Chris Arthur

Dundee, Scotland

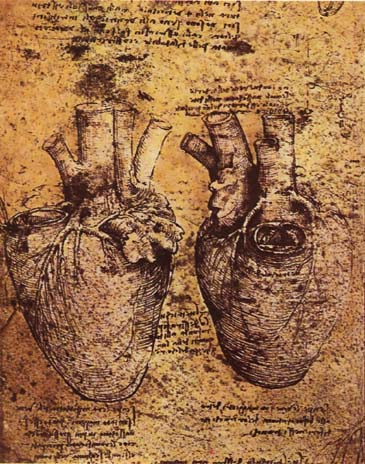

Among the most impressive of Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical studies are his drawings of the human heart. Beside one of them he has written: “How could you describe this heart in words without filling a whole book?” Since then, scores of books have been written about this most crucial of organs. We know a great deal more about its structure and function and the diseases that afflict it than in Leonardo’s time. But where our knowledge seems not to have progressed much in the last five hundred years is when we take the heart in a wider sense to mean the innermost part of us, what makes us tick—who in essence we are—rather than understanding it only as the fleshy pump that drives the blood around our bodies. Are we any wiser than people were in the sixteenth century about what impels one human heart to do good, another to visit heartless cruelty upon its fellows?

Outside the Civic Center in my hometown of Lisburn—eight miles from Belfast—there’s a statue of a man who experienced the worst that human beings can do to each other. Yet far from losing heart in the face of the atrocities he witnessed, he devoted his life to medicine. His pioneering work has been responsible for saving countless lives worldwide. It continues to save lives today. The statue is of physician and cardiologist Frank Pantridge, who was born nearby in 1916. Beside the statue, the sculptor has included a depiction of the small box that gives Pantridge his claim to fame—the portable defibrillator he invented in 1965.

The most striking thing about An Unquiet Life, Professor Pantridge’s memoir, is the contrast between the brutalities he encountered in wartime and the lifesaving initiatives he pioneered. As two of his medical colleagues put it, “he saw thousands die cruel deaths, but he went on to restore to useful life, often to full recovery, much greater numbers.”1 Today we have a detailed grasp of the subtleties of the heart’s engineering; our knowledge of its processes and diseases is highly sophisticated. But are we any closer to understanding what makes one person care for, and another bayonet to death, a patient lying injured in a hospital bed?

Pantridge completed his medical training at Queen’s University, Belfast, in 1939. When war broke out, he volunteered and was posted to Malaya as medical officer to an infantry battalion. His account of the fall of Singapore, and in particular the Japanese army’s savage execution of the wounded in one of the island’s hospitals, makes harrowing reading. Similarly grim are his recollections of being a prisoner of war working on the Siam-Burma railway. Many of his comrades perished, but Pantridge survived—despite contracting cardiac beriberi and being sent to the notorious Tanbaya death-camp. When he was liberated in 1945:

The upper half of his body was emaciated. The lower half was bloated with the dropsy of beriberi. But the most striking thing were the eyes that blazed with defiance. He was a physical wreck but his spirit was obviously unbroken. He weighed just under five stones [= 70 pounds or 31.75 kg].2

When he got back to Belfast, his first priority was “to pick up the threads of [his] medical career.”3 This he did with remarkable speed and success. Following a scholarship at the University of Michigan, where he worked with Frank N. Wilson, “the world authority in the field of electrocardiography at that time,”4 Pantridge became consultant physician at Belfast’s Royal Victoria Hospital. It is hard to know if there was a direct causal link between his experience of suffering from cardiac beriberi and his subsequent interest in coronary care. But one thing is certain. Pantridge returned from his grueling years as a prisoner of war with what fellow “railroad of death” prisoner Ronald Searle described as “a thorny and true measuring stick against which to place things that did and did not matter.”5 What mattered to Pantridge was saving lives. What did not matter were the entrenched views, bureaucracy, and lack of imagination that often stood in his way.

Recognizing that many of those who died from heart attacks did so simply because they did not receive rapid enough treatment, Pantridge argued for pre-admission use of defibrillators—in other words taking initial coronary care to the patient rather than waiting until they were hospitalized. To him it “seemed logical to try to correct [ventricular fibrillation] where it occurred—in the home, at work or in the street.”6 Following that logic meant moving away from the unwieldy hospital-based machines then in use. Instead, a portable defibrillator was needed. The earliest model, developed by Pantridge and his colleague John Geddes, along with Alfred Mawhinney, a hospital technician, weighed 70 kg and ran off two 12-volt car batteries. Soon this cumbrous device was refined, eventually evolving into the handheld defibrillators with which we are so familiar today.

Given the way in which these devices have become a standard piece of medical kit— found not only in ambulances but in offices, airlines, hotels, shopping centers, sports clubs etc.— it is easy to forget that only fifty years ago they were virtually unknown. Their very ubiquity masks their far from unproblematic birth. It was Pantridge’s vision and determination that led to their invention, development, and increasingly widespread use. But to begin with he faced considerable skepticism from the medical establishment. The Association of Physicians of Great Britain and Ireland, for example, gave his work a hostile reception when it met in Belfast in 1967. It took almost a quarter of a century before his radical idea of using ambulances as mobile coronary care units became the accepted orthodoxy in Britain. Reaction abroad was more favorable. In America in particular, his innovations were given a sympathetic reception. As Barry Shurlock puts it, Pantridge’s ideas “crossed the Atlantic Ocean more easily than the Irish Sea.”7

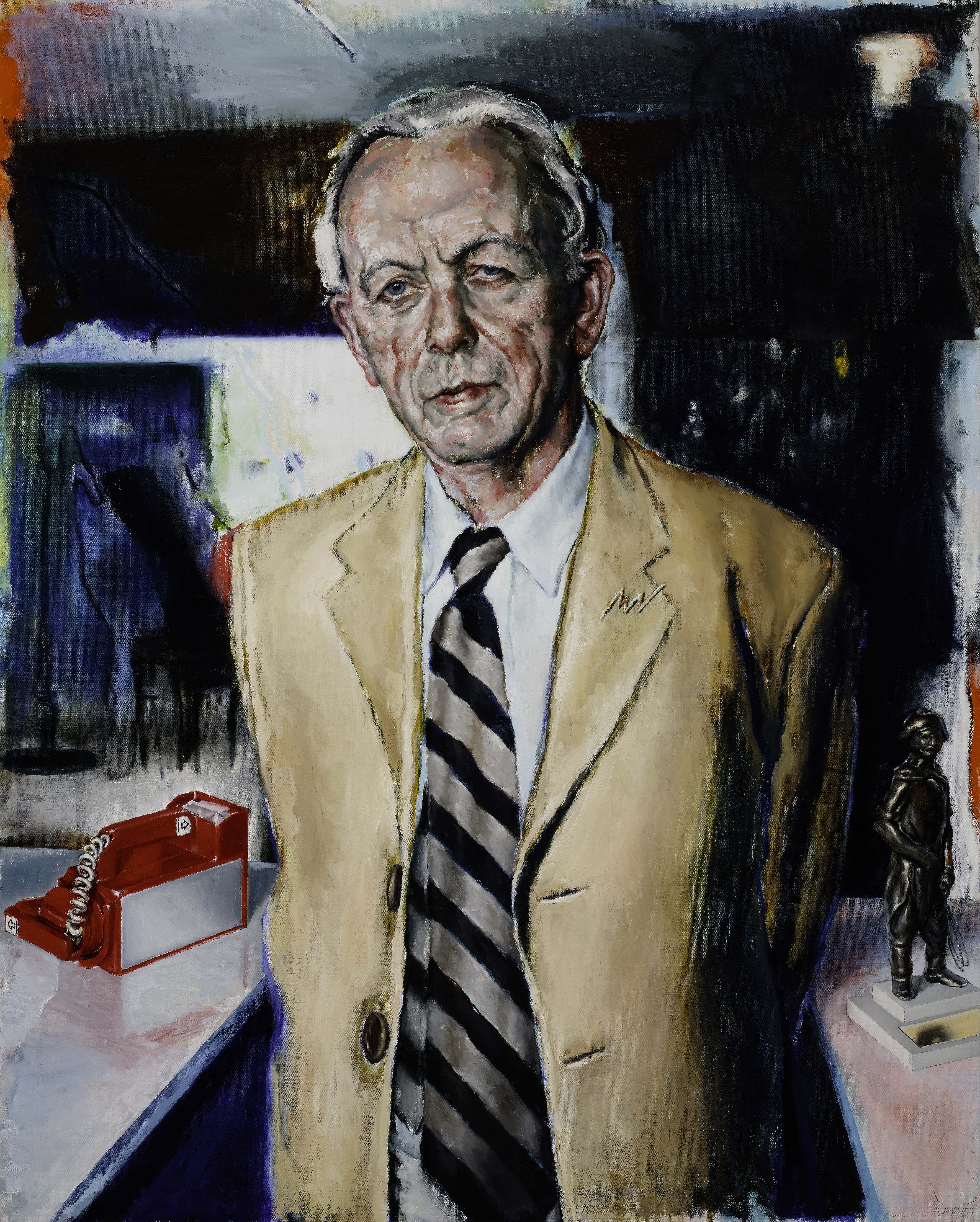

In 1999, when he was guest of honor at a Latin-American congress on Pre-Hospital Coronary Care, Pantridge sent a postcard to a friend in Belfast saying “I seem to be better known in South America than I am in Northern Ireland.”8 There are some encouraging signs that he is at last starting to gain some recognition in his homeland. In addition to the statue outside Lisburn’s Civic Center, two roads and an army medical base have recently been named in his honor, and his alma mater now has a commissioned portrait of this distinguished graduate hanging in the University’s Great Hall. But he is still far from being a household name. Although he was born only a few miles from where I grew up, and although I attended the same Quaker school that he did (Friends’ School Lisburn), it is only recently that I’ve become aware of the extent to which this pioneering cardiologist deserves the soubriquet “father of emergency medicine.”

Whilst lamentable, my ignorance is not atypical. On the contrary, most of Pantridge’s compatriots have little or no grasp of the scale of his achievement. In part, this may just be a case of a prophet not being honored in his own country. The date of Pantridge’s death—December 26, 2004—may also be a factor. It received scant media attention because it coincided with the tsunami that devastated so much of Southeast Asia on that day. But I suspect that this lack of recognition stems mostly from the way in which we too often let bad things obscure our view of what is good. If Pantridge’s invention and use of portable defibrillators had happened in London, say, or Washington or Paris, it would surely have gained public recognition more quickly than it did. In Belfast, the city’s aura of violence acted like a set of blinkers, making it hard to see that alongside all the terrorist atrocities there was someone piloting an innovative medical program with the potential to save many lives.

One of the saddest books I know is Lost Lives.9 It records the stories of everyone who died in Northern Ireland’s Troubles, providing a painstaking directory of the 3,600 deaths that constitute the human cost of this conflict. Things in Northern Ireland have much improved since Lost Lives was published. Nonetheless, not only is that period of the country’s history so dominated by violence that it can give the impression that bombings and shootings were the only things that were happening, but even now “Ulster,” “Northern Ireland,” and “Belfast” can act like prompts whose mention brings to mind images of mayhem and murder rather than medical advance.

To counteract such a view, I like to imagine a multi-volume book entitled Saved Lives. Its pages would catalogue every life prolonged by the portable defibrillator. I know that nothing can atone for the tragedy of lives cut short before their time, but such a publication would surely offer healing balm for the sadness and savagery that are so heartbreakingly chronicled in Lost Lives and An Unquiet Life. If we want to understand the heart that beats within us, the heart whose secrets Leonardo yearned to know, we must take care not to let its undoubted propensity for violence cast such a shadow that it prevents us from seeing anything beyond it. Frank Pantridge is an inspiring example of how one person can make a difference. His life story offers a kind of cognitive defibrillator. It helps restore a balanced view whenever acts of barbarism dominate the news and threaten to distort our perception of humanity.

References

- [Mary G. McGeown & A.H. Garmany Love, writing in their Introduction to Frank Pantridge, An Unquiet Life: Memoirs of a Physician and Cardiologist (Antrim, NI: Greystone Books, 1989), xix.

- This is Tom Milliken’s account, quoted by McGeown & Love in their Introduction, x-xi. Milliken was medical officer on a hospital ship sent to Singapore to bring POWs home. He and Pantridge had been students together. Understandably, Milliken was shocked by his friend’s condition.

- An Unquiet Life, 47.

- Ibid., 56.

- Ibid., 44. “Railroad of death” is Pantridge’s term. Ronald Searle went on to become a celebrated satirical cartoonist and creator of the “St Trinians” books.

- Ibid., 86.

- Barry Shurlock, “Pioneers in Cardiology: Frank Pantridge, CBE, MC, MD, FRCP, FACC”, Circulation: European Perspectives in Cardiology, December 18/25 2007, 145 [http://circ.ahajournals.org/].

- Alun Evans, obituary in the British Medical Journal, 31st March 2005 [http://www.bmj.com/content/suppl/2005/03/31/330.7494.793.DC1].

- David Mckittrick et. al., Lost Lives: The stories of the men, women and children who died as a result of the Northern Ireland Troubles (Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing, 1999)

CHRIS ARTHUR’S five essay collections are: Irish Nocturnes, Irish Willow, Irish Haiku, Irish Elegies, and On the Shoreline of Knowledge. Words of the Grey Wind, a new and selected essays volume, appeared in 2009. His work has been included in The Best American Essays and frequently mentioned in the ‘Notable Essays’ lists of this annual series. He was awarded the 2015 Monroe K. Spears Essay Prize.

Leave a Reply