Tom Sewe

Nairobi, Kenya

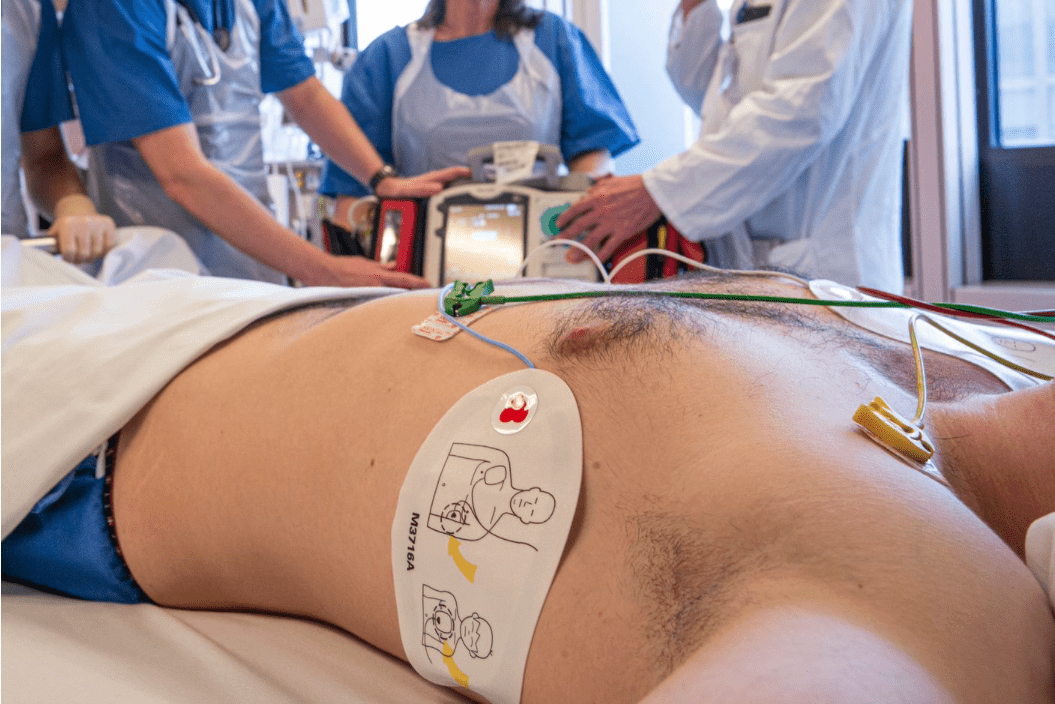

It is a few minutes after 2 AM. A middle-aged woman lays motionless on a table in a hospital emergency department with tubes protruding from multiple orifices. The relentless cardiac monitor screams its flat-line signal as the code-blue team pants, scrubs clinging to their sweaty chests after a phenomenal forty-five-minute cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) attempt. “Time of death, 2:06 AM,” announces the lead doctor. The morgue attendant, as a matter of course, is called. The dejected code-blue team reluctantly disperses to their stations, as a nurse and I remain behind to do the requisite documentation.

Twelve minutes after the declaration of time of death, the endotracheal tube sticking out of the deceased woman’s mouth starts visibly moving. Next, the cardiac monitor beeps with a heart rate. The flat line morphs into a sinus rhythm before our eyes, and the “dead” body’s chest begins to heave with spontaneous respiratory effort. Then she opens her eyes.

This is a true account of a personal experience I had as an emergency department doctor during a night shift at a busy hospital. The patient in question was wheeled to the ICU, where active care resumed and she recuperated before she “truly” died of a massive pulmonary thromboembolism five days later. I had just witnessed my first case of the Lazarus phenomenon.

The Lazarus phenomenon is described as “delayed return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) after cessation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).”1 Such patients, who appear clinically dead, return from the brink of death long after a failed CPR, doing so spontaneously and unassisted. Making its maiden appearance in medical journals in 1982, the coinage of the term has its origins in the Christian gospel account of Lazarus of Bethany, who was miraculously brought back to life by Jesus Christ four days after his death.

Though many theories abound, the precise mechanism of the Lazarus phenomenon remains a mystery. Among leading conjectures is the theory of dynamic hyperinflation, which postulates that rapid ventilation without allowing for adequate exhalation during CPR can lead to hyperinflated lungs. This pulmonary “air-lock” eventually impedes venous return, leading to low cardiac output and potentially a cardiac arrest, causing apparent clinical death.2

Others theorize that the action of drugs such as adrenaline administered via peripheral intravenous cannulae during CPR may be delayed because of a compromised venous return. When venous return is eventually restored after cessation of the dynamic hyperinflation, a belated delivery of drugs could occasion a return of spontaneous circulation.3

Whichever theory holds, it is important to reiterate that in the Lazarus phenomenon, the patient never really died, even though most of them eventually succumb days later. Serious ethical questions arise: was the death a direct result of premature cessation of resuscitative efforts? Was the CPR conducted professionally? Why was it stopped? Would the patient be alive if resuscitation had been continued?

This might explain the reason why cases of autoresuscitation are rarely reported. One case study found that only thirty-two incidences were reported between 1982 and 2008, even though a 2013 study indicated that nearly half of the thousands of French emergency room physicians claimed to have seen a case of autoresuscitation during their career.4 Could doctors be underreporting because of the embarrassing professional and medico-legal consequences associated with a premature declaration of death?

The professional expertise of a doctor who erroneously certified the death might be questioned and lead to disrepute among fellow colleagues. The medical team involved might be accused of negligence and incompetence if a patient “dies a second time” under their care. Lawsuits might arise if doctors are accused of culpable homicide. Hefty damages might be payable if the Lazarus patient survives with a severe disability.

In April 2014, a news article reported that the family of an eighty-year-old grandmother filed a medical malpractice suit, claiming she had been zipped up in a body bag—alive—and put in a hospital morgue’s freezer where she froze to death.5

“In the same year,” reported the same article, “a New York Hospital came under fire after incorrectly declaring a woman as brain dead following a drug overdose. The woman awoke shortly after being taken to the operating room for organ harvesting.”6

Because delayed ROSC occurred within ten minutes in most cases, some authorities recommend that death should not be certified immediately after stopping CPR, and that patients should be passively monitored for at least ten minutes to verify and confirm the death beyond doubt.7

Organ donation, however, presents a new conundrum. Waiting for ten minutes to ascertain whether ROSC might occur could be deleterious. Organ procurement guidelines suggest between two to five minutes of observation after cessation of cardio-pulmonary activity before declaring death.8 Prolonged deprivation of blood flow to the organs inadvertently renders them unsuitable for donation.

At this point, it must be emphasized that death is not an event, but a process. Cessation of circulation and respiration, which are universal conventions for certification of death, are not definitive criteria for death themselves. Since the loss of these critical functions are reversible, it is quite possible to prematurely declare death in the intervening period between such cessation and the actual death, where the integrated function of all organ systems is disconnected.

Speaking of disconnected organ systems, it is said that if a man is decapitated cleanly, the head lives on transiently with observable signs of awareness before it fades into blessed oblivion. From this viewpoint, one is moved to question whether the body is beheaded, or whether indeed the head is decorporated. The eyes may blink or the face may form grimaces. Even “angel lust,” a terminal post-mortem erection, has been observed in the corpses of men who have been executed, particularly by hanging. Whether these apocryphal observations are connected with conscious or unconscious activity is a subject for further research.

In a historical French anecdote, “debate on the subject raged ever since Charlotte Corday—the assassin of Jean-Paul Marat—was guillotined in 1793. The executioner’s assistant, Francois le Gros, lifted her head by the hair, and slapped it on both cheeks. Eyewitnesses reported that the face took on an angry expression, and the cheeks visibly flushed.”9

Such curiosity about the thin line between life and death led to the official commissioning of a French doctor, Dr. Beaurieux, to investigate the severed head of a criminal called Languille, immediately after guillotining. He wrote:

“Here is what I was able to note immediately after the decapitation: […] I called in a strong, sharp, voice: ‘Languille!’ I then saw the eyelids slowly lift up, without any spasmodic contraction […] Next, Languille’s eyes very definitely fixed themselves on mine and the pupils focused themselves. I was not, then, dealing with a vague dull look, without any expression that can be observed any day in dying people to whom one speaks: I was dealing with undeniably living eyes which were looking at me.”10

Stories of “locked-in syndrome” and curious cases of people being buried alive has caused much apprehension in general society. Taphophobia—the fear of being buried alive—was so prevalent in the past that a Society for the Prevention of Burial Before Death was instituted. In recognition of the challenges in determining death, “many people specified in their wills that tests must be carried out to confirm their death, such as pouring hot liquids on the skin, touching the skin with red-hot irons, or making surgical incisions prior to the burial.”11 A coffin was even “invented and patented in 1897 to allow a person accidentally buried alive to summon help through a system of flags and bells.”12

Some research has emerged about a “Lazarus pill.” One study reported the case of a patient in a persistent vegetative state who showed a brief but almost miraculous neurological response to zolpidem, a medication used for sleep. Around 5% of patients with brain damage exhibited spontaneous movement, speech improvement, and occasionally reversal of vegetative state after administration of zolpidem. The physiological mechanism behind these positive effects are poorly understood, and mysteriously disappear as soon as the drug wears off.13 Still, humanity arises from the ashes and trudges on in the tireless transhumanist quest to transcend death.

References

1-3, 11-13. Vedamurthy Adhiyaman, Sonja Adhiyaman, Radha Sundaram “The Lazarus phenomenon” J R Soc Med. 2007 Dec; 100(12): 552–557. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.100.12.552 PMCID: PMC2121643

4. Adam Hoffman, “The Lazarus Phenomenon, Explained: Why Sometimes, the Deceased Are Not Dead, Yet” smithsonianmag.com, March 31, 2016 https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/lazarus-phenomenon-explained-why-sometimes-deceased-are-not-dead-yet-180958613/

5-8. Honor Whiteman, “The Lazarus phenomenon: When the ‘dead’ come back to life” Medical News Today, May 26, 2017 https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/317645#Mistaking-the-living-for-the-dead

9-10. Garrick Alder, “Notes and Queries” The Body Beautiful https://www.theguardian.com/notesandqueries/query/0,5753,-8010,00.html

TOM SEWE, MD, MScFM, MRCGP [INT], is a medical doctor and clinical researcher. He has been living and working in Nairobi, Kenya since 2011. He specializes in Family Medicine, with training from the University of Nicosia, Cyprus. A former graduate of the Creative Writing program at the Wesleyan University in Connecticut, USA, he is also a published novelist (debut novel: A Blood Odyssey) and an essayist. His hobbies include traveling, playing the violin, and listening to opera music.

Leave a Reply