Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

“The organism which is destroyed by prolonged hunger is like a candle which burns out: life disappears gradually without a shock to the naked eye.”

– Emil Apfelbaum, M.D., prisoner in the Warsaw Ghetto

Nazi Germany invaded Poland in September 1939. One year later, the 450,000 Jews of Warsaw were confined to a 1.3 square kilometer walled-off prison. The ghetto, where overcrowding, inadequate water supplies, and inadequate food were the rule, became the site of “the most extensive investigation of starvation ever carried out.”

In April 1941 the Nazis ordered the caloric provisions for the inmates of the ghetto to be “less than the minimum for preserving life.” The official Nazi daily caloric allowance in Poland was 2,600 kcal for Germans, 699 kcal for Poles, and 180 kcal for Jews. The usual caloric requirement for adults is 2,000 to 2,500 kcal per day. By the end of 1941, all food reserves that supplemented the inadequate caloric provision authorized by the Nazis had been depleted.

The extent of starvation, despite a thriving black market and soup kitchens set up by charitable organizations, was staggering. When horsemeat was no longer available, people ate coagulated horse blood seasoned with salt and pepper and spread on bread. In one incident, a woman jumped from a window and landed on a large cauldron in which fish were cooking. Her blood and pieces of her brain mixed with the fish. Starving children ran out from their hiding places to eat handfuls of this mixture. A mother, driven insane by hunger, was seen “gnawing on her dead child.” The prisoners of the Warsaw Ghetto became blasé about seeing dead bodies in the street.

Ghetto inmate Dr. Israel Milejkowski wanted to leave a “scientific record of the extent of the starvation” and began a study of the effects of hunger. He began in February 1942 in the two poorly equipped hospitals still left in the Warsaw Ghetto. Twenty-two of the ghetto’s twenty-eight physicians took part in the study. Patients were divided into two groups: children from six to twelve years old and adults between twenty and forty. The study had two phases. In phase one, all patients admitted to the hospital with a primary diagnosis of “hunger disease” were examined and findings noted. “Hunger disease” meant having a caloric intake of fewer than 800 kcal per day (for adults) and no other disease. For children, the definition of low caloric intake was based on the child’s age. In phase two, metabolic and cardiovascular effects, as well as behavioral, ophthalmologic, dermatologic, and immunologic effects were studied.

From early 1940 (well before the study started) until July 1942, 3,600 autopsies were performed by physicians in the Warsaw Ghetto. Five hundred were performed on victims who died “only” of starvation without other complicating factors. The average weight of adults on an 800-kcal diet was thirty to forty kilograms, that is, no more than half of their pre-starvation weight. One thirty-five-year-old woman with a height of 152 cm weighed only 24 kg.

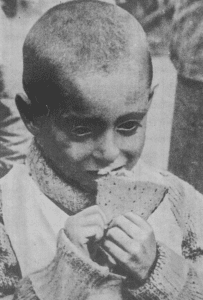

In children, the earliest signs of starvation were apathy, slow movement, and no interest in play. They were sad and became quarrelsome, and intellectual development stopped. At the most advanced stage of starvation, they took a fetal position. All patients had metabolic slowing with decreased body temperature and heart rate and slow, shallow respirations.

Starvation caused patients to first use up liver and muscle glycogen stores, then body fat. Depending on the individual, fat stores could last from weeks to months. After that, protein broke down and led to muscle wasting. With refeeding, the adaptations to starvation did not reverse evenly. While metabolic changes reversed quickly, cardiac changes reversed more slowly, leading to heart failure. Over 100,000 people died in the Warsaw Ghetto from disease (often typhus), starvation, or a combination of both.

In July 1942, five months after the study started, mass deportation began from the Warsaw Ghetto to the Treblinka concentration camp. The ghetto hospitals were burned and all medical equipment destroyed. A manuscript was produced from the study data and smuggled out to Professor Witold Orlowski, head of the department of internal medicine at a university hospital in Warsaw. In 1945 Dr. Emil Apfelbaum, a former inmate of the Warsaw Ghetto, got the manuscript from Dr. Orlowski and had it published. Polish and French versions were published in 1946 and an English translation in 1979.

One vital piece of information in the manuscript was that emaciated survivors of starvation should be refed slowly and with small amounts. The deaths of some concentration camp survivors who had been liberated and refed by Allied troops might have been prevented if this information had been available.

Dr. Milejkowski, the study originator, died in Treblinka in 1943. Few of the physicians involved in the study survived the war.

References

- Erwin Rugendorff. “The Hunger disease study in the Warsaw Ghetto,” The Scope of Urology–Didusch Museum, 2, Summer 2020. urologichistory.museum

- Charles Roland. “Scenes of hunger and starvation, ch. 6” In Courage under Siege: Disease, Starvation and Death in the Warsaw Ghetto, New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Martin Gumpert. “The physicians of Warsaw,” The American Scholar, 18 (3), 1949.

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D., was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan.

Leave a Reply