Stephen A. Klotz

Justin O. Schmidt

Tucson, Arizona, United States

Every Monday afternoon after returning to my office from infectious disease clinic, I would find pickle jars and yogurt containers on my desk. Upon removing the lids and peering in, I saw crawling over one another the largest kissing bugs in the United States. There was always a note on the lid from Lee McElroy detailing in whose home the bugs had been captured and how many people were bitten. Throughout June and July, she dropped containers off on Monday mornings, driving ninety miles from Bisbee to Tucson, Arizona. Justin and I got involved after Patricia Dorn, a well-known Chagas disease researcher in New Orleans, urged Lee to contact the two of us since we had just embarked on a study of kissing bugs around Tucson.

One late June day, we set out to meet for ourselves the residents of Bisbee who had been bitten by these enormous bugs. We passed through Benson, a major stopover for the Butterfield Stage Line in the nineteenth century, traveled on south to Tombstone, made famous by the “Gunfight at the OK Corral”, and into the Mule Mountains surrounding Bisbee. Only occasional cars and pickups were encountered along the two-lane highway. Bisbee looks much as it did during its heyday in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, when it was the greatest metropolis between St. Louis and San Francisco.

The Bugs

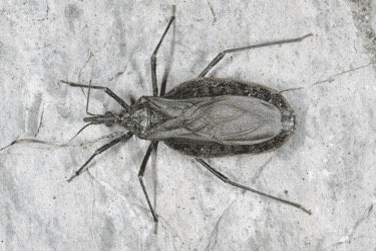

There are ten species of kissing bugs native to the United States, and about 140 species worldwide, almost all residing in the New World. Amongst professional bug collectors like Justin, Triatoma recurva is a “prized catch.” The principal reason is its size (~1.5 inches in adults) and its ability to suck twice its weight in blood (Figure 1). The bug is common in the state of Sonora in Mexico and its breeding range just reaches Arizona. Justin had only sporadically encountered the giant, usually at elevations of 2,000 or above. A gravid female kissing bug flies or walks to a light source such as a porch light and may gain entry to a house beneath door thresholds. She thereafter lays eggs. Nymphs arise from the eggs and shed their chitinous exoskeleton five times as they pass through immature stages to adulthood—reaching the next stage is dependent upon obtaining a vertebrate blood meal.

Collectively known as conenose bugs, Texas bed bugs, and Hualapai tigers, kissing bugs belong to the Reduviidae family of predatory bugs. They specialize in sucking blood from vertebrates instead of feeding on other insects. Therein lies their importance to man: by feeding upon humans, they can serve as vectors of Chagas disease. This disease is caused by a single-celled blood parasite, Trypanosoma cruzi, which infects rodents, domesticated animals, pets, and millions of humans over a large area of Central and South America and Mexico. Because of immigration, the disease is now global in distribution. This parasite may have caused Charles Darwin’s chronic poor health after returning from his voyage on H.M.S. Beagle (1831-1836).

In the United States the parasite is common in wild mammals, especially small rodents, as far north as Oklahoma and Kansas in the Midwest, Utah in the West, throughout California, and as far east as Delaware. Infected bugs carry the parasite in the distal part of their gastrointestinal tract and upon defecation the parasite is transmitted to victims by fecal contamination of bite wounds or by accidental ingestion in food or drink. Many of the animals whose burrows harbor these bugs acquire the infection by ingesting them.

In parts of Latin America where Chagas in humans is common, some kissing bug species are “domesticated,” implying that they live out their life cycle in the houses of human hosts. These nocturnal predators hide in the cracks of the building during the day and forage at night, sensing the proximity of a blood meal by the presence of carbon dioxide and other odors given off by the slumbering host.

The Domiciles of Zacatecas

We met Lee at a bakery at the mouth of Zacatecas Canyon. She greeted us along with John Goerz, who agreed to accompany us through the twelve house sites that lay in this ancient and untouched canyon. Lee handed me a plastic shopping bag with two large yogurt containers. “This is yesterday’s catch from Elizabeth Taylor’s house,” Lee said with a knowing smile. I pried off the lid and found five plump nymphs of Triatoma recurva.

The four of us walked up the incline on coarse blacktop that soon gave way to dust and gravel. We looked up the canyon and could see the home sites, each on rocky outcroppings that provided support for the houses as well as refugia for the small mammals that serve as blood sources for the kissing bugs (Figure 2). Beavertail cactus, desert broom, creosote bush, and scattered juniper covered the canyon walls. Small mammals commonly found in the canyon and potential hosts of T. cruzi are the white-throated wood rat (pack rat), kangaroo rat, desert cottontail, western spotted skunk, ringtail, and rock squirrel. Among larger animals, coyote, collared peccary, mule deer, coatimundi, and bobcat are commonly seen.

The Human Victims

Gerry Dowd’s home, like most in Zacatecas Canyon, was built at the turn of the nineteenth century. It consisted of a wood frame placed directly on granite. There were at least four levels to the house. He has lived with his wife in the canyon for over twenty years. When we entered his bedroom, he said, “We’ll find them here on the walls. Sometimes when I’m reading a kissing bug will crawl up to me to feed.” Like many of the inhabitants of Zacatecas Canyon, Gerry and his wife sleep under mosquito netting to reduce the chances of being bitten. Contrary to their name, kissing bugs do not have a predilection for lips but will bite any exposed area.

Even after multiple bites in the same year, homeowners usually experience only swelling at the site of the bite and localized itching. For most people the bite is harmless, but for those that are sensitized it can cause a life-threatening anaphylactic reaction. One forty-five-year-old woman we interviewed had four severe reactions to the bite. She found the insect in bed each time. She never felt the bite, but noticed her heart rate increasing, felt hot, and twice she lost consciousness and suffered a seizure. Lee gives me the name of a former resident of Zacatecas Canyon, a geologist, who moved to Tucson to get away from the bugs after experiencing several episodes of anaphylaxis after a bite. In the coming years we were to hear of others who moved around the Southwest to escape kissing bugs.

Anaphylaxis is a severe allergic reaction to foreign protein in the bug’s saliva and can be fatal. Ironically, anaphylaxis and severe allergic reactions are the most important health hazard of kissing bugs in the United States, much more important than Chagas disease, which garners all the attention.

We walked to the end of the canyon, visiting several homes where residents have kissing bug problems. All the canyon residents were knowledgeable about kissing bugs and have been bitten many times. One home seemed ideal as a kissing bug habitat—a wood frame house on a rock outcropping with the added enticement of a chicken coop directly behind the owner’s bedroom. Kissing bugs are fond of feeding on chickens, yet chickens are immune to acquiring Chagas—perhaps their body temperature is too high. Another home in the canyon had a large dovecote with breeding ring-necked doves, likely tasty hosts for the bugs. However, the number of pets and farm animals in Zacatecas Canyon has declined over the years; no one keeps donkeys or horses anymore.

John showed us his home, which was the most rustic. We were careful walking up the trail because of rattlesnakes. It was one of the earliest buildings in the canyon. The evening before, he had been reading in an easy chair and found a large kissing bug preparing to suck blood from his abdomen. His mosquito netting was peppered with spots of blood from squashed bugs discovered under the netting.

We ended our canyon walkabout at the home of Elizabeth Taylor, a long-term resident of the canyon. Ms. Taylor authored the Maggie Elliott murder mysteries, The Cable Car Murder and Murder at Vassar, and is a former social worker. She showed us the mosquito netting draped over her bed (Figure 3) and then stepped outside to show us her kissing bug catch from that morning. I could hear scraping in the plastic yogurt container, full of adult and nymph Hualapai tigers. As we left for the car, Justin captured two adult kissing bugs striding boldly across our path. We had enough bugs to start a colony of the giant kissing bugs to put alongside the already thriving colonies of other kissing bug species.

Before leaving Bisbee, Justin and I stopped for a coffee. After leaving the Copper Queen Hotel, we asked people we met on the sidewalk about kissing bugs and everyone, without exception, had been bitten. Because of the stealthy and nocturnal habits of these insects, they were more feared than the much more dangerous rattlesnakes and scorpions that abound in the area. We did not suspect it at the time, but the two of us would spend many summer days over the next fifteen years in the copper mining town of Bisbee, attempting to learn something about these giant bugs and their relationship to man.

STEPHEN A. KLOTZ graduated from the University of Kansas School of Medicine in 1974 and trained in Infectious Diseases at University of Texas San Antonio under David Drutz, MD. His clinical work mainly involved HIV patients and his research concerned how Candida albicans adheres to human tissue. This article describes how he and his friend and collaborator, Justin Schmidt, got started on a project involving kissing bugs that continues to this day.

JUSTIN O. SCHMIDT graduated from the University of Georgia Department of Entomology in 1977 under Murray S. Blum, PhD. His PhD research focused on medically important stinging insects and the chemistry of their venoms. He expanded this work to include other medically important insects including kissing bugs and their natural history, behavior, and how the painfulness of insect stings and bites affect human psychology, morbidity, and behavior.

Acknowledgement: This article is dedicated to John H. Klotz, PhD (deceased), brother and friend of the authors, who insisted we write this piece.