William R. Albury

George M. Weisz

New South Wales, Australia

The “Toulouse-Lautrec Syndrome”

Renowned 19th century French painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s most obvious association with medicine is through his bone disease. The condition from which he probably suffered was first described in 1954 by the French physician Robert Weissman-Netter. It was named pycnodysostosis in 1962 by Marateaux and Lamy and was soon attributed to this artist as the “Toulouse-Lautrec Syndrome.”1 The retrospective diagnosis of his skeletal condition is highly probable but cannot be definitive, as no autopsy was done when he died, no x-rays were taken of his bones during life, and there has been no subsequent exhumation of his remains to allow post-mortem studies to be carried out.

Pycnodysostosis—from the Greek puknos (dense), dys (defective), and ostosis (condition of bone)—is a hereditary autosomal recessive dysplasia caused by an enzyme deficiency, namely of cathepsin K (cysteine protease deficiency in osteoclasts), reducing the normal bone resorption and leaving an incomplete matrix decomposition.

The cathepsin deficiency in osteoclast diminishes the normal bone turnover balance, leading to bone quality deterioration and fragility. The defective CTSK gene was identified on chromosome 1q21, being a very rare disease (found only in a few hundred on Medline search).2 The bones although hyperostotic, are brittle, the distal phalanxes of fingers and toes undergo acro-osteolysis (fragmentation and resorption), with sclerotic skin changes. Various medical treatments, such as growth hormone or calcitonin, have reportedly been successful in increasing linear bone growth.3 Stem cell transplantation, attempted in the management of other osteoclast diseases, has not as yet been reported in pycnodysostosis.

Despite bone deficiency, the healing of fractures in pycnodysostosis is almost normal. Intra-medullary nailing is possible as the canal is not stenotic, as in osteopetrosis.4,5 Particularly interesting are the recent publications of spinal abnormalities in this disease: segmentation changes with resulting scoliosis, fractures in pedicles and laminae, and isthmic spondylolysthesis.6,7

Toulouse-Lautrec had a short stature with shortened legs, a large head due to a lack of closure of the fontanellae (which he usually covered with a hat), a shortened mandible with an obtuse angle (covered with a thick beard), dental deformities that required several surgical interventions, a large tongue, thick lips, profuse salivation, and a sinus obstruction with post-nasal drip. With fractures of the long bones during childhood, later on of the clavicle, with progressive hearing problems and cranio-facial deformities, Lautrec’s condition would complete the diagnosis of pycnodysostosis.

Lautrec’s hands have been analysed in photographs, since they provide the only objective proof of deformities. In his twenties the hands were large, the distal phalanxes of the fingers short. Our additional observation, not previously reported, is that his hands in later years showed a thick sausage type of middle phalanx and proximal phalanxes much thinner than in earlier photos (Fig. 1 & 2) and had a very atrophied (thinned) hands seen in the last few months of his life.

The Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa dynasty

Since pycnodysostosis is a recessive disorder, the defective gene must be passed on by both parents in order for the condition to appear in their child. Thus the history of the artist’s family is highly relevant to the question of his retrospective diagnosis.

Count Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa descended from two aristocratic families dating back to the Crusades, who had lived for centuries in the south of France. The Monfa families were provincials, engaged in the usual leisurely preoccupations, wandering from one estate to another castle, and frequently intermarrying. Lautrec’s grandmothers were sisters and his parents were therefore first cousins.

Several congenital deformities are recorded in the family. For example, Lautrec’s first cousins, three sisters, were all dwarves with severe extremity deformities, relying on crutches or not walking at all, but living nonetheless until adulthood. Their parents were the sister of Lautrec’s father, married to her cousin, his mother’s brother. Many children in the family died in infancy, something not uncommon in those centuries. One such was his brother, who lived to be about one year old.

Childhood medical history

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was born on November 24, 1864 after a prolonged but otherwise normal labour. As a child he was boisterous and happy, drawing animals before he learned to write. Several illnesses were mentioned in the numerous scripts on his childhood, such as measles and later in life jaundice, rhinitis, and repeated respiratory infections.

His first accident at age 13 and half (May 30, 1878) led to a fracture of the left femur, treated by plaster immobilization and healing without delay. The right femur was broken a year later (in July or August 1879). The dates for this injury are slightly varying in different sources, and so are the sites of the fractures, whether thighs or legs. The French word for leg “jambe” was soon identified as “femur” by Lautrec’s father. This second fracture healed only after immobilizing the leg in a “gouttière,” a metallic tunnel, and silicone “plâtre,” French word for plaster cast, but without surgical intervention.8

Lautrec recovered and resumed his activities, but his walk permanently remained wobbly and a stick was required for support. It is possible that the fractures occurred at the lower end of the femurs and might have affected his epiphyseal growth plates. He reached 151cm in height and had short legs. (Fig. 1) He was reported to have “valgus” (knocked) knees, covered up in adulthood with several layers of pants, but this deformity was not as yet evident in a photograph of him at the age of five.

These accidents were conveniently accepted by the parents as the causes of his short stature. In fact there is a long history, since the age of seven, in which “for painful legs” and “swollen ankles,” he required a stick for walking. As a child he received extensive treatment in a Paris hospital, lasting over a year, with tractions, manipulations, and massages, but with no success. He was exposed to frequent balneotherapy at the age of ten, and passed through Lourdes in order to pray for a miraculous recovery at the local “healing grotto.”

Life as an artist

Once mobile, Henri progressed in his studies with spirit and determination until matriculation. He had a good intellect and advanced well in Latin and English, with a self-deprecating humour. He moved to Paris to attend an art school, and remained in that city for the rest of his life. He initially followed Degas, van Gogh and Pissarro, but soon developed his own artistic style, continuing from the “plein air” painting to Post-Impressionism.

In Paris, as an adult, he moved to the bohemian and red light quarters of Montmartre, living with and depicting the life of workers, cabaret dancers, theatre actors, circus performers, vagabonds, and prostitutes. Despite his restricted mobility, he participated in various recreational activities such as boating, swimming, and cycling. He also travelled frequently in Europe (Belgium, Holland, Spain), even crossing the Channel.

During his adult life, he produced in just 15 years, 737 paintings, 275 watercolours, 368 prints and posters, as well as sculptures, ceramics and stained glass windows.

Toulouse-Lautrec’s connections with medicine

First, Dr. Henri Bourges, a close academic friend, was a physician with whom Toulouse-Lautrec shared an apartment for six years. Lautrec made a full-sized portrait of his caring friend (now in the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh). Their close association had a negative consequence because Dr. Bourges was hospitalized for tuberculosis and was probably the person from whom Toulouse-Lautrec contracted the disease.

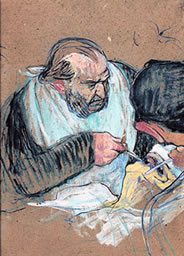

Secondly, the artist was almost totally dependent on another doctor, namely his cousin, Gabriel Tapie de Celeyran, also depicted in a life-sized portrait (now in the Musée Toulouse-Lautrec, Albi). In addition to looking after him on a daily basis, Tapie de Celeyran introduced him to Hopital International, where he painted famous physicians such as the virtuoso surgeon, Jules-Emile Péan. In 1891, in Une opération aux amygdales, Péan is depicted with a napkin around his neck, the patient with a mask on his nose (presumably with ether or chloroform) and an open mouth, with a clamp introduced by a surgeon without gloves, which were not in general use at the time. (Fig. 3)

Thirdly, Toulouse-Lautrec’s most important connections with medicine were his various diseases. His bone disease has been discussed above, but he also suffered from other severe conditions.

One such condition was chronic alcoholism, a response to his emotional problems resulting from his deformities. In later years he became arrogant, aggressive, and burdened with hallucinations and paranoia. He collapsed into a delirium tremens, was admitted to a sanatorium and forcibly detoxified. His faithful childhood friend Maurice Joyant (who remained with him till the end and became the administrator of his estate and the initiator of the Toulouse-Lautrec Museum in Albi), visited him in the hospital and was deeply affected by his condition. However Lautrec recovered from his psychosis within three months, and after review by three psychiatrists (Drs. Dupré, Seglos and Semelaigne) was declared “ameliorated with no symptoms,” but with memory problems. He was discharged and soon relapsed into drinking, although there is no evidence of recurrent psychosis.8,9

Lautrec’s cerebral alcoholism was further complicated by syphilis, contracted at the age of 22. In later years he had seizures and a stroke with hemiparesis (or hemiplegia in other sources), but he was able to paint almost to his last days. In August-September 1901, he depicted his cousin Gabriel’s final doctoral examination: Un Examen à la Faculté de Médecine de Paris in 1901, with the candidate sitting in front of two examining professors (now in the Musée Toulouse-Lautrec, Albi). It was to be his last heroic painting, for he was soon to succumb to his illnesses, in the southern region of France where he was born. He died just two months before his thirty-seventh birthday.10

Cause of death

All of Toulouse-Lautrec’s serious diseases may have contributed to his premature death. Cerebral alcoholism of Wernicke-Korsakoff type is progressive and permanent, with psychosis, all due to brain intoxication, malnutrition and vitamin B1 deficiency, which is unlikely to have been his case. A debilitating, general weakness often described, was progressive. Nonetheless, it is recorded that just two days before his death, Lautrec walked to open the door for a visiting priest, and that in his last moments he was conscious; he recognized his generally absent father who came to visit him on his deathbed and cynically insulted him with his last two words.9,10

Neurosyphilis would be another serious illness which leads to cerebro-vascular pathology; it is permanent, with stroke type of illness or progressive dementia. None of these were recorded as permanent in Lautrec’s case. Later on he was “dragging his legs,” possibly a sign of tabes dorsalis, or hemiplegia, but not described as permanent.8,9

It is our contention that, although the various diseases from which he suffered all contributed to his death, it is likely that tuberculosis, contracted during his prolonged cohabitation with Dr Bourges, was the principal cause of his premature death. Supporting this hypothesis is the description of him “coughing up blood” and experiencing frequent “nose bleeds”—both corresponding to the diagnosis of “consumption” made by “several experts just three months before” his death, as reported by his father Alphonse Lautrec.11

Despite his tragic life, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec triumphed over his infirmity through his art, and his name became immortal.

References

- Maroteaux P, Lamy M. La picnodysostose. Press Med 1962; 70:999-1002; and JAMA 1965; 19 (9): 715-717.

- Toral-Lopez J, Gonzales-Huerta LM et.al. Familial pycnodysostosis: identification of a novel mutation CTSK gene (cathepsin K). J Investig Med 2011; 59(2):277-280.

- Soliman AT, Rajab A, et.al. Defective growth hormone secretion in children with picnodysostosis and improved linear growth after growth hormone treatment. Arch Dis Child 1996; 75(3):242-244.

- Bor N, Rubin G, et.al. Fracture management in pycnodyostosis: 27 years of follow up. J Pediatr Orthop B 2011; 20(2): 97-101.

- Nakase T, Yasul N, et al. Surgical outcomes after treatment of fractures in femur and tibia in pycnodysostosis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2007; 127(3):161-165.

- Floman Y, Gomori JM, et al. Isthmic spondylolysthesis in picnodysostosis. J Spinal Disord 1989; 2(4):268-271.

- Beguiristain JL, Arriola FJ et al. Lumbar spine anomalies in a pycnodysostosis case. Eur Spine J 1995; 4(5):320-321.

- Joyant M. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. New York: Arno Press, 1926.

- Denvir B. Toulouse-Lautrec. New York and London: Thames & Hudson, 1989.

- Frey JB. Toulouse-Lautrec, a life. New York: Viking, 1994.

- Schimmel HD. The letters of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Count Alphonse’s letter to René Princeteau (4.9.1901). New York: Oxford University Press, 1991: 411.

WILLIAM R. ALBURY, PhD, is adjunct professor of History in the School of Humanities at the University of New England in Armidale, NSW, Australia. His principal research interests are the history of science and medicine (ca. 1500-1900), Renaissance intellectual history, and social history as reflected in works of art. His most recent publications in these areas are: G. M. Weisz, W. R. Albury, Donatella Lippi and Marco Matucci Cerinic, “Who Was Pontormo’s Halberdier? – the Evidence from Pathology,” in Rheumatology International; W. R. Albury, “Castiglione’s Francescopaedia: Pope Julius II and Francesco Maria della Rovere in The Book of the Courtier,” in Sixteenth Century Journal; and W. R. Albury and G. M. Weisz, “St. Joseph’s Foot Deformity in Italian Renaissance Art,” in Parergon.

GEORGE M. WEISZ, MD, MA, FRACS, is adjunct senior lecturer in the School of Humanities at the University of New England in Armidale NSW, Australia, and in the School of Humanities at the University of New South Wales in Sydney NSW, Australia. He trained as an orthopedic and spinal surgeon in Israel, the USA, and Canada. He has been in practice in Sydney since 1975. His interest in history and the arts led to a BA degree in European History at the University of New South Wales and to an MA in Renaissance Studies at the University of Sydney. His present research continues on both medical and historical lines, more specifically on “ghetto doctors’ contributions to medicine” and “medical history hidden in Renaissance paintings.”

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 5, Issue 3 – Summer 2013 and Volume 14, Issue 4 – Fall 2022