C. John Scott

Aberdeen, Scotland

The epidemic of childbed (puerperal) fever that struck the city of Aberdeen, Scotland, between December 1789 and March 1792 was unusual. It occurred not in the dirty, crowded, and ill-ventilated wards of lying-in hospitals, but throughout the city and surrounding villages. Serendipitously, one doctor cared for most of the patients. This was Alexander Gordon, physician to the Aberdeen Dispensary, a position analogous to a present day general practitioner. Gordon was not a simple provincial practitioner but a doctor with wide experience in medicine and specific training in obstetrics. He used his knowledge and experience to identify the means of transmission and proposed preventive measures for the disease half a century before Oliver Wendell Holmes and Ignaz Semmelweis.

Gordon was son of a farmer at Milton of Drum, a few miles west of Aberdeen. He studied at Marischal College, Aberdeen, between 1771-5 and then began medical studies at Aberdeen Infirmary. University medical teaching in Aberdeen at that time was poor, so he continued his studies in Edinburgh and Leyden. He did not graduate, but learned sufficiently for him to obtain a Certificate of Proficiency from the Company of Surgeons, which allowed him to join the Royal Navy as a surgeon’s mate in 1780. He was promoted to surgeon in 1781. In 1785 he retired from the navy on a half pay pension and spent nine months in London getting instruction and gaining experience in midwifery. He may already have planned to return to Aberdeen as he would have known that there was no doctor in the city with obstetric experience. He moved back to Aberdeen in 1785 and was appointed physician to the Aberdeen Dispensary in 1786. He was awarded MD from Aberdeen in 1788.1

When an outbreak of puerperal fever began in Aberdeen in 1789 Gordon recognized it for what it was, having seen cases in London hospitals, but he had no more idea than any other doctor of the time as to what caused it and how it was transmitted. Getting up too soon after childbirth, too rapid a delivery, changes in the weather, strong drink, spices, metastasizing milk, and obstructed perspiration had all been suggested. Perhaps the most popular belief was that it arose from poisons in the atmosphere (miasma). This would have been credible for outbreaks in hospitals, but seemed to Gordon unlikely for an outbreak in a scattered community affecting women of all classes and a variety of living conditions. He noted that women in outlying villages who were delivered by local midwives did not get the disease, whereas if a city midwife was involved in the birth most were affected. Using Dispensary records and his own notes he was able to construct a table of almost all cases, in which he recorded which health professionals had been involved and the date the disease had its onset. Thus he was able to track the course of the disease from patient to patient via a midwife or a doctor. His findings, which he published in 1795, both surprised and shamed him.2

He found that “this disease seized such women only as were visited or delivered by a practitioner or taken care of by a nurse who had previously attended patients affected by the disease.” So certain was he of this that he “could venture to foretell what women would be affected with the disease upon hearing by what midwife they were to be delivered.” It was not only midwives who transmitted the disease. He admitted, “I myself was the means of carrying the infection to a great number of women.” He went on to recommend, “Nurses and physicians who have attended patients afflicted with the puerperal fever ought carefully to wash themselves and get their apparel properly fumigated before it be put on again.”

Gordon deserves recognition as the first doctor to appreciate the contagious nature of puerperal fever and its prevention by hygiene of health professionals. Unfortunately, his treatment by vigorous bleeding and purging can only have done harm. Although an original thinker, he was also a doctor of his time.

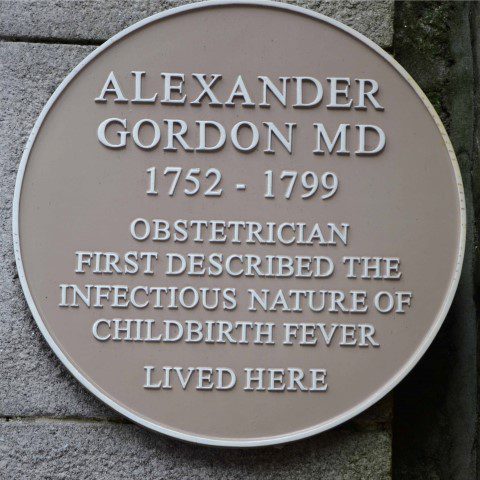

Neither life nor history treated Gordon kindly. He left Aberdeen in 1795 when recalled to the navy. This must have been a relief to him. By then medical colleagues, midwives, and the public of Aberdeen were openly hostile to his ideas. He never again practiced midwifery. His contribution to medicine has been overshadowed by the more heart-rending story of the life, suffering, and death of Semmelweis. He died of tuberculosis aged forty-seven years shortly after ill health forced his retirement from the navy. No likeness of him exists and the only public memorials in his home city are a small plaque on the house he occupied and a neglected gravestone in an Aberdeen churchyard.

References

- Porter Ian A. Alexander Gordon MD of Aberdeen 1752-1799. University of Aberdeen:Oliver and Boyd (Edinburgh), 1958.

- Gordon, Alexander. A Treatise on the Epidemic of Puerperal Fever of Aberdeen.London:GG and J Robinson, 1795.

C. JOHN SCOTT, MB, BS, MBA, FRCP (Edinburgh), FRCP (London), graduated in medicine from the University of Newcastle, England, in 1968 and undertook postgraduate training in Edinburgh until appointed Consultant Physician in Geriatric Medicine to Grampian Health Board and Clinical Senior Lecturer, University of Aberdeen, Scotland, in 1976. His clinical interests were care of the elderly, and rehabilitation and management of younger people with disabilities. Since retirement in 2004 he has worked with several voluntary organizations concerned with elderly people and people with physical and learning disabilities, and has published several papers on medical biography and history.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 7, Issue 2 – Spring 2015

Leave a Reply