek words that patients cannot understand. Cruelty was saying too much or too little to the patient, talking about him to students as though he was not in the room, treating patients as mere cases, often combined with bad manners towards patients, nurses, or colleagues, whether by impatience or inappropriate humor. Then came overspecialization, with a total indifference to other aspects of medicine and an inability to manage even the simplest case outside one’s chosen interest. It went with love of the rare, when only unusual cases excite the doctor’s interest. Sloth or laziness he also considered a sin, such ordering a battery of tests before completing a full history, physical examination, and assessment; as was common stupidity or medical automatism, the mindless adherence to fashions, guidelines, algorithms, for which not individuals but entire generations may someday burn in hell.9

Gottfried Franz

On the subject of hypnosis, or respectable hypnosis as he called it,10 Dr. Asher made only cautious claims. He viewed it not as the sport of music halls or the mysterious doings of a sinister man with strange piercing eyes, but rather an adjunct to treatment based on an exaggerated suggestibility produced by fixing the attention. It did not require an elaborate ceremony of mystery, but was to be no more impressive than seeing a dentist. He had used it in his office, with the patient relaxed on a couch and asked to look at the light of an ophthalmoscope bulb to allow him to concentrate on only one visible thing. He had found it occasionally useful in the treatment of warts, hyperhidrosis, eczema, alopecia, amnesia, and anxiety states. He made very modest claims, noting that only two out of five patients were deeply hypnotizable, that publicity and misuse by charlatans may have discouraged serious workers to study the value and limitations of the technique.10

Then there was the unforgettable description of myxedematous madness, the eminently reversible psychosis of advanced hypothyroidism.2 Having seen fourteen cases in four years, with psychotic delusions, paranoia melancholia, or depression, he worried there may be many other unrecognized cases. It affected mostly women, looking characteristically bloated, their facial contours smoothed away, little bags of edema under their eyes, skin yellow and waxy, hair dry and scanty, eyebrows scarce, the voice slow and fumbling with a nasal quality, giving the impression of “a bad gramophone record of a drowsy, slightly intoxicated person with a bad cold and a plum in the mouth.”2 It is clearly something to be on the lookout among the profusion of elderly persons housed in nursing homes nowadays.

But Dr. Asher’s main claim to fame is his description and naming of the Munchausen syndrome.1 He thought that few doctors had not been hoodwinked at some time by a “frequent flyer” with dramatic but not entirely convincing histories, often evasive in manner and hard to pin down, a wallet or handbag stuffed with doctors’ letters, insurance claims, and litigious correspondence, stories of many operations, scars on their bellies (abdominal type), bleeding from the lungs or stomach (hemorrhagic type), or seizures, headache, or loss of consciousness (neurological type). Impressive was the seeming senselessness of it all, the lack of apparent gain as in the malingerer, but possibly arising from an intense desire to deceive, a grudge against doctors and hospitals, a need to be the center of attention, or, less mundanely, to get drugs, escape from the police, or secure free board and lodgings for the night.1

Since the original naming of the syndrome, the literature on it has grown immensely. Many Munchausen patients have presented with chest pain (“cardiopathia fantastica”), have manipulated medical instruments to skew results, tampered with laboratory tests, and contaminated urine samples with blood or other substances. Psychiatrists have analyzed the syndrome and incorporated it into their diagnostic classifications. There is a Munchausen syndrome by Internet, in which people seek attention by portraying themselves gravely ill or victims of violence on social media. There is also a Munchausen disease by proxy, a form of child abuse described in an accompanying article in this issue.

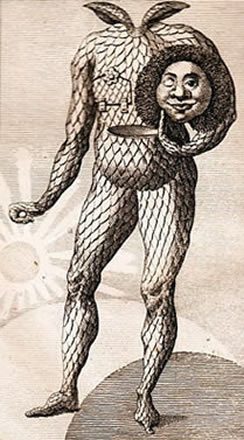

But what about the baron himself? The real one. He was Hieronymus Karl Friedrich von Munchausen, a veteran of a Brunswick regiment fighting in the Russian service army against the Turks. Promoted by the Empress Elisabeth to captain of the cuirassiers, he retired about 1760 to his patrimonial estate in Germany. There he lived pleasantly with his wife, maintained a fine pack of hounds, and kept an open house. To amuse his guests he would entertain them with wild stories that he had made up, and told them in a dry manner so entertainingly that in time some of people began to take them seriously. Among his occasional guests was Rudolph Erich Raspe, a learned professor, said to have been a genius but also a disreputable rogue. He had been born in Hanover in 1737, then the patrimony of the King Georges of England, perhaps accounting for his good command of English. Raspe had studied law and jurisprudence, worked as a librarian, clerk, and secretary to the university, then was promoted to professor in Cassel. He wrote voluminously on different subjects and was elected honorary member of the Royal Society of London. After misappropriating and selling some valuable coins abstracted from the university cabinets and entrusted to his care, he fled in 1775 to England. There he also had a mixed career, publishing learned volumes but also involved in several enterprises, some shady, resulting in him being struck of the rolls of the Royal Society. He eventually moved to Ireland, where he managed a copper mine, and died in 1794 of typhoid fever.

It is now accepted that Raspe was the real author of the fictional baron’s adventures. He got his idea from occasionally attending the real baron’s open house. He published his stories in London in 1785 as a brief pamphlet. Later he added more stories, largely culled from earlier medieval writers. More tales were added later by a person referred to as a booksellers hack. For 200 years the book has remained popular.11 Sadly, the original hospitable baron did not fare well from all of this. He became an object of curiosity and was visited by all kinds of people curious to hear about his adventures and perhaps expecting him to fly briefly to the moon and back.

The fictional baron did much better. He was roughly contemporaneous with the also fictional Lemuel Gulliver and Robinson Crusoe, and his fame has likewise endured. His adventures are worth reading about. When he fails to notice that his horse had been cut in two by the descending portcullis of a besieged town, he rides on until he gets to a fountain, where the horse displays such an insatiable thirst that the baron realizes that his horse has lost its hindquarters. In another story the baron used a sling from a balloon to lift high up in the air all the physicians present at the annual meeting of their college. He kept them there for over two months, so they could not attend to their patients. During that time the patients were none the worse for it, but the apothecaries, pharmacists, and undertakers experienced many bankruptcies.

References

- Asher R. Munchausen’s syndrome. Lancet 1951; i: 339–41.

- Asher R. Myxedematous madness. BMJ 1949; ii : 555–562.

- Asher R. The dangers of going to bed. BMJ 1947; ii: 967–968.

- Asher R and Smith R. It is worth looking at clothes. Arch Inter Med 1964; 114:33–35.

- Asher R. Clinical Sense. BMJ 1960; i:985–993.

- Asher R. Talking sense. Lancet 1959; ii:359–365.

- Asher R. Straight and crooked thinking. BMJ 1954; ii:460–462.

- Asher R. Why are medical journals so dull. BMJ 1959; ii:502–503.

- Asher R. The seven sins of medicine. Lancet 1949;ii:358–360.

- Asher R. Respectable hypnosis. BMJ 1956; i:309–313.

- Rudolph Erich Raspe. The surprising adventures of the Baron Munchausen. Pennsylvania, Wildside Press.

GEORGE DUNEA, MD, FACP, FRCP, FASN, is the president and CEO of the Hektoen Institute of Medicine. He is also a professor of medicine at University of Illinois at Chicago, the medical director of Chicago Dialysis Center, and founding chairman emeritus, Division of Nephrology, Stroger Hospital of Cook County. He also serves as Editor-in-Chief of Hektoen International.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Winter 2013 – Volume 5, Issue 1

Leave a Reply